"No other newspaper carried so full and accurate an account of Melville’s career; the man who wrote 'The Literary Wayside' column for that Sunday was someone who had read and loved Melville’s work and had known him personally, at least in his last years. And he was not waiting for the next century to admire Moby Dick." --Jay LeydaPast Melvilliana posts have positively identified formerly unknown authors of early Melville criticism and notices, for example:

- "Proteus" of the Newark Daily Advertiser is Augustus Kinsley Gardner

Augustus Kinsley Gardner is also "Caleb Quotem" of the New Orleans Commercial Bulletin, as Hershel Parker reveals in Melville Biography: An Inside Narrative.

|

The Century Magazine, January 1893 - publisher's ad for 1892 edition of Moby-Dick quoting "Charles G. Whiting, in Springfield Republican." |

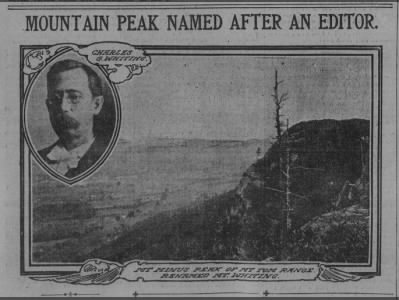

Charles Goodrich Whiting (1842-1922) was literary editor of the Springfield Republican from 1874 to 1910. Newspaper colleagues remembered Whiting for his deep love of nature, independent spirit, and "poetic temperament." According to the memorial published in the Springfield [Massachusetts] Republican on June 21, 1922, Whiting had belonged to the Authors' Club of New York City and enjoyed "literary friendships" with J. G. Holland, Edmund Clarence Stedman, and Richard Henry Stoddard among others.

Academic specialists in the critical receptions of Emily Dickinson and Henry James are ahead of Melville scholars here. Whiting is already known and honored in Emily Dickinson scholarship for early and perceptive criticism of Dickinson's first (posthumously published) volume of poems in his regular Sunday column, "The Literary Wayside." And Robin P. Hoople has extensively discussed Whiting's discerning reviews of Henry James in the Springfield Republican. Whiting's March 25, 1882 article for the Republican on "The Poet Longfellow's Death" received high praise from Joel Chandler Harris in the Atlanta Constitution as an exemplary "biographical sketch and critical estimate" and "one of the most remarkable essays of the kind ever written."

Very soon after Herman Melville's death on September 28, 1891, Whiting devoted the whole of his "Wayside" column to a long, thoughtful, and sincerely appreciative memorial of Herman Melville, published in the Springfield Republican on October 4, 1891. Jay Leyda stressed the uniqueness of this "extraordinary obituary article" in the historically friendly pages of the Springfield Republican, but Leyda did not know who wrote it:

"It may not have been the belittler of Moby Dick’s “preposterous heroes” [Leyda here refers to the anonymous reviewer of Melville's Clarel who called Ahab and the Whale "preposterous heroes"; Thomas Blanding assigns the July 18, 1876 review of Clarel to Frank Sanborn in the Spring 1977 Concord Saunterer.] who wrote the extraordinary obituary article on Melville that appeared in the first Sunday Republican after the death. No other newspaper carried so full and accurate an account of Melville’s career; the man who wrote “The Literary Wayside” column for that Sunday was someone who had read and loved Melville’s work and had known him personally, at least in his last years. And he was not waiting for the next century to admire Moby Dick." --Another Friendly Critic for Melville - New England Quarterly 27 (June 1954): 248.In the second volume of Herman Melville: A Biography, Hershel Parker quotes extensively from the unsigned 1891 article without identifying the admiring author. More (not all!) of the 1891 Springfield Republican article has long been available at the pioneering and still sturdy Melville site The Life and Works of Herman Melville. Nevertheless, the identification of the author as Charles Goodrich Whiting is another Melvilliana exclusive...

|

| Melville obituary-essay by Charles Goodrich Whiting (1842-1922) Springfield [Massachusetts] Republican - October 4, 1891 - from the online Newspaper Archives at Genealogy Bank |

Herman Melville, one of the most original and virile of American literary men, died at his home on Twenty-sixth street, New York, a few days ago, at the age of 72. He had long been forgotten, and was no doubt unknown to the most of those who are reading the magazine literature and the novels of the day. Nevertheless, it is probable that no work of imagination more powerful and often poetic has been written by an American than Melville's romance of "Moby Dick; or the Whale," published just 40 years ago; and it was Melville who was the first of all writers to describe with imaginative grace based upon personal knowledge, those attractive, gentle, cruel and war-like peoples, the inhabitants of the South Sea islands. His "Typee," "Omoo" and "Mardi" made a sensation in the late forties, when they were published, such as we can hardly understand now; and from that time until Pierre Loti began to write there has been nothing to rival these brilliant books of adventure, sufficiently tinged with romance to enchain the attention of the passing reader as well as the critic. Melville wrote many books, but ceased to write so long ago as 1857, having since that date published only two volumes of verse which had no obvious relation to his previous work, and gave no addition to his literary reputation.

Herman Melville had old New England and Knickerbocker ancestry. His grandfather on his father’s side was Maj. Thomas Melville, one of the famous Boston tea-party, a soldier of the Revolution, and it is recorded that he was, so far as may be known, the last of all Americans who stuck to the cocked hat until his death. On the mother’s side his grandfather was that Peter Gansevoort who so well stopped by his defense of Fort Schuyler in 1777 the reinforcement of Burgoyne by the troops under St. Leger. Herman’s father, Allan Melville, was a merchant; but the boy had an adventurous disposition, and shipped when 18 as a sailor before the mast for Liverpool, and four years later became a sailor on the Dolly for a whaling cruise in the south Pacific. The captain was cruel, and he and another sailor left the ship at a harbor of one of the Marquesas islands. They made for the interior, and reached the valley of the Typee tribe, with whom by a singular fortune they became friendly. He was, however, held as a prisoner, and when he was finally rescued by a whaler, it was the occasion of a bloody fight. Melville spent two more years in the South seas, and on his return he electrified his countrymen with the book called “Typee: a Peep at Polynesian Life during a Four Months’ Residence in a Valley of the Marquesas.” The book rapidly passed through several editions; it was dedicated to Chief Justice Shaw of Massachusetts, whose daughter the author afterward married.

Mr. and Mrs. Melville made their home in Pittsfield on the edge of Lenox. The house was the old Van Schaack mansion on South street, a mile below the park, which Melville purchased in 1852, and named Arrow-Head, from the Indian relics found upon the grounds. Here, says the excellent historian of Pittsfield, J. E. A. Smith, he wrote “Moby Dick,” here also he wrote that strange vagary “Pierre, or the Ambiguities,” and also the “Piazza Tales,” romances to which he gave this name because they were mainly written on a broad piazza by the author on the north end of the house, which commands a bold and striking view of Greylock and the interviewing hights and vales. Mr. Smith adds: “’My Chimny and I,’ a quaintly humorous essay of which the cumbersome old chimney—overbearing tyrant of the house—is the hero, was also written here, as well as ‘October Mountain,’ a sketch of mingled philosophy and word-painted landscape, which found its inspiration in the massy and brilliant autumnal tints presented by a prominent and thickly wooded spur of the Hoosac mountains, as seen from Arrow-Head on a fine day after the early frosts.” Melville loved the Berkshire scenery with an ardent love and he dedicated his “Pierre” to “Greylock’s most excellent majesty,” saying:—

In old times authors were proud of the privilege of dedicating their works to Majesty. A right noble custom, which we of Berkshire must revive. For whether we will or no, Majesty is all around us here in Berkshire, sitting as in a grand Congress of Vienna of majestical hill-tops, and eternally challenging our homage. But since the majestic mountain, Greylock, my own more immediate sovereign lord and king, hath now, for innumerable ages, been the one grand dedicatee of the earliest rays of all the Berkshire mornings, I know not how his imperial purple majesty (royal-born: porphyrogenitus) will receive the dedication of my own poor solitary ray. Nevertheless, forasmuch as I, dwelling with my loyal neighbors, the maples and the beeches, in the amphitheater over which his central majesty presides, have received his most bounteous and unstinted fertilizations, it is but meet that I here devoutly kneel, and render up my gratitude, whether thereto, The most excellent purple majesty Greylock benignantly incline his hoary crown, or no.This dedication shows Melville’s later tendency to extravagance of rhetoric, which confused and diminished the effect of his real genius, and yet which perfectly fitted the astonishing book thus dedicated,—in which, surely, Greylock’s steadfast dignity and noble proportions found no literary counterpart.

Herman Melville later was appointed to a clerkship in the New York custom-house, and since then his home has been in New York city, where in the society of a few friends he has been content to see the world go by. He published a volume of war poems in 1866, and 10 years later his versified record of travel, "Clarel, a Pilgrimage in the Holy Land." Mr. Melville has not gained a place as poet, yet no one can read his book of “Batttle Pieces” without much admiration for the vigor of the verse, and the frequent flashes of prophetic fire which they show. It is startling to read these lines, called “The Portent”:—

Hanging from the beam,

Slowly swaying (such the law),

Gaunt the shadow on your green,

Shenandoah!

The cut is on the crown

(Lo, John Brown),

And the stabs shall heal no more.

Hidden in the cap

Is the anguish none can draw;

So your future veils its face,

Shenandoah!

But the streaming beard is shown

(Weird John Brown),

The meteor of the war.

The book is exceptional in that its verse was not suggested and put forth at the time of the events it wraps up in rhythmic guise, but after the fall of Richmond Melville wrote nearly all of the poems; they show, nevertheless, such differences of proportion as might have occurred from the spontaneity of immediate impulse. The verses on Worden, “In the Turret,” on Cushing, “St the Canon’s Mouth,” are not ordinary writing, nor is the poem “Chattanooga” on the battle fought in November, 1863, of which these are a few stanzas—there are not many in all:—

A kindling impulse seized the host

Inspired by heaven’s elastic air;

Their hearts outran their General’s plan,

Though Grant commanded there—

Grant, who without reserve can dare;

And, “Well, go on and do your will,”

He said, and measured the mountain then:

So master-riders fling the rein—

But you must know your men.

The summit-cannon plunge their flame

Sheer down the primal wall,

But up and up each linking troop

In stretching festoons crawl,

Nor fire a shot. Such men appal

The foe, though brave. He, from the brink,

Looks far along the breadth of slope,

And sees two miles of dark dots creep,

And knows they mean the cope.

He sees them creep. Yet here and there

Half hid 'mid leafless groves they go,

As men who ply through traceries high

Of turreted marbles show—

So dwindle these to eyes below.

But fronting shot and flanking shell

Sliver and rive the inwoven ways,—

High tops of oaks and high hearts fall,—

But never the climbing stays.

Here is a piece that makes one think of Gen. W. F. Bartlett,—Frank Bartlett, the knightly soldier whom Pittsfield counts her hero with pride, and who may well have been in Melville’s mind as he wrote of “The College Colonel”:—

He rides at their head;

A crutch by his saddle just slants in view,

One slung arm is in splints, you see,

Yet he guides his strong steed—how coldly, too.

He brings his regiment home—

Not as they filed two years before

But a remnant half-tattered, and battered and worn,

Like castaway sailors, who—[s]tunned

By the surf’s loud roar,

Their mates dragged back and seen no more,—

Again and again breast the surge,

And at last crawl, spent, to shore.

A still rigidity and pale, —

An Indian aloofness, lines his brow;

He has lived a thousand years

Compressed in battle’s pains and prayers,

Marches and watches slow.

There are welcoming shouts and flags;

Old men off hat to the boy,

Wreaths from gay balconies fall at his feet,

But to him—there comes alloy.

It is not that a leg is lost,

It is not that an arm is maimed,

It is not that the fever has racked,—

Self he has long disclaimed.

But all through the Seven Days’ fight,

And deep in the Wilderness grim,

And in the field hospital tent,

And Petersburg crater, and dim

Lean brooding in Libby, there came—

Ah heaven!—what truth to him!

Yet the better evidence of the divine afflatus that was in him appeared in his South Sea romances and in "Moby Dick"; his "Clarel" cannot be read except as a task, and contains probably nothing worth quoting, although some very patient reader might discover here and there lines of some consequence. Melville was very interesting in his personality, — a man above the ordinary stature, with a great growth of hair and beard, and a keen blue eye; and full of vigor and quickness of thought in his age,—which he felt and yielded to earlier than would have been expected of one of so stalwart a frame.

Although as aforesaid Melville's early novels are not now read, they are as well worth reading as the more sensuous stories of Pierre Loti, or the vivacious ventures of Robert Louis Stevenson, whose scenes are laid in the same region of "lotus eating," to describe in a fit phrase the common life of the Pacific islands. "Typee," particularly, would be found to retain its charm for even the sophisticated readers of to-day. But the crown of Melville's sea experience was the marvelous romance of "Moby Dick," the White whale, whose mysterious and magical existence is still a superstition of whalers,— at least such whalers as have not lost touch with the old days of Nantucket and New Bedford glory and grief. This book was dedicated to Nathaniel Hawthorne, and Hawthorne must have enjoyed it, and have regarded himself as honored in the inscription. This story is unique; and in the divisions late critics have made of novels, as it is not a love-story (the only love being that of the serious mate Starbuck for his wife in Nantucket, whom he will never see again), it is the other thing, a hate-story. And nothing stranger was ever motive for a tale than Capt Ahab's insane passion for revenge on the mysterious and invincible White whale, Moby Dick, who robbed him of a leg, and to a perpetual and fatal chase of him the captain binds his crew. The scene of this vow is marvelously done, and so are many other scenes, some of them truthful depictions of whaling as Melville knew it; some of the wildest fabrications of imagination. An immense amount of knowledge of the whale is given in this amazing book, which swells, too, with a humor often as grotesque as Jean Paul's, but not so genial as it is sardonic. Character is drawn with great power too, from Queequeg the ex-cannibal, and Tashtego the Gay Header, to the crazy and awful Ahab, the grave Yankee Starbuck, and the terrible White whale, with his charmed life, that one feels can never end. Certainly it is hard to find a more wonderful book than this Moby Dick, and it ought to be read by this generation, amid whose feeble mental food, furnished by the small realists and fantasts of the day, it would appear as Hercules among the pygmies, or as Moby Dick himself among a school of minnows.

--Charles Goodrich Whiting's memorial article on Herman Melville in the Springfield Republican, October 4, 1891Ten years later Charles Goodrich Whiting was still promoting Melville and Moby-Dick. The Springfield Republican summarized Whiting's remarks to the local Teachers' Club (including a fine appreciation, too, of Elizabeth Stoddard) in an article headed "A TALK ON AMERICAN NOVELS," published in the Springfield Republican on Wednesday April 24, 1901:

The fifth talk on novels before the teachers’ club by Charles G. Whiting was given last evening at the rooms of the club in the Young Men’s Christian association building. The subject was “The chief American novels.” A brief survey was made of the early novel writing, imitative to a degree of English originals....Find A Grave has more about Charles Goodrich Whiting from the 1922 obituary in the Springfield Republican.

The novels of Mrs. Elizabeth Stoddard were made note of, and it was said that “Two Men” and “Temple House” were among the “chief American novels,” and should have a high place in the esteem of students of our literature and of human life. Mrs. Stoddard was characterized as a great elemental genius. Also Herman Melville was brought to the attention of the audience as a magnificent imaginative writer; it was said that only the impossibility of recognizing a white whale as a hero, alongside of Macbeth or Achilles or Lancelot or—let us say,—Vivian Grey—prevented this book from taking its place as one of the great novels. In fact, “Moby Dick” is really an epic, and stands for the tragedy of the whale.... --Springfield Republican, April 24, 1901; found in the online Newspaper Archives at Genealogy Bank.

For a selection of his nature poetry, check out the entry for Charles Goodrich Whiting in the 1907 volume The Poets and Poetry of Springfield. It takes a poet to see through the monster to the hero.

The Saunterer by Charles Goodrich Whiting is digitized at Google Books.

Walks in New England by Charles Goodrich Whiting, also at Google Books.

Related posts:

- Also by Charles G. Whiting

https://melvilliana.blogspot.com/2016/08/also-by-charles-g-whiting-concerning.html

- Whiting on Elizabeth Stoddard and Melville

https://melvilliana.blogspot.com/2020/07/whiting-on-elizabeth-stoddard-and.html

- Gottschalk reminiscence by Charles G. Whiting https://melvilliana.blogspot.com/2024/10/gottschalk-reminiscence-by-charles-g.html

Great research!

ReplyDeletePosted on Melville Society Facebook page - see comment

ReplyDeletehttps://www.facebook.com/groups/themelvillesociety/