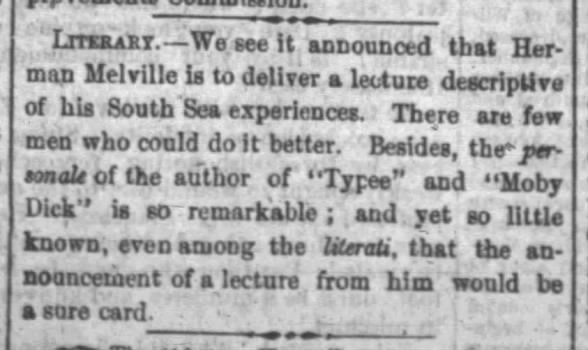

From the Brooklyn Daily Times, September 21, 1858; found at Newspapers.com among items "Added in the past 1 month":

LITERARY.-- We see it announced that Herman Melville is to deliver a lecture descriptive of his South Sea experiences. There are few men who could do it better. Besides, the personale of the author of "Typee" and "Moby Dick" is so remarkable; and yet so little known, even among the literati, that the announcement of a lecture from him would be a sure card.A Brooklyn journalist thinks Melville a "remarkable" looking person, and along with Typee (1846) remembers Moby-Dick (1851) instead of a more recent work like Israel Potter (1855) or The Piazza Tales (1856) or The Confidence-Man (1857).

Here the italicized word personale refers I guess to personal appearance and manner, to bodily attributes expressive of one's individual personality. So New York literati might know a great deal about Melville's literary personae (Tommo and Ishmael, for example), without having seen the writer himself, up close and in person.

The association of Melville with Moby-Dick, and the focus on his physical appearance apart from his reputation among the literati, are original and distinctive elements, added to the received announcement of Melville's determination to lecture on his South Sea adventures. The Brooklyn journalist (Call him Walt?) was commenting on some version of this item:

|

| Troy Daily Times (Troy, NY) - September 21, 1858 via Fulton History |

"Herman Melville has prepared a lecture descriptive of his adventures in the South Sea, which he intends to deliver this winter."The Brooklyn Daily Times was then published by owner and founder George C. Bennett. I don't know if Walt Whitman wrote the 1858 Melville notice, but it coincides nicely with the period in which Whitman

"returned to full-time editing in 1857 for the Brooklyn Daily Times, after an interim of nine years." --Walt Whitman: An Encyclopedia, ed. J. R. LeMaster and Donald D. Kummings (Routledge, 1998), page 81.Tenure confirmed by Douglas A. Noverr in "Journalism," A Companion to Walt Whitman, ed. Donald D. Kummings (Wiley-Blackwell, 2009), page 36:

"Whitman's last significant connection with a Brooklyn newspaper was with the Daily Times in the period of early 1857 until the spring of 1859."The phrase "sure card" appears in Brooklyniana, No. 8, unsigned but attributed to Walt Whitman:

"These circus exhibitions, by the way, have always been a sure card in Brooklyn."

Whitman, Walt [unsigned]. "Brooklyniana, No. 8." Brooklyn Standard, 25 January 1862. The Walt Whitman Archive. Gen. ed. Ed Folsom and Kenneth M. Price. Accessed 25 May 2019. <http://www.whitmanarchive.org>.

| Leaves of Grass - Boston, 1860 |

To a Pupil.

1. IS reform needed? Is it through you?The greater the reform needed, the greater the PER-

SONALITY you need to accomplish it.

2. You! do you not see how it would serve to have eyes,

blood, complexion, clean and sweet?Do you not see how it would serve to have such a

body and Soul, that when you enter the crowd,

an atmosphere of desire and command enters

with you, and every one is impressed with your

personality?

3. O the magnet! the flesh over and over!Go, mon cher! if need be, give up all else, and com-

mence to-day to inure yourself to pluck, reality,

self-esteem, definiteness, elevatedness,Rest not, till you rivet and publish yourself of your

own personality.

Whitman, Walt. "To a Pupil." Leaves of Grass. 1860. The Walt Whitman Archive. Gen. ed. Ed Folsom and Kenneth M. Price. Accessed 25 May 2019. <http://www.whitmanarchive.org>