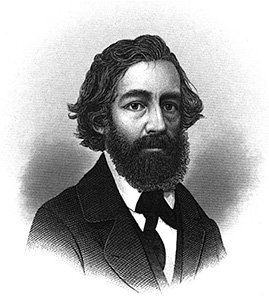

the wittiest book auctioneer of his day in New York

--Evert A. Duyckinck on John Keese

Only a year before his death, Evert A. Duyckinck wrote a marvelous tribute to New York publisher, editor, and auctioneer-punster John Keese (1805-1856) titled "Keese-ana," published in

The Magazine of American History Volume 1 for August 1877. Duyckink's piece was supplemented in the

December 1877 issue by Keese's son, William Linn Keese.

On March 30, 1837 John Keese served as toast-master at the grand inaugural Bookseller's Dinner or "Festival" in New York City, honoring distinguished authors and, more generally, everybody who was anybody in the book trade. Publisher George Dearborn performed the duties of master of ceremonies. So then, Dearborn and Keese, two anthologists and early publishers of Clement C. Moore's "A Visit from St. Nicholas" officiated at the 1837 Bookseller's Festival. Also in attendance: Moore's close friends Charles King, Philip Hone, and John W. Francis--all of whom gave speeches before some 300 assembled guests. Irving, Paulding, Bryant, and Halleck were all there, along with other luminaries including Chancellor Kent, Albert Gallatin, Colonel John Trumbull, Columbia president William Alexander Duer and the professors of Columbia College. Here the enterprising co-host George Palmer Putnam first met Washington Irving, who glorified Halleck and warmly toasted:

"Samuel Rogers—The friend of American genius." --The American Monthly Magazine

Willis mailed in his pro-copyright toast to "The Republic of Letters—in which all who speak the same language are compatriots, and should reciprocate protection and kind feeling." Edgar A. Poe raised his glass to his closest colleagues: "The Monthlies of Gotham—Their distinguished Editors, and their vigorous Collaborateurs."

In his opening address, reprinted in the

Evening Post and other New York newspapers, John Keese acknowledged substantial contributions by the book trade in the past, and challenged publishers to do even more for the cause of American letters:

"We desire still further to explore the mind where mental ore lies buried, to awaken slumbering genius, and to call into active exercise the dormant energy and shrinking talent of our young and much-loved land. Why sleeps the Muse of Drake's twin-brother bard? Why comes not he forth with fairy wand to silence the scribblers of the day? Who among us would not esteem it a high honor to be his publisher, and to issue his beautiful creations in a guise as beautiful as the taste of our best artisans can exhibit ?"

--John Keese, Wit and Littérateur

A few years later, Keese seemed to answer his own challenge by publishing the two-volume set,

The Poets of America: Illustrated by One of Her Painters (1840-1842). However, the first volume would offer only the usual selections by Fitz-Greene Halleck ("Drake's twin-brother bard"): a lyric from "Fanny," "Alnwick Castle" and "Marco Bozzaris."

A Visit from St. Nicholas also would grace Volume 1, attributed to "C. C. Moore" and illustrated with one drawing of St. Nicholas by another guest at the 1837 Bookseller's Dinner, John Gadsby Chapman. Another celebrity artist in attendance was

Robert Walter Weir, who had just finished his own painting of St. Nicholas. The month before the Bookseller's Festival, Weir had offered his freshly painted St. Nicholas to Gulian Verplanck, rating it as "one of the best things I have done" (quoted in Lauretta Dimmick,

Robert Weir's Saint Nicholas: A Knickerbocker Icon).

Keese recycled his 1837 speech at the

1850 Printer's Banquet and (probably) on similar occasions.

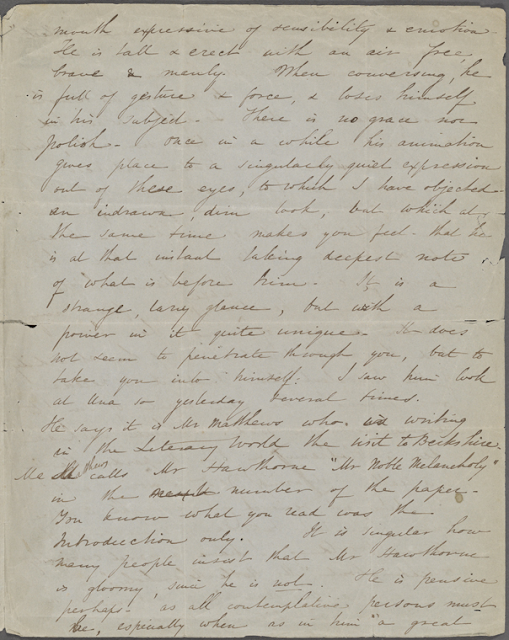

John Keese's son remembered Henry T. Tuckerman and Charles Fenno Hoffman as frequent visitors to their home "on the north side of Atlantic street." Like Duyckinck, Hoffman and Tuckerman later became good friends with Herman Melville.

"within the walls of that house, that evening and on many which followed, with and without the presence of the writer [Henry Morford], was gathered a literary circle which has rarely been equaled in America in numbers, and which has scarcely ever had its superior in the quality of persons composing it…" --John Keese, Wit and Littérateur

Other members of Keese's literary circle around 1839-40 according to Henry Morford were Seba Smith and his wife Elizabeth Oakes Smith, Robert Balmanno and Mary Balmanno, Frances Sargent Osgood, Emma C. Embury, William Gilmore Simms, Rufus Wilmot Griswold, William H. C. Hosmer, Richard Grant White, and Nathaniel Parker Willis.

Considering Keese's intimacy with Duyckinck, Hoffman, and Tuckerman, Melville had to know

of him. As Luther Stearns Mansfield notes in

Melville's Comic Articles on Zachary Taylor, Duyckinck named John Keese among other occasional contributors to

Yankee Doodle. The most likely time for Melville and Keese to have met or socialized would have been in New York City between say 1847 and 1850, before Melville moved himself and family to Berkshire County, Massachusetts.

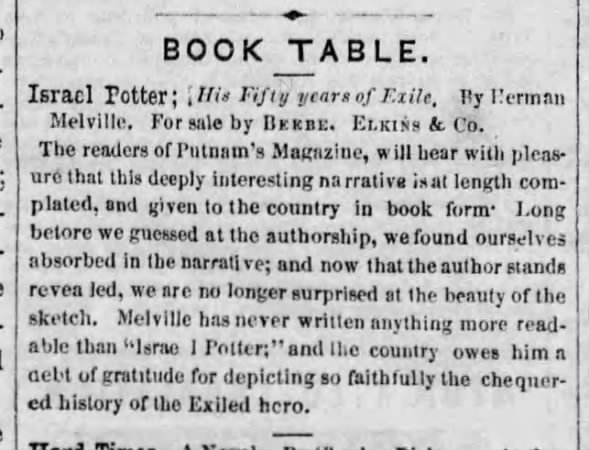

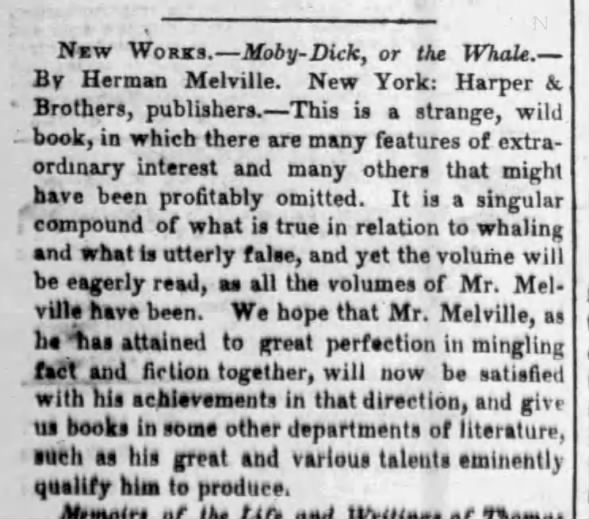

Found on Newspapers.com powered by Newspapers.com

Here's a sample of John Keese at work, from Evert Duyckinck's 1877 memorial:

His deprecatory remark on the sacrifice of a copy of Bacon's Essays for twelve and a half cents was pathetic. “Really, that is too much pork for a shilling!" Selling, one evening, a book on German politics by Goetz, he hesitated over the catalogue, as if at the delicacy of the author’s name. “What is it?" asked one of the audience. “ Oh! something, I suppose, on the internal difficulties of the country." In a similar vein was his introduction of Gutzslaff's China with the observation, “This was the gentleman with a commotion in his bowels."

Sometimes his wit would be more pointed. “This," said he, holding up a volume of verse of a well known type, “is a book, by a poor and pious girl, of poor and pious poems." There was a heavy remainder of a certain volume, the “ Lives of the Shoemakers," which required all his ingenuity to dispose of. He would bring out a copy with the unfailing introduction, “This is the last copy. The book was awl the author wrote and was awl that his widow inherited from him, her sole reliance"—a jest which may have been stimulated by Shakespeare’s cobbler in Julius Caesar. Of some heavy folio, dragging at a feeble price, he would end his efforts—“ Going—going—cheap for a back-log!" Knocking down a “ Hand-book," he added, for the comfort of the purchaser, “You will see that it is pretty well fingered." “Damaged, you say, yes—a little wet on the outside—but you will find it dry enough within." On another occasion he parried this word "damaged" quite happily. A young son of a highly respectable Episcopal clergyman of this city, was a privileged attendant at the auction room. Keese offered a soiled or injured copy of the “Book of Common Prayer." “ Isn’t it damaged," exclaimed the youth; upon which Keese turned round to him slowly, and fixing his attention upon him with great gravity, in a tone of soberness and solemnity, addressed him, “ Has your father taught you to regard that as a damaged book ?"

--Keese-ana by Evert A. Duyckinck