Wednesday, June 30, 2021

Herman Melville

Wednesday, June 23, 2021

Forced to fly: Dryden's hind and Melville's doe

The principal character is that of the captain, an old weather-beaten whaler. The points in his peculiar disposition are strongly painted. He is afflicted with a species of monomania, and having lost one of his legs in a conflict with a white whale of enormous size and tremendous power, he registers a vow of vengeance against this particular fish, which thus

“Was doomed to death, but fated not to die.”

In the pursuit of this absurd species of vengeance, the captain, Ahab, at length meets with his old antagonist, well known from its having “a milky white head and hump, all crows feet and wrinkles, and harpoons sticking in near his starboard fin.” He encounters this formidable enemy, and loses his life in the attack, and the whale, after staving in the bows of the ship, escapes, leaving the vessel to founder at sea with all hands.

Like Dryden's allegorical deer, Melville's immortal monster of a whale "Was doomed to death, but [though] fated not to die." For context, here is the longer passage via Bartleby.com:

A MILK-WHITE Hind, immortal and unchanged,

Fed on the lawns and in the forest ranged;

Without unspotted, innocent within,

She feared no danger, for she knew no sin.

Yet had she oft been chased with horns and hounds,

And Scythian shafts, and many wingèd wounds

Aimed at her heart; was often forced to fly,And doomed to death, though fated not to die.

Dryden's fable of true faith, all three parts of it, graced the compendium of Select British Poets, Or, New Elegant Extracts from Chaucer to the Present, edited by William Hazlitt (London, 1824).

As shown previously on Melvilliana, the 1837 Catalogue of Books in the Library of the Young Men's Association of the City of Albany listed "Hazlett's Select British Poets" on page 14, under "H." Hazlitt's 1824 volume supplemented the works of older poets like Dryden with new "extracts" by contemporary Romantic poets. This edition of Hazlitt's Select British Poets was available in Albany, New York bookstores by late 1826, four years before Herman Melville moved there from New York City with his family. In 1835-7 Melville belonged to the Albany Young Men's Association where Hazlitt's anthology was available in the library along with two different sets of "British Poets," numbered 1112 (12 vols.) and 1390 (11 vols.) in the 1837 Catalogue. The 1828 Catalogue of Books in the Albany Library lists a four-volume set of "Dryden's Poems" in addition to "Dryden's Virgil" in three volumes.

Dryden's "immortal" white doe ("She") represents the Roman Catholic Church; the panther stands for the protestant Church of England. That alliterative phrase "forced to fly" (or "forc'd to fly" in early versions) verbally links Dryden's doe to Melville's in the 1850 review essay Hawthorne and His Mosses. There Melville famously painted Truth as a shy white doe, sacred or just scared.

For in this world of lies, Truth is forced to fly like a scared white doe in the woodlands ; and only by cunning glimpses will she reveal herself, as in Shakspeare and other masters of the great Art of Telling the Truth, — even though it be covertly and by snatches.

-- "Hawthorne and His Mosses," Literary World vol. 7 - August 17, 1850 page 126.

Justifying his emendation to "sacred white doe," Hershel Parker cites Dryden's poem along with Wordsworth's White Doe of Rylstone as influential analogues:

Mrs. Melville wrote "scared." In Herman Melville: A Biography (1.756) Parker introduced the emendation of "sacred white doe" instead of "scared white doe" on the analogy of John Dryden's "milk-white Hind" in "The Hind and the Panther" (1687) and William Wordsworth's "White Doe of Rylstone" (1807).... --Third Norton Critical Edition of Moby-Dick, edited by Hershel Parker (W. W. Norton & Company, 2018) page 551 note 9.

In the same footnote Parker calls attention to the manuscript correction of "Truth is found," as the scribe Melville's wife Elizabeth Melville first wrote, to "Truth is forced." Let's look now since images of the manuscript version in Mrs. Melville's hand, mostly, are so easy to access courtesy of NYPL Digital Collections.

Manuscripts and Archives Division, The New York Public Library. "“Hawthorne and his mosses”" The New York Public Library Digital Collections. 1850. https://digitalcollections.nypl.org/items/23ebb010-184f-0133-f66c-58d385a7bbd0

Sure enough there's found, canceled and replaced by "forced" to give the correct reading

forced to fly.

In a wicked world, Melville's Truth-doe is "forced to fly" like Dryden's Church of Rome, allegorized as a hunted white hind or female deer. The glimpse of Dryden's sacred white doe in the Morning Herald shows that one London reviewer recognized Melville's white whale as equally elusive and immortal.

Related posts:

- London Morning Herald notices of The Whale

https://melvilliana.blogspot.com/2021/06/london-morning-herald-notices-of-whale.html

- Sacred White Deer in and around Pittsfield

https://melvilliana.blogspot.com/2015/04/sacred-white-deer-in-and-around.html

- Legend of the White Deer

https://melvilliana.blogspot.com/2015/04/lengend-of-white-deer-in-godfrey.html

Tuesday, June 22, 2021

Hot Off The Press – New Titles This Week

London Morning Herald notices of The Whale

New items transcribed below include an earlier printing of the long-undiscovered paragraph that also appeared in the London Globe and Traveller, known for half a century only by a blurb ascribed in publisher's ads to an otherwise unidentified "Evening Paper." Another new item is the review of The Whale on November 17, 1851, not collected in Herman Melville: The Contemporary Reviews, edited by Brian Higgins and Hershel Parker (Cambridge University Press, 1995; paperback 2009). The likely existence of this later and longer review in the Morning Herald was demonstrated in two previous posts on Melvilliana:

- Looking for another Whale review in the London Morning Herald

https://melvilliana.blogspot.com/2020/02/looking-for-another-whale-review-in.html

- More evidence for another London Morning Herald review of THE WHALE

https://melvilliana.blogspot.com/2020/03/more-evidence-for-another-london.html

All honour and praise to Fenimore Cooper, whose memory will never be suffered to die whilst the English language endures. That great and lamented genius was one of the most forcible delineators of sea-life that ever made old ocean and his familiars his peculiar study. But he has left a worthy successor (we know how much we say when we assert this) in the person of Herman Melville, whose new work, "The Whale," is perhaps the raciest thing of the kind that was ever produced. Melville does not merely skim the surface, he dives into the deep unfathomed main. We smell and taste the brine in every page. His ink must be the black liquor of the cuttle-fish, and his pen drawn from the wing of the albatross. "The Whale" is a very great performance. --London Morning Herald, 17 October 1851.

HERMAN MELVILLE is on the right track now. His “Omoo,” “Typee,” and “White-jacket,” gave evidence of great and peculiar powers; but the audacity of youthful genius impelled him to throw off these performances with “a too much vigour,” as Dryden has it, which sometimes goes near to defeat its own end. But in “The Whale,” his new work, just published, we see a concentration of the whole powers of the man. Resolutely discarding all that does not bear directly on the matter in hand, he has succeeded in painting such a picture—now lurid, now a blaze with splendour—of sea life, in its most arduous and exciting form, as for vigour, originality, and interest, has never been surpassed.From the London Morning Herald, October 27, 1851; excerpted from the London Morning Advertiser review on October 24, 1851:

“THE WHALE.” —Of this new work, by the very popular author of “Typee” and “Omoo,” the Morning Advertiser says,— "To convey an adequate idea of a book of such various merits as that which Mr. Melville has here placed before the reading public is impossible in the scope of a review. High philosophy, liberal feeling, abstruse metaphysics popularly phrased, soaring speculation, a style as many-coloured as the theme, yet always good and often admirable; fertile fancy, ingenious construction, playful learning, and an unusual power of enchaining the interest and rising to the verge of the sublime—all these are possessed by Herman Melville, and exemplified in his new work. As a sample of Herman Melville’s learning, we may refer to the chapter headed ‘Cetology,’ in the second volume; and that we have not over-rated his dramatic ability for producing a prose poem, read the chapter on the ‘Whiteness of the whale,’ and the scene where Ahab nails the doubloon to the mast, as an earnest of the reward he will give to the seaman who first ‘sights’ ‘Moby Dick,’ the white whale, the object of his burning and unappeasable revenge Then come whale adventures wild as dreams, and powerful in their cumulated horrors. Now we have a Carlylism of phrase, then a quaintness reminding us of Sir Thomas Browne, and anon a heap of curious out-of-the-way learning, after the fashion of the Burton who ‘anatomised melancholy.’ Mingled with all this are bustle, adventure, battle, and the breeze. In brief, the interest never palls. We can only, in conclusion, refer the reader to these volumes, than which three more honourable to American literature have not yet reflected credit on the country of Washington Irving, Fenimore Cooper, Dana, Sigourney, Bryant, Longfellow, and Prescott.” --London Morning Herald, 27 October 1851.

Next item is from the London Morning Herald of November 3, 1851; reprinted with different punctuation and without credit to the London Morning Post where the same notice had appeared on October 20, 1851, as reported here on Melvilliana:

- Melville is a star

https://melvilliana.blogspot.com/2016/04/melville-is-star-notice-of-whale-in.html

"THE WHALE," by Herman Melville, just published, is perhaps the most extraordinary work that has appeared in England for a very great many years. The novelty of the materials that constitute the interest, the novelty of the manner of dealing with them—the poetical, combined with the practical, nature of the author—the rare power with which he knits us to every character in succession—the wild, impetuous grandeur of his scenes, the impulsive force and vigour of his language—these together make up one of the most fascinating books that was ever read. Captain Ahab is a character which few men could have conceived, and how few could have drawn with such marvellous earnestness and strength; and his pertinacious pursuit of the great white whale (Moby Dick) is executed in the true spirit and with the full force of great original genius. Melville is a star, and of no ordinary magnitude, in the literary firmament. --as reprinted in the London Morning Herald, 3 November 1851.

Transcribed below is the later, longer review of Melville's Whale that appeared in the London Morning Herald on November 17, 1851. I'm adding this also to the tally of favorable reviews in the Melvilliana post

- Moby-Dick widely praised in 1851-2

https://melvilliana.blogspot.com/2020/02/moby-dick-widely-praised-in-1851-2.html

LITERATURE.

BOOKS RECENTLY PUBLISHED.

The Whale. By Herman Melville, Author of “Typee,” &c. Three Vols. Richard Bentley.—

In this novel Mr. Melville has exceeded what he has hitherto written, in all that regards the conception of the plot and the drawing of the characters. The hardships and perils of the whale fishery are delineated with much detail, and all the appearance of rigid truth; indeed it is difficult to conceive that an author could give so minute and exact a description of this hazardous calling unless he had acted a part in the scenes he so vividly paints. To constitute a novel, a connected plot, contrast of character, and situations more or less striking are required, and, though it must be allowed that the greater portion of these volumes is occupied with didactic and scientific matter, yet this is so interwoven with a romantic story that all readers are likely to take a strong interest in it. The principal character is that of the captain, an old weather-beaten whaler. The points in his peculiar disposition are strongly painted. He is afflicted with a species of monomania, and having lost one of his legs in a conflict with a white whale of enormous size and tremendous power, he registers a vow of vengeance against this particular fish, which thus

“Was doomed to death, but fated not to die.”

In the pursuit of this absurd species of vengeance, the captain, Ahab, at length meets with his old antagonist, well known from its having “a milky white head and hump, all crows feet and wrinkles, and harpoons sticking in near his starboard fin.” He encounters this formidable enemy, and loses his life in the attack, and the whale, after staving in the bows of the ship, escapes, leaving the vessel to founder at sea with all hands.

Such is a rough outline of the main incident of this remarkable novel, which, though based on an improbability, is nevertheless read with great delight. There is a certain wild grandeur in the arrangements of the actors and accessories, a great vigour in the delineation of character, and the language throughout is forcible, though sometimes a little inflated, and sometimes descending rather too much into technicality. There are several animated descriptions, among which may be particularly mentioned the accounts of New Bedford and Nantucket, the shipping of the hands on board the Pelog, several engagements with the whales, and an amazingly effective scene of a storm at sea with lightning. The novel is unquestionably the production of no ordinary mind.

--London Morning Herald, 17 November 1851; digitized in June 2021 and accessible on The British Newspaper Archive. https://www.britishnewspaperarchive.co.uk/

Related post:

- London Morning Herald notice, White-Jacket

https://melvilliana.blogspot.com/2021/06/london-morning-herald-notice-white.html

Monday, June 21, 2021

London Morning Herald notice, White-Jacket

From the London Morning Herald of March 4, 1850; now accessible on The British Newspaper Archive with pages recently digitized in this very month of June 2021.

LITERATURE.

BOOKS RECENTLY PUBLISHED.

...

White Jacket; or, The World in a Man of War. By Herman Melville, Author of “Redburn,” “Typee,” &c. Two Vols. R. Bentley.— A cruise in an American man of war is the subject of this novel, which conveys a lively and, no doubt, accurate description of the mode of life on board vessels of that class. The author served as a common sailor in the American navy for more than a year, and his reflections arising from personal experience are incorporated in these volumes. He offers many suggestions for improving the internal economy of vessels of war and for bettering the condition of the sailor, without impairing the efficiency of the service. He expatiates particularly on the subject of flogging in the navy, which he conceives might be much abated, if not altogether relinquished. The novel is very entertaining, and full of such information as could only be afforded by one who has served before the mast.

--London Morning Herald, 4 March 1850.

- London Morning Herald notices of The Whale

https://melvilliana.blogspot.com/2021/06/london-morning-herald-notices-of-whale.html

Saturday, June 19, 2021

Tuesday, June 15, 2021

Racy and entertaining

THE MESSRS HARPER promise us on Saturday the new work by Melville, author of "Typee" and Omoo." It is entitled "Mardi; and a Voyage Thither." Melville has already eclipsed De Foe in his racy and entertaining productions. His new book will have a great sale." -- Boston Daily Evening Transcript, April 11, 1849

Both volumes of the first American edition (New York: Harper & Brothers, 1849) of Herman Melville's Mardi: and a Voyage Thither have been digitized by the great Internet Archive; the physical books are held by the University of Pittsburgh Library.

Sunday, June 13, 2021

Great Lake break

|

| Lake Superior |

"... this Lakeman, in the land-locked heart of our America, had yet been nurtured by all those agrarian freebooting impressions popularly connected with the open ocean. For in their interflowing aggregate, those grand fresh-water seas of ours,—Erie, and Ontario, and Huron, and Superior, and Michigan,—possess an ocean-like expansiveness, with many of the ocean’s noblest traits; with many of its rimmed varieties of races and of climes."

-- Moby-Dick chapter 54, The Town-Ho's Story.

|

| Philadelphia Inquirer - October 25, 1851 via GenealogyBank |

The Town-Ho's Story by Herman Melville was first published in Harper's New Monthly Magazine for October 1851. Reprinted in American newspapers including the St. Louis Missouri Republican on October 12 and 13, 1851; Philadelphia Inquirer on October 25, 27 and 28 1851; and Cincinnati Liberty Hall and Weekly Gazette on December 4 and 11, 1851.

In the Cincinnati Liberty Hall and Weekly Gazette for December 4, 1851, the first installment of "The Town-Ho's Story" was followed by the poem "Pumpkin Pies" By A Vermonter, reprinted there from the New York Tribune (July 8, 1851).

Friday, June 11, 2021

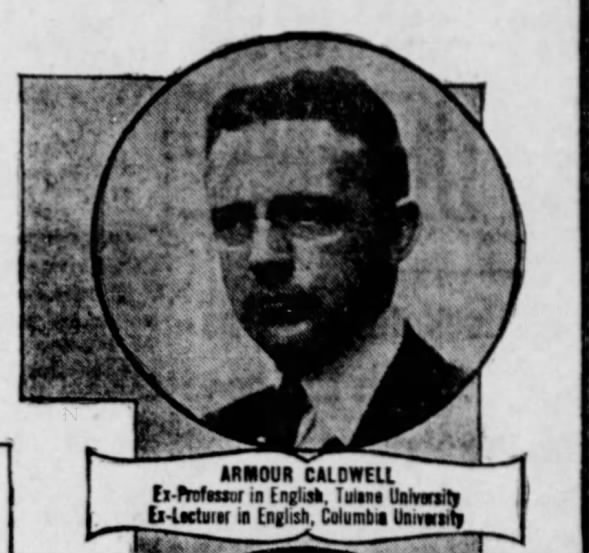

Armour Caldwell at Tulane, 1908

07 Feb 1916, Mon Pittsburgh Daily Post (Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania) Newspapers.com

07 Feb 1916, Mon Pittsburgh Daily Post (Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania) Newspapers.comNew Orleans Origins of Melville Revival: Armour Caldwell at Tulane, 1908

The Best Sea Story Ever Written.Less well known as active Melville advocates are two Massachusetts journalists: Charles Goodrich Whiting (1842-1922), editor of the Springfield Republican; and Philip Hale (1854-1934), the Boston music critic who championed Melville for forty years, thirty in his newspaper column "As the World Wags." In Butte, Montana, ladies of the "Homer Club" reserved a day in early 1907 for "sea tales" as part of their daunting program of literary study. Ethelyn Caldwell Adams (Mrs. John Coit Adams) originally was assigned Moby-Dick, but in February 1907 it was Mrs. L. P. Sanders who "presented a sketch of Melville, the author of 'Moby Dick.'"

03 Feb 1907, Sun The Anaconda Standard (Anaconda, Montana) Newspapers.com

03 Feb 1907, Sun The Anaconda Standard (Anaconda, Montana) Newspapers.comStill we speak of THE Revival, later than and distinct from the Melville "vogue" before the First World War (Zimmerman, page 23). THE Revival launched with the centenary in 1919 and Raymond Weaver's "foolish and enormously influential" biography, as Stanley Edgar Hyman called it. Martina Pfeiler and I will be looking at precursors, each with ties in New York City--predictably, considering the Columbia University connections of so many participants. Less predictably, one flowered in the South.

- Who was Armour Caldwell?

- What did he say about Moby-Dick? and

- What the devil is a picayune? (Answered first, with help from Grammarphobia: Anglicized version of picaillon, south Louisiana French for the Spanish medio real worth 6 1/4 cents, the smallest coin in circulation and the name of the daily newspaper in New Orleans.)

Who was Armour Caldwell?

What did Armour Caldwell say about Moby-Dick?

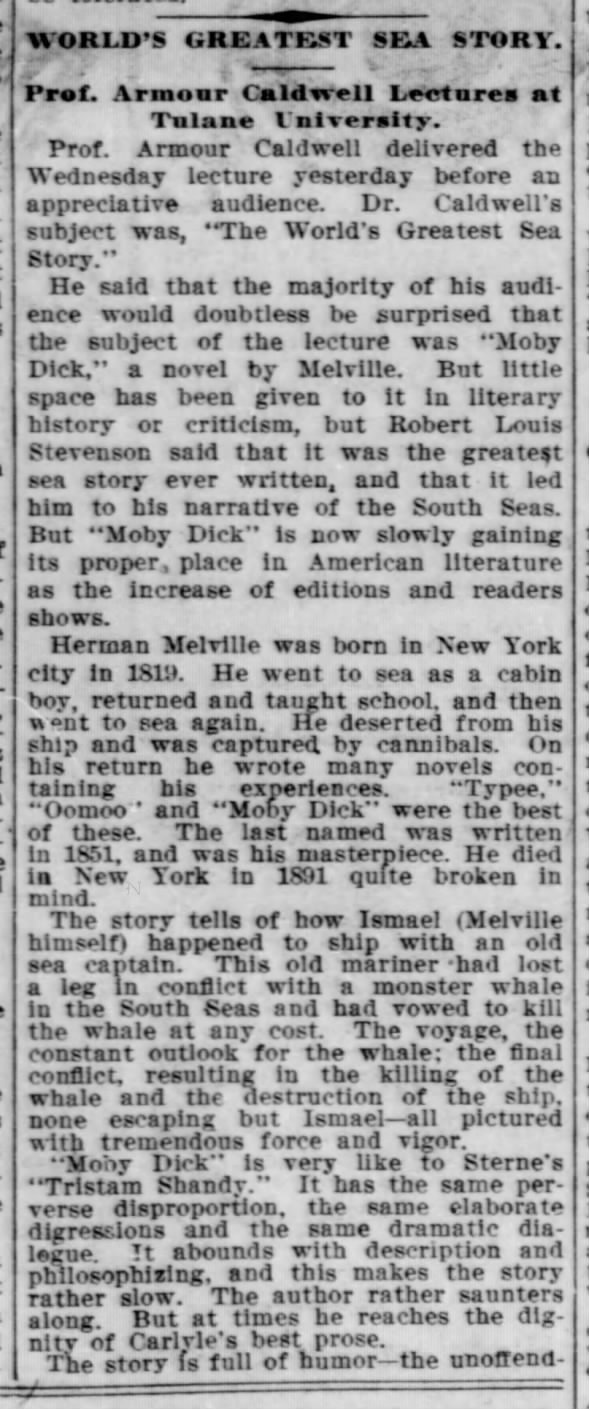

02 Apr 1908, Thu The Times-Democrat (New Orleans, Louisiana) Newspapers.com

02 Apr 1908, Thu The Times-Democrat (New Orleans, Louisiana) Newspapers.com

02 Apr 1908, Thu The Times-Democrat (New Orleans, Louisiana) Newspapers.com

02 Apr 1908, Thu The Times-Democrat (New Orleans, Louisiana) Newspapers.com

To begin with, Caldwell expected his audience to be "surprised" by the subject of his lecture, Moby-Dick, since "little space has been given to it in literary history or criticism." At the same the speaker did register "the increase of editions and readers." New editions then were the illustrated 1902 volume in the series of Famous Novels of the Sea by Charles Scribner's Sons; and the 1907 volume in Everyman's Library, edited by Earnest Rhys. Availability of these new volumes offered some hope that "Moby Dick is now slowly gaining its proper place in American Literature."

The story tells of how Ismael (Melville himself) happened to ship with an old sea captain. This old mariner had lost a leg in conflict with a monster whale in the South Seas and had vowed to kill the whale at any cost. The voyage, the constant outlook for the whale; the final conflict, resulting in the killing of the whale and the destruction of the ship, none escaping but Ismael--all pictured with tremendous force and vigor.

Of the Pequod's crew the newspaper names only Melville's narrator Ishmael ("Ismael"), reporting that Caldwell identified him as a stand-in for "Melville himself." But Caldwell keyed on "the old sea captain" and his inflexible, vengeance-driven quest. Enthralled by the revenge plot, the lecturer in both extant newspaper accounts has Moby Dick killed in the end, making Ahab a kind of Beowulf and the White Whale dead as the Dragon.

"It has the same perverse disproportion, the same elaborate digressions and the same dramatic dialogue. It abounds with description and philosophizing, and this makes the story rather slow."

In 1851, William A. Butler had said much the same thing when reviewing Moby-Dick for the Washington National Intelligencer. With the help of Mary K's black book on Melville's Sources, we can readily find pertinent scholarship through 1987. In the Hendricks House edition of Moby-Dick, Luther S. Mansfield and Howard P. Vincent particularize debts to Tristram Shandy for the cozy "confidential disclosures" between Ishmael and Queequeg as bedmates in Chapter 10 A Bosom Friend; and for the figure of Cervantes in Melville's apostrophe to "thou Just Spirit of Equality" and "great democratic God!" in Chapter 26 Knights and Squires.

After Sterne, Caldwell named Carlyle as a major influence on the elevated style in Moby-Dick which occasionally "reaches the dignity of Carlyle's best prose." Here again later scholarship has abundantly confirmed Melville's debt to Carlyle, which seemed obvious not only to Caldwell but also to the earliest critics of Moby-Dick (and before that, Mardi). Friendly ones regretted Carlyle's bad influence; hostile ones condemned it. Caldwell's Columbia teacher and colleague William P. Trent counted as a knock, Melville's "obvious imitation of Carlylean tricks of style and construction." MacMechan the Carlyle expert never named the author of Sartor Resartus. In the new 20th century, however, imitations of Carlyle sounded fine to Caldwell, another descendant of Scots.

In the Extracts section of Moby-Dick Melville quotes from Goldsmith's History of the Earth and Animated Nature. But Caldwell names Goldsmith as one of Melville's more important influences for his "unoffending humor," not his geology or zoology. The 1906 anthology, English Humorists of the Eighteenth Century, groups Goldsmith with Sterne, Addison, and Steele, providing a handy collection of possible influences on Moby-Dick. For his part, Melville once scorned the sort of imitation that Caldwell alleges: "We want no American Goldsmiths." Ironically, Melville's own debt to Washington Irving's graceful way of travel writing was already manifest to Evert Duyckinck in 1847, as John Bryant points out in Melville and Repose. What Bryant elsewhere calls "the Ishmaelian mode" carries on "the 'amiable tradition' of British humor" and is characterized by "geniality" (1994, Comic Debate, page 1). In contrast to the early recognition of Melville's debts to Carlyle, recognition of the Goldsmith (English or American) in Ishmael is really a 20th century insight.

Caldwell also addressed philosophical and psychological dimensions of Moby-Dick:

"But Melville has a great power of philosophy also. The powerful strokes with which he depicts the gradual decay of the old captain's mental faculties is as subtle a piece of psychological insight as one will find in fiction.... "

-- New Orleans Times-Democrat, April 2, 1908

Caldwell understands Ahab's whale-mania as a variety of progressive mental illness. The lecturer's appreciation of Melville's "psychological insight" anticipates scholarship on Ahab's "madness" or "insanity," hinting perhaps at the clinical focus of more recent work in the genre of disability studies, rather than psychoanalytic readings inspired by Freud and Jung.

|

| New Orleans Daily Picayune - April 2, 1908 - page 5 via Genealogy Bank |

Caldwell ended by quoting a student reader who

"after reading Moby Dick told me that he thought it was a symbol, or had a meaning that it was the story of man's pursuit after his heart's desire, how after a long, hard journey it was only gotten at the end of the voyage, and then both go down together in the awful abyss."

-- Daily Picayune, April 2, 1908

The Picayune reported also that Caldwell "had planned last summer to write Melville's life, but he found some on was already at work on it." It's too bad Caldwell gave up on the idea, since contemplated biographies by J. E. A. Smith, Arthur Stedman, Frank Jewett Mather, and Melville's daughter Elizabeth ("Bessie") never materialized.

Caldwell's Tulane lecture marks the earliest known phase of the specifically academic Melville Revival. Archibald MacMechan had already praised Moby-Dick as "The best sea story ever written." But MacMechan's view of Moby-Dick as best-sea-story-ever did not employ now familiar terms of formal literary analysis. As V. L. O. Chittick points out, "Symbolism, allegory, myth, ritual, and literary sources are not discussed--nor, of course, are fixations, complexes, and compulsions." At Tulane, Armour Caldwell did speak of 18th century literary influences on Moby-Dick, citing Sterne for the technique of narrative expansion through digression and dialogue; and Addison, Steele, and Goldsmith for inoffensive, British-style whimsy. Caldwell explicitly addressed the problem of literary symbolism, sharing the response of a student reader struck by the symbolic meaning of Ahab's quest as "man's pursuit after his heart's desire." And Caldwell did address Melville's treatment of "complexes and compulsions," judging the portrayal of Ahab's monomania to be "as subtle a piece of psychological insight as one will find in fiction." Moby-Dick as a great story is one thing. Moby-Dick as the deserving subject of literary analysis and study is another. At Tulane in 1908 Armour Caldwell bequeathed it to fellow English Majors, for better or worse.

Works Cited

American Leader, volume 1 number 1. February 29, 1912. Photo and bio of Armour Caldwell, Managing Editor on pages 10 and 11.

Aronoff, Eric. "The Melville Revival" in Herman Melville in Context, ed. Kevin J. Hayes (Literature in Context, pages 296-306). Cambridge University Press, 2018. doi:10.1017/9781316755204.030Bercaw, Mary K. Melville's Sources. Northwestern University Press, 1987.Bryant, John. Melville and Repose: The Rhetoric of Humor in the American Renaissance. Oxford University Press, 1993.

Bryant, John. “Melville, Twain and Quixote: Variations on the Comic Debate.” Studies in American Humor, New Series 3 number 1, 1994, pages 1–27. JSTOR, www.jstor.org/stable/42573302.

Chittick, V. L. O. “The Way Back to Melville: Sea-Chart of a Literary Revival.” Southwest Review volume 40 number 3 (Summer 1955) pages 238–248. JSTOR, www.jstor.org/stable/43464100.

Hyman, Stanley Edgar. The Promised End. World Publishing Company, 1963.

Irving, Washington. Washington Irving's Sketch book. With introduction by Brander Matthews and notes by Armour Caldwell. New York: Longman's, Green, and Co., 1905.

MacMechan, Archibald. "The Best Sea Story Ever Written" in Queen's Quarterly volume 7, October 1899, pages 120-130.Marovitz, Sanford E. The Melville Revival chapter 33 in A Companion to Herman Melville, ed. Wyn Kelley. Blackwell, 2006.

Manley, Marian C. A Worm's-Eye View of Library Leaders. Wilson Library Bulletin volume 27 (November 1952) page 233; reprinted in An American Literary History Reader, ed. John David Marshall (Shoe String Press, 1961) pages 150-160 at page 155.

Melville, Herman. Moby-Dick; Or, The Whale. Ed. Luther S. Mansfield and Howard P. Vincent. Hendricks House, 1952.

Pfeiler, Martina. “‘The Time has Come for a Melville Revival’: Edwin Emery Slosson’s Journalistic Contributions to the Origins of Melville’s Revival in New York City.” Conference paper presented June 17, 2019 at the 12th International Melville Society Conference in New York City.Riegel, O. W. “The Anatomy of Melville's Fame.” American Literature volume 3 number 2 (May 1931) pages 195–203. JSTOR, www.jstor.org/stable/2919779.

Trent, William P. A History of American Literature, 1607-1865. New York: D. Appleton, 1903. Pages 389-391 at 390.

Zimmerman, Michael P. "Melville in the 1920's: A Study in the Origins of the Melville Revival, with an Annotated Bibliography." PhD dissertation. Columbia University, 1963.

- Moby-Dick widely praised in 1851-2

https://melvilliana.blogspot.com/2020/02/moby-dick-widely-praised-in-1851-2.html

- Forty years of Philip Hale on Melville

https://melvilliana.blogspot.com/2016/08/forty-years-of-philip-hale-on-melville.html

- Charles Goodrich Whiting

https://melvilliana.blogspot.com/2016/08/charles-goodrich-whiting-author-of.html

Thursday, June 10, 2021

Links to Hawthorne and His Mosses, 1850

- Part 1: Literary World August 17, 1850

https://hdl.handle.net/2027/njp.32101064475088?urlappend=%3Bseq=135

- Part 2: Literary World August 24, 1850

https://hdl.handle.net/2027/njp.32101064475088?urlappend=%3Bseq=151

- Melville's book reviews in manuscript

https://melvilliana.blogspot.com/2017/12/book-reviews-in-manuscript-at-nypl.html

- Charleston reprinting of Hawthorne and His Mosses

https://melvilliana.blogspot.com/2019/05/charleston-reprinting-of-hawthorne-and.html

Saturday, June 5, 2021

Urquhart's Pillars of Hercules, anonymous Literary World review

|

URQUHART'S PILLARS OF HERCULES.

The Pillars of Hercules. By David Urquhart, M. P. Harper & Bros.

We shall not wonder at the learning of this book, if we reflect upon the antiquity of the author's family, which is clearly traced by his ancestor, Sir Thomas Urquhart, it is said, all the way down quite from its founder Adam. Antiquarian lore must have come to such a man as an inheritance; and the Hebrew and other roots been the daily fare of his childhood. The family, by all accounts, appear to have suffered little from the accidents of time, so unfortunate to the Cæsars and Plantagenets of modern days, and to have happily weathered the deluge without material damage. Escaping the difficulty which occurred at Babel, and luckily declining to join the party of ten tribes that left Judea with Shalmanezer on a visit to Assyria, and never have been heard of since, they continued safe through all the perils of the siege of Jerusalem, as they had formerly done in that of Troy. It is surprising that they should not have been crushed, as so many other ancient houses were, in the terrible Fall of the Roman Empire, or distracted by the uproar of the French Revolution; but the book before us is good evidence that they sustained no material hurt from either, but continue in existence still, as vigorous as ever.

The travels commemorated in the "Pillars of Hercules" will be discovered, on perusal, to differ considerably from ordinary ones. The unities of time and space are as severely preserved in them as in an ancient tragedy or epic. After musing upon its pages for many an hour, the reader is surprised, on coming to himself, to notice that so little ground has been gone over, and so few days spent. The truth is, that when he gets to the end of the volumes, he has been hardly anywhere after all, save to a dozen places or so, skirting the north and south shores of the Mediterranean Sea. How, then, is the reader cheated into thinking himself a traveller, when he has actually made little more advance in space during the whole time, than an Erie locomotive would carry him in four-and-twenty hours? In this way. He is introduced within a Louvre of reliquiæ, which have floated upon the stream of time, principally, the author thinks, from Phenicia or thereabouts, down to the parts of Spain and Morocco washed by the great Inland Sea. Their antiquities of dress, arts, names, and customs, he seizes and discourses on, as a professor does on specimens of minerals, both dug up alike from the overlying debris of ages.

There is an amusing play of the imagination among etymologists and antiquarian travellers, in running up the genealogies of speech and customs to their tiny sources among the shadows of the dim and distant past. Our traveller is, perhaps, not entirely exempt from a slight degree of quixotism, any more than the many others who have bestridden their Rosinantes before him. But though enthusiasts, deep-grounded in ethnology, are very serious themselves in their laborious excavations of long-interred knowledge, they nevertheless exhibit a smack of humor to lookers-on like us. Does not genuine wit, for instance, flow from the ingenious lucubrations of Horne Tooke, or the learned Noah Webster, when, with a flash of light, they reveal the dark relationship of obscure, forgotten etymologies, and tickle us by sudden shifts of phrase with unexpected surprises, which everybody knows to be the soul of wit?

To inquisitive people, of our traveller's turn of mind, the present is of little or no other consequence than as it reminds them of something that has existed a long while ago. Should an individual of this description happen to be an American, he does not make himself uncomfortable at home, till he has gone abroad, actually crossed the Atlantic, seen an English dwelling-house, and eaten a French roll. Not he. It would not be the object of such a person to witness the improvements of modern ingenuity, but to get as near as possible to the imperfect originals from which they sprang. Accordingly he stops not for anything by the way, but presses on his journey till he has attained the summit of his wishes, by sleeping in an Arab tent upon the desert, eating there his kus-couss-oo, and putting on the haik of Barbary. In these he recognises the primitive clothes, bread, and shelter--the three prime essentials of existence--in the unadulterated condition in which Abraham himself enjoyed them; and has the satisfaction at the same time of having turned his back upon the labors of more than a hundred generations that have succeeded.

The honorable member has learnt in Parliament, or elsewhere, to speak his mind quite frankly on all matters he encounters, from gunpowder and Gibraltar to a lady's fan and foot. At one time he compliments the Mediterranean Sea, as follows:--

"This is a spot which has influenced the destinies and formed the character, not of one but of many people.... The doubtful inquirer came hither to see if the sky met and rested upon the earth; if Atlas did indeed bear a starry burden; to discover what the world was; whether an interminable plain, or a ball launched in space, or floated on the water; whether the ocean was a portion of it, or supported it; whether beyond the 'Pillars' was the origin of present things, or the receptacle of departed ones; whether the road lay to Chaos, or to Hades.

"And something, too of these feelings crept over me, even although I came hither merely to ruminate on the past deeds of men.... The Mediterranean has made the world such as it is. Ancient history has been balanced on its bosom; and without the passage connecting it with the ocean, none of the events of recent history could have happened.

* * * *

"Let us suppose that the gap" (the gut of Gibraltar) "had been just wide enough to supply the water lost by evaporation, for which the thousandth part of the present passage would suffice, the Mediterranean would have been a salt-pan." [Pillars of Hercules volume 1 pages 8-9]

He afterwards speaks of this respectable piece of water in terms not so courteous--indeed, not a little blunt:--

"The Mediterranean," says he, "is like a bag with two necks, filling at both ends. The current through the Dardanelles presents exciting varieties, but no perplexing mysteries.... At Gibraltar all is disorder--the stream incessant--the level on both sides the same. The tide rises and falls, yet the current always runs out of the ocean, and into the Mediterranean..... What becomes of all this water? It cannot go to the Black Sea, from which the Mediterranean receives water; it cannot escape by a subterranean passage into the Red Sea, for the level of the Red Sea is higher by thirty feet. Then there is an under current discharging the water back again into the ocean."

But how is the extraordinary phenomenon of two opposing currents to be accounted for? Says Mr. Urquhart: "the solution is, an under current, produced by a difference of specific gravity between the water of the Mediterranean and the ocean. Sitting on Partridge Island (a small rock within the Straits), the question occurred to me, What became of the salt? If the water evaporates, the salt remains. Here then is the sluice of a mighty salt-pan--where is the produce?" As it is not deposited, his conclusion is, that by increasing the density of the surface and settling, a counter-current is produced, which returns to the ocean.

Though the rock of Gibraltar, by a rough calculation he has made, has cost his country upwards of 250 millions of dollars, he does not deem it after all a very valuable stone in the British diadem. On the contrary, "if any one were to do us the favor of taking it off our hands, we should save 150 millions more, for the interest of that sum is absorbed by its yearly outlay."

At times, there is something exceedingly refreshing in the positive tone of Mr. Urquhart upon controversial points, whether trivial or important. It steadies one's nerves very much to see a trembling balance of dubiety settled one way or the other with decision. This grace our traveller has in a conspicuous degree, and exhibits it on all questions, no matter whether they relate to the Stone of Hercules, or the discovery of soap. Assuming him to be a mere civilian, he certainly pronounces with admirable assurance upon the military capabilities of the works of Gibraltar, and their value to the British crown. He is convinced that, if not exchanged for Cuba, they ought unquestionably to be given up, being used at present only as an engine to irritate the Dons, for plundering the treasury, and encouraging and protecting a smuggling traffic into Spain. Everybody except a few English, that he has spoken to, he represents as being of the same opinion. If that celebrated rock reflects glory upon any people, it is upon the Moor, who made it what it is, and not on those who have obtained it by fraud or force.

In a short excursion in the vicinity of the Rock, the writer falls in with foul weather, and has a taste of the perilous want of harbors on the coast:--

"During three months I had seen nothing but clear skies and smooth seas. I could now feelingly revert to the words of a Spaniard, who, when Philip V. asked which were the principal harbors of Spain, answered-- 'June, July, and Cadiz.'"

Of Mr. Borrow, whose "Bible in Spain" was once much read in this country, the Spanish people are represented to entertain no favorable reminiscences:--

They imagined him to be a gipsy, he says, by his talking their language. I consequently, inquired about him as the English Gipsy. They did not comprehend me; but recollected a tall man, who was always writing; holding up their hands, they exclaimed, 'we thought he was writing some learned things, and not lies about poor people like us.'” .... "It is the misfortune of Spain to be misrepresented. She has been the subject of two standard and classical works—Don Quixote and Gil Blas. The former, by its sterling worth has made its way into the literature of other countries. Being a satire upon a particular temper and habit of mind, the scene and personages of which are Spanish, it is accepted as a description of Spain. As well might England be studied in 'Dr. Syntax.' Those peculiarities which it is intended to ridicule, and those extravagancies which are exaggerated in order that they may be exposed, are, to the stranger, the instructive portion of the work.

“Gil Blas is a romance by a Paris bookmaker, and owes its celebrity to an admirable sketch of a great minister, another of his successor, and an episode portraying Spanish manners. The barber Olivarez, the Count-Duke, and the story of the adventurer himself, in his retirement, are all taken from the Spanish, and give to the work its value. It is then dressed up with Spanish peculiarities, and Madrid or Paris morals, and passes from hand to hand as a mirror of the Spanish mind."

[Pillars of Hercules volume 1 pages 72-3.]

Mr. Urquhart visits a certain club.

"I was invited," says he, "in the evening to what I was told was a club. The place was an apothecary's shop. I was introduced into a sort of vault, and I found myself in a gambling establishment." This was at Tarifa in Spain. "Their cards were like those used by the Greeks; the club being represented not by the French trefoil, but by a club; the spade by a sword; the heart by a cup; and the diamond by a gold coin. The names being Bastones, Espados, Copas, Oros. The conversation having turned upon cards, I mentioned its supposed astronomical origin; the four seasons represented by the four suits; the fifty-two weeks by the number of the cards, and the thirteen lunar months by the thirteen tricks, proving whist to be the original game. I was here stopped. They had only twelve tricks and forty-eight cards; and 'of course,' said a Spanish Major (a Mr. Kennedy), 'our game is more scientific, because adapted to the Julian Calendar ! ”

So frail is the fabric of antiquarian theories. The grave politicians of this club

"could not recover from their astonishment at perceiving that there existed a human being who could question the wisdom, far less the sanity, of their imitating England and France.... 'England and France,' said they, 'are great and powerful; must we not imitate them and become so too?' I submitted, that imitation is more difficult than invention; that it requires a perfect knowledge of the thing imitated, in which case there could be no reason to copy; besides, it was impossible to copy institutions. 'In what particular,' I asked, 'would you copy us? Two things only have we to offer you as sanctioned by English consent—the Guelph Family, and Johnson's Dictionary! Will you have them in lieu of the Bourbons and the Castilian?'" [Pillars of Hercules volume 1 pages 76-7.]This view of imitation appears to us original.

"At Porta St. Maria, opposite Cadiz, I found a similar Moorish ruin. This is the point of embarkation of Xeres, or the Port of Sherry. It is the place for tasting wines; the Pacharete, Montillado, and most noble Mansanilla. The cellars are worth seeing; if spacious and lofty edifices can be so called.

"The people of Cadiz neither put their bodies in graves, nor their wines in cellars; the dead are built up in walls, resembling bins of a wine cellar; their wines are deposited in structures like cathedrals. The niches are like the dwellings of the living, some for ever and a day, others for a term of years; after which the fragments of the former tenant are ejected, and the place swept clean for another.

"I observed, on a placard, the two following signs of progress and civilization, in titles of new works— 'The Defender of the Fair Sex,' and 'The Ass, a beastly periodical.' The words were, “Il Burro, periodico bestial.'

"You may see a long row of boys, very small at one end and full grown at the other, dressed out in the sprucest and gayest uniforms—blue coat, single breasted, with standing collar and large flaps ; gold buttons and lace, white trousers mathematically cut, and strapped down on very camp-like boots; and, on inquiring what military institution this belongs to, you are answered, 'It is a boarding-school !'

"They have, in connection with schools, a practice which might suit 'Modern Athens.' I mean the hyperborean one. A person from each school goes the round of the town, calling for the boys in the morning, and dropping them in the evening; just as sheep, goats, or cows are collected by a common herd."

[Pillars of Hercules volume 1 page 131.]

The declension of Spain has been truly marvellous.

"Within a few months from the battle of Guadalete in Spain (which was decided in favor of the Mussulmans against the Christians), the Moorish troops had passed beyond the Pyrenees, and were encamped at Carcassone. There the tide of victory was arrested, not by the hammer of Martel, but by orders from Damascus. The empire established by this victory is the most remarkable instance of prosperity that the world has ever seen. The town of Corduba contained 200,000 houses; in its public library there were 600,000 volumes. It had 900 public baths. On the banks of the Guadalquivir there were 12,000 villages; and such were the fruits they drew from the soil, such the profits of their industry, which furnished to the East luxuries and arms, that the public revenue of Spain in the tenth century was equal to the collective revenues of all the other kings of Europe—twelve millions of dinars—a sum of gold which, calculating the dinar at 10 shillings, and multiplying by ten, to give the difference of the value of gold, is equal to sixty millions of pounds sterling of our present money!" [Pillars of Hercules vol 1 page 141.]

His learning in ladies' dresses is as conspicuous as in politics, antiquities, or war. What he says of the Montilla de Jiro and de Blonda, ought to be extracted, but there is no possibility of doing it on this occasion, without neglecting one or two other matters, which cannot be omitted. He must, however, be allowed to remark, that

"the mantilla is not spoken of as a piece of dress, that fits well or ill. Such a lady, they say, wears her mantilla well, just as if they were speaking of a ship carrying colors. The port of a Spanish lady is, indeed, like the bearing of a ship. The mantillas, reversing the effect of our costume—which is to impress the wearer with the feelings of a block — gives at once freedom and dexterity. The mantilla, fan, castanet, guitar, and dance—which last is not here the business of the legs only—keep the arms always busy. The head is disencumbered of bonnet, cap, ribands, and curls; hence that grace of the Spanish women, which all recognise and none can describe, for mere form or feature does not explain it.

"I need not say, that beneath a mantilla there are no curls; nor need I add, that where neither bonnets nor caps are worn, and the head is always exposed, the hair is well kept. A Spanish lady remarked to me, that what struck her principally when she travelled in other countries, was the want of cleanliness in the women's hair. It is (the Spanish lady's) always exposed, as hair was intended to be, to the air and wind, and it is every day in water, for they wet it before using the comb....

"A Spanish woman is no less attentive to her foot and shoe than to her hair; from below the saga comes forth the plump leg in its creaseless stocking.... The old Spanish shoe is very low, and scarcely held at all at the heel; like the slipper of the Easterns it requires the action of the toes to hold it on. The calf of the leg accordingly was full, because its muscles were called into play. So important is this to the grace and ease of the figure, that at Rome the models, male and female, lose their pension, if they wear a shoe with a thick sole. There still wants something to complete the Spanish costume, or, perhaps, I might say the Spanish woman—and that is THE FAN. Yet, how supply the want? at least, without herself—how convey her and it on paper? You might as well attempt to teach on paper how to roll a turban, make coffee, or hit the bull's-eye."

[Pillars of Hercules volume 1 page 148-154.]

The author's ardent attachment to Phœnicia and the Arabs, robs modern nations of the credit of many of the most splendid inventions, and readjusts the claims of some of the ancients to honors they have hitherto enjoyed, but are now in danger of forfeiting. The invention of glass is thus taken from the Tyrians or Egyptians, purely on the authority of Layard. The magnet, or stone of Hercules, the magnetic needle, and the compass, are, according to him, Arabian or Phœnician donations to mankind, driving the Celestials from the honor by a formidable attack from the heavy artillery of authors, arguments, and conjectures; scarcely conceding to them, and then not without great reluctance, the credit even of gunpowder itself. Dr. Franklin likewise will for aught we know, have to whistle for any reputation he will get hereafter for drawing lightning down from heaven, as Mr. Urquhart, we observe, has raised the ghosts of Salmoneus, Servius, and Sylvius Alladus, to call his claim in question. But the American philosopher, having, as is well known, given a large price for a whistle in his early days, will probably not lose his long worn honors, if whistling can prevent it. Besides all this, our traveller hints pretty strongly, that Americans should look upon the Phœnicians as the ancient discoverers of their country.

Much remains to be said even about the first volume of these interesting and learned travels, composed of a mosaic, where natural philosophy and imagination, archaeology, the arts, military and descriptive, ethnology, history, and political science, have each contributed a characteristic stone. But we cannot follow up the subject now. One thing we ought to notice--the argument or subject printed at the tops of all the pages. This, we believe, is by no means usual, but a very great convenience.

-- Literary World Volume 7 July 6, 1850 pages 5-7.

https://books.google.com/books?id=VTsZAAAAYAAJ&pg=PA5&dq#v=onepage&q&f=false

Related post:

- David Urquhart, eccentric ideologist

https://melvilliana.blogspot.com/2021/05/david-urquhart-eccentric-ideologist.html

Wednesday, June 2, 2021

The Smith College Library Rap

Melville biographer Newton Arvin was Professor of English at Smith College in Northampton, Mass. The Library honored in Jodi Shaw's great Library Rap has a large collection (18.5 linear feet; 43 boxes) of Newton Arvin papers. In 1938, as mentioned a few years back in the Melvilliana post

- Forty Years of Philip Hale on Melville

https://melvilliana.blogspot.com/2016/08/forty-years-of-philip-hale-on-melville.html

| |

|

"You go online and you take your pick

From the Five College Catalog just one click."

And the rare books, you know the written word

The name is Mortimer I don't know if you heard

The collection is deep the collection is wide

From medieval manuscripts to literary archives."

Yes! Acquired by "Gift: Mrs. Philip Hale, 1938" and described as follows:

SC/RBR: Original blue cloth (front free endpaper wanting; inner front hinge cracked); signature of Philip Hale cut and mounted on front flyleaf.

LOCATION: SC Rare Book Room Stacks / 825 M495m 1851

Just one click, after all:

Urquhartian David Urquhart? Data-based reality check

I wanted to test my idea that the adjective Urquhartian for Melville and contemporary readers of Pierre; Or, The Ambiguities in 1852 might have invoked David Urquhart (1805-1877), instead of or alongside his illustrious ancestor Thomas Urquhart (1611-1660), the Scottish writer and translator of Rabelais. Turns out the locution was exceedingly rare when Melville used it. Besides Melville's creative usage in Pierre, only two instances of the term Urquhartian occur before 1852 in ten databases listed below. The most relevant instance I have been able to find appeared in the London Spectator for February 10, 1849, referencing David Urquhart.

HathiTrust Digital Library

- 1818, polemical reference to one Thomas Urquhart--NOT Thomas the translator of Rabelais, but the author of Letters on the evils of impressment (London, 1816).

- 1849, The Spectator volume 22 (February 10, 1849) page 133. Urquhart's Last, mocking the "dilettante diplomatist" David Urquhart, M. P. who had formally requested the British Navy to report "On the use of Moone's prepared milk."

- 1852, Pierre; Or, The Ambiguities. "Urquhartian Club" invites teenage author to lecture on Human Destiny.

Same results as on HathiTrust, though possibly limited or filtered by algorithm.

Newspapers.com

- "Urquhartian-monomania" -- London Guardian, July 9, 1853

- Dundee Courier and Argus, May 27, 1862 (Scotland). Letter to the editor on "Fish-Cadgers" signed "Impartiality." The writer mocks the editor as "an inflated scribe, in the shape of an editor, who habitually issues from the press incendiary articles in the ultra-Urquhartian style, in the vain attempt to tarnish the reputation of England's greatest living statesman [Henry John Temple, Lord Palmerston]."

Genealogy Bank

https://www.genealogybank.com/

No hits for URQUHARTIAN

American Antiquarian Society Historical Periodicals Collection

https://www.gale.com/primary-sources/american-historical-periodicals

No results.

America's Historical Newspapers

https://www.readex.com/products/americas-historical-newspapers

No results.

ProQuest Civil War Era (1840-1865)

0 results.

19th Century UK Periodicals

https://www.nypl.org/collections/articles-databases/19c-uk-periodicals-i-ii

No results.

British Library Newspapers

- Liverpool Daily Post, October 19, 1855. Attacks on Joseph Mazzini by David Urquhart depicted (by Mazzini) as "Urquhartian mud, in which I really cannot condescend to stoop twice."

- "Ultra-Urquhartian" with reference to David Urquhart in letter signed "Impartiality" to the editor of Dundee Courier and Argus, printed there on May 27, 1862.

- London Graphic, November 6, 1886. TURKISH BATHS. Chiefly owing to the exertions of the clever but eccentric Mr. David Urquhart, who was a familiar figure to the last generation, the Turkish bath has taken its place as a permanent British institution. But, although it came into popular use about a quarter of a century ago, it has never attained that universal acceptance which its introducer predicted for it…. Would it were otherwise; for the Turkish bath, though not without its defects, would be a boon and a blessing to those classes (the majority of the community) who rarely wash those parts of their bodies which are hidden by their clothes, and who do not change their underclothing as often as, on correct Urquhartian principles, they ought to do.

British Newspaper Archive

- David Urquhart, eccentric ideologist

https://melvilliana.blogspot.com/2021/05/david-urquhart-eccentric-ideologist.html