07 Feb 1916, Mon Pittsburgh Daily Post (Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania) Newspapers.com

07 Feb 1916, Mon Pittsburgh Daily Post (Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania) Newspapers.comNew Orleans Origins of Melville Revival: Armour Caldwell at Tulane, 1908

The Best Sea Story Ever Written.Less well known as active Melville advocates are two Massachusetts journalists: Charles Goodrich Whiting (1842-1922), editor of the Springfield Republican; and Philip Hale (1854-1934), the Boston music critic who championed Melville for forty years, thirty in his newspaper column "As the World Wags." In Butte, Montana, ladies of the "Homer Club" reserved a day in early 1907 for "sea tales" as part of their daunting program of literary study. Ethelyn Caldwell Adams (Mrs. John Coit Adams) originally was assigned Moby-Dick, but in February 1907 it was Mrs. L. P. Sanders who "presented a sketch of Melville, the author of 'Moby Dick.'"

03 Feb 1907, Sun The Anaconda Standard (Anaconda, Montana) Newspapers.com

03 Feb 1907, Sun The Anaconda Standard (Anaconda, Montana) Newspapers.comStill we speak of THE Revival, later than and distinct from the Melville "vogue" before the First World War (Zimmerman, page 23). THE Revival launched with the centenary in 1919 and Raymond Weaver's "foolish and enormously influential" biography, as Stanley Edgar Hyman called it. Martina Pfeiler and I will be looking at precursors, each with ties in New York City--predictably, considering the Columbia University connections of so many participants. Less predictably, one flowered in the South.

- Who was Armour Caldwell?

- What did he say about Moby-Dick? and

- What the devil is a picayune? (Answered first, with help from Grammarphobia: Anglicized version of picaillon, south Louisiana French for the Spanish medio real worth 6 1/4 cents, the smallest coin in circulation and the name of the daily newspaper in New Orleans.)

Who was Armour Caldwell?

What did Armour Caldwell say about Moby-Dick?

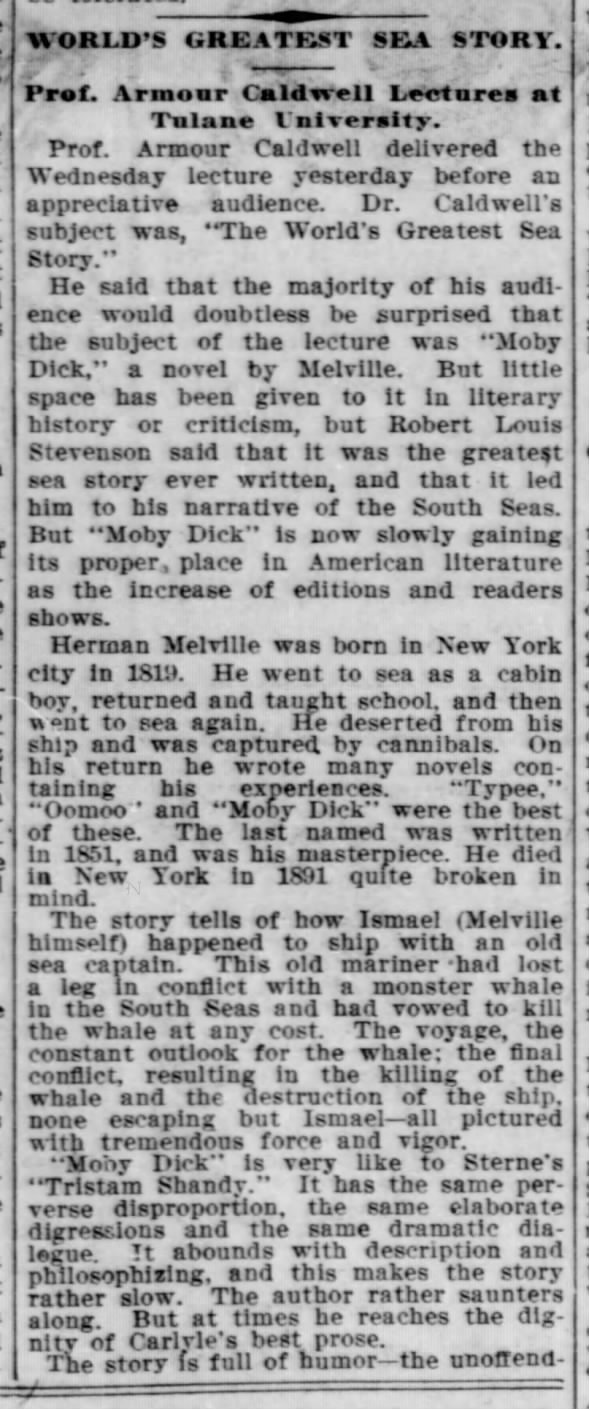

02 Apr 1908, Thu The Times-Democrat (New Orleans, Louisiana) Newspapers.com

02 Apr 1908, Thu The Times-Democrat (New Orleans, Louisiana) Newspapers.com

02 Apr 1908, Thu The Times-Democrat (New Orleans, Louisiana) Newspapers.com

02 Apr 1908, Thu The Times-Democrat (New Orleans, Louisiana) Newspapers.com

To begin with, Caldwell expected his audience to be "surprised" by the subject of his lecture, Moby-Dick, since "little space has been given to it in literary history or criticism." At the same the speaker did register "the increase of editions and readers." New editions then were the illustrated 1902 volume in the series of Famous Novels of the Sea by Charles Scribner's Sons; and the 1907 volume in Everyman's Library, edited by Earnest Rhys. Availability of these new volumes offered some hope that "Moby Dick is now slowly gaining its proper place in American Literature."

The story tells of how Ismael (Melville himself) happened to ship with an old sea captain. This old mariner had lost a leg in conflict with a monster whale in the South Seas and had vowed to kill the whale at any cost. The voyage, the constant outlook for the whale; the final conflict, resulting in the killing of the whale and the destruction of the ship, none escaping but Ismael--all pictured with tremendous force and vigor.

Of the Pequod's crew the newspaper names only Melville's narrator Ishmael ("Ismael"), reporting that Caldwell identified him as a stand-in for "Melville himself." But Caldwell keyed on "the old sea captain" and his inflexible, vengeance-driven quest. Enthralled by the revenge plot, the lecturer in both extant newspaper accounts has Moby Dick killed in the end, making Ahab a kind of Beowulf and the White Whale dead as the Dragon.

"It has the same perverse disproportion, the same elaborate digressions and the same dramatic dialogue. It abounds with description and philosophizing, and this makes the story rather slow."

In 1851, William A. Butler [Correction: literary editor James C. Welling reviewed Moby-Dick in his regular "Notes on New Books" column for the Washington National Intelligencer, as I discovered in August 2024.] had said much the same thing when reviewing Moby-Dick for the Washington National Intelligencer. With the help of Mary K's black book on Melville's Sources, we can readily find pertinent scholarship through 1987. In the Hendricks House edition of Moby-Dick, Luther S. Mansfield and Howard P. Vincent particularize debts to Tristram Shandy for the cozy "confidential disclosures" between Ishmael and Queequeg as bedmates in Chapter 10 A Bosom Friend; and for the figure of Cervantes in Melville's apostrophe to "thou Just Spirit of Equality" and "great democratic God!" in Chapter 26 Knights and Squires.

After Sterne, Caldwell named Carlyle as a major influence on the elevated style in Moby-Dick which occasionally "reaches the dignity of Carlyle's best prose." Here again later scholarship has abundantly confirmed Melville's debt to Carlyle, which seemed obvious not only to Caldwell but also to the earliest critics of Moby-Dick (and before that, Mardi). Friendly ones regretted Carlyle's bad influence; hostile ones condemned it. Caldwell's Columbia teacher and colleague William P. Trent counted as a knock, Melville's "obvious imitation of Carlylean tricks of style and construction." MacMechan the Carlyle expert never named the author of Sartor Resartus. In the new 20th century, however, imitations of Carlyle sounded fine to Caldwell, another descendant of Scots.

In the Extracts section of Moby-Dick Melville quotes from Goldsmith's History of the Earth and Animated Nature. But Caldwell names Goldsmith as one of Melville's more important influences for his "unoffending humor," not his geology or zoology. The 1906 anthology, English Humorists of the Eighteenth Century, groups Goldsmith with Sterne, Addison, and Steele, providing a handy collection of possible influences on Moby-Dick. For his part, Melville once scorned the sort of imitation that Caldwell alleges: "We want no American Goldsmiths." Ironically, Melville's own debt to Washington Irving's graceful way of travel writing was already manifest to Evert Duyckinck in 1847, as John Bryant points out in Melville and Repose. What Bryant elsewhere calls "the Ishmaelian mode" carries on "the 'amiable tradition' of British humor" and is characterized by "geniality" (1994, Comic Debate, page 1). In contrast to the early recognition of Melville's debts to Carlyle, recognition of the Goldsmith (English or American) in Ishmael is really a 20th century insight.

Caldwell also addressed philosophical and psychological dimensions of Moby-Dick:

"But Melville has a great power of philosophy also. The powerful strokes with which he depicts the gradual decay of the old captain's mental faculties is as subtle a piece of psychological insight as one will find in fiction.... "

-- New Orleans Times-Democrat, April 2, 1908

Caldwell understands Ahab's whale-mania as a variety of progressive mental illness. The lecturer's appreciation of Melville's "psychological insight" anticipates scholarship on Ahab's "madness" or "insanity," hinting perhaps at the clinical focus of more recent work in the genre of disability studies, rather than psychoanalytic readings inspired by Freud and Jung.

|

| New Orleans Daily Picayune - April 2, 1908 - page 5 via Genealogy Bank |

Caldwell ended by quoting a student reader who

"after reading Moby Dick told me that he thought it was a symbol, or had a meaning that it was the story of man's pursuit after his heart's desire, how after a long, hard journey it was only gotten at the end of the voyage, and then both go down together in the awful abyss."

-- Daily Picayune, April 2, 1908

The Picayune reported also that Caldwell "had planned last summer to write Melville's life, but he found some on was already at work on it." It's too bad Caldwell gave up on the idea, since contemplated biographies by J. E. A. Smith, Arthur Stedman, Frank Jewett Mather, and Melville's daughter Elizabeth ("Bessie") never materialized.

Caldwell's Tulane lecture marks the earliest known phase of the specifically academic Melville Revival. Archibald MacMechan had already praised Moby-Dick as "The best sea story ever written." But MacMechan's view of Moby-Dick as best-sea-story-ever did not employ now familiar terms of formal literary analysis. As V. L. O. Chittick points out, "Symbolism, allegory, myth, ritual, and literary sources are not discussed--nor, of course, are fixations, complexes, and compulsions." At Tulane, Armour Caldwell did speak of 18th century literary influences on Moby-Dick, citing Sterne for the technique of narrative expansion through digression and dialogue; and Addison, Steele, and Goldsmith for inoffensive, British-style whimsy. Caldwell explicitly addressed the problem of literary symbolism, sharing the response of a student reader struck by the symbolic meaning of Ahab's quest as "man's pursuit after his heart's desire." And Caldwell did address Melville's treatment of "complexes and compulsions," judging the portrayal of Ahab's monomania to be "as subtle a piece of psychological insight as one will find in fiction." Moby-Dick as a great story is one thing. Moby-Dick as the deserving subject of literary analysis and study is another. At Tulane in 1908 Armour Caldwell bequeathed it to fellow English Majors, for better or worse.

Works Cited

American Leader, volume 1 number 1. February 29, 1912. Photo and bio of Armour Caldwell, Managing Editor on pages 10 and 11.

Aronoff, Eric. "The Melville Revival" in Herman Melville in Context, ed. Kevin J. Hayes (Literature in Context, pages 296-306). Cambridge University Press, 2018. doi:10.1017/9781316755204.030Bercaw, Mary K. Melville's Sources. Northwestern University Press, 1987.Bryant, John. Melville and Repose: The Rhetoric of Humor in the American Renaissance. Oxford University Press, 1993.

Bryant, John. “Melville, Twain and Quixote: Variations on the Comic Debate.” Studies in American Humor, New Series 3 number 1, 1994, pages 1–27. JSTOR, www.jstor.org/stable/42573302.

Chittick, V. L. O. “The Way Back to Melville: Sea-Chart of a Literary Revival.” Southwest Review volume 40 number 3 (Summer 1955) pages 238–248. JSTOR, www.jstor.org/stable/43464100.

Hyman, Stanley Edgar. The Promised End. World Publishing Company, 1963.

Irving, Washington. Washington Irving's Sketch book. With introduction by Brander Matthews and notes by Armour Caldwell. New York: Longman's, Green, and Co., 1905.

MacMechan, Archibald. "The Best Sea Story Ever Written" in Queen's Quarterly volume 7, October 1899, pages 120-130.Marovitz, Sanford E. The Melville Revival chapter 33 in A Companion to Herman Melville, ed. Wyn Kelley. Blackwell, 2006.

Manley, Marian C. A Worm's-Eye View of Library Leaders. Wilson Library Bulletin volume 27 (November 1952) page 233; reprinted in An American Literary History Reader, ed. John David Marshall (Shoe String Press, 1961) pages 150-160 at page 155.

Melville, Herman. Moby-Dick; Or, The Whale. Ed. Luther S. Mansfield and Howard P. Vincent. Hendricks House, 1952.

Pfeiler, Martina. “‘The Time has Come for a Melville Revival’: Edwin Emery Slosson’s Journalistic Contributions to the Origins of Melville’s Revival in New York City.” Conference paper presented June 17, 2019 at the 12th International Melville Society Conference in New York City.Riegel, O. W. “The Anatomy of Melville's Fame.” American Literature volume 3 number 2 (May 1931) pages 195–203. JSTOR, www.jstor.org/stable/2919779.

Trent, William P. A History of American Literature, 1607-1865. New York: D. Appleton, 1903. Pages 389-391 at 390.

Zimmerman, Michael P. "Melville in the 1920's: A Study in the Origins of the Melville Revival, with an Annotated Bibliography." PhD dissertation. Columbia University, 1963.

- Moby-Dick widely praised in 1851-2

https://melvilliana.blogspot.com/2020/02/moby-dick-widely-praised-in-1851-2.html

- Forty years of Philip Hale on Melville

https://melvilliana.blogspot.com/2016/08/forty-years-of-philip-hale-on-melville.html

- Charles Goodrich Whiting

https://melvilliana.blogspot.com/2016/08/charles-goodrich-whiting-author-of.html

Was Caldwell the same guy who had an autograph book with Melville's signature?

ReplyDeleteNo that was Lafayette Cornwell.

Deletehttps://melvilliana.blogspot.com/2020/10/tell-truth-and-shame-devil.html