Reading Moore's poems one soon becomes aware of his obsessive fondness for the word "some".... --MacDonald P. Jackson, Who Wrote "The Night Before Christmas"? page 73.

If dearest hopes that fill the youthful mind,In chapter 15 of Who Wrote "The Night Before Christmas"?, MacDonald P. Jackson identifies and tabulates six of Clement C. Moore's supposedly favorite expressions, noting with satisfaction that none occurs in "A Visit from St. Nicholas" aka "The Night Before Christmas." Hey Santa Claus! What just happened? Somehow Moore got boxed out of his own Christmas poem.

And joys of fairest promise, end in gloom,

Yet still, successive hopes we ever find,

And other joys, upspringing in their room.

No, let not frigid age regard with scorn

The youthful spirit's warm outbreakings wild:

How many a hero to the world is born

Whose deeds are but the reckless darings of a child!

--Clement C. Moore, A Trip to Saratoga

Leaving aside most of Moore's unpublished manuscript poems, Jackson accurately counts 160 instances of six "favorite expressions" in poems by Moore, and only 9 in poems attributed to Livingston. Readers have to guess Jackson's criteria, since he never gives any. Wherefore these six?

some = 75-3The unstated guiding principle appears to have been, find expressions that Moore uses way more than Livingston does, while silently rejecting words and phrases that occur also in "A Visit from St. Nicholas." Many Moore favorites that Jackson slights or excludes in chapter 15 of Who Wrote show up in "A Visit from St. Nicholas." Of course, counting more Moore-markers than Jackson allows might lead people to think Clement C. Moore wrote the beloved rhymes--like the good man said he did, "not for publication, but to amuse my children."

oft = 30-1

many a = 17-0

in vain = 16-2

at length = 12-3

that's = 10-0

|

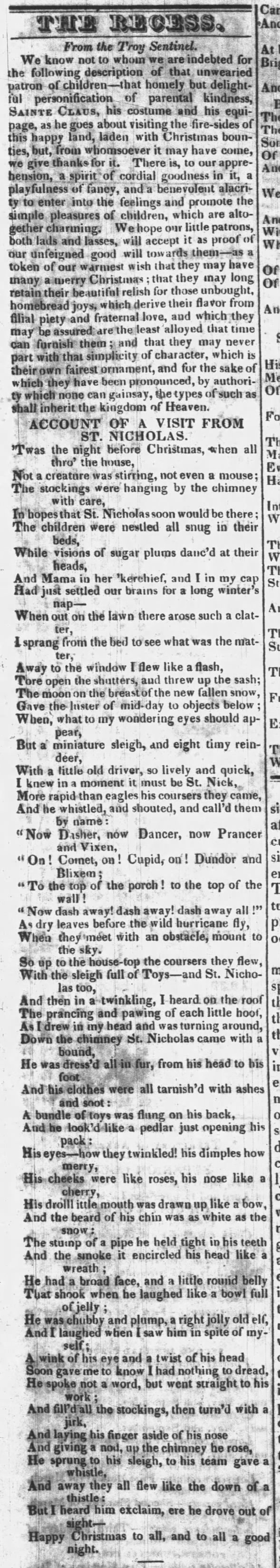

| New York American - March 1, 1844 |

One fantastic Moore marker that Jackson absolutely should have counted among Moore's "favorite expressions" is the word should, occurring 38 or 68 times in Moore's poems, depending on your data set, to Livingston's measly three, all of which occur at the start of lines in one piece, a verse translation of Habakkuk 3.17-18. Livingston's three Should's are reflexes of the biblical source for his hymn. Other translations of the same verses feature modals in the same places, typically either shall or should. Outside of Habakkuk, Livingston just never bothers with "should." A similar and suggestive disparity exists in their usages of the word would. The contrast is especially evident when you count all of Moore's manuscript poems: 137 instances of "would" in Moore's poems to 18, maybe, in Livingston's. Demonstrably, Henry Livingston, Jr. tends to avoid conditional verb forms constructed with the modals should and would. (Well then, what about "could"? Turns out the disparity persists for could, though not quite so dramatically: 76 instances in Moore's larger set of poems, including "Biography of the heart" and other manuscript works, vs. 18 in Livingston's.)

One of the best Moore-markers in the world is the word "like" which Moore uses 132 times, at least, to Livingston's 15. Moore employs like most often to construct similes using "like," which Livingston does rarely, as the numbers demonstrate like ringing a bell. Jackson would excuse his neglect of would and should and like in chapter 15 by pointing out that would is treated with high frequency words in chapter 16, should and like with medium-high frequency words in chapter 17. But would and should and like are too useful for differentiating Moore from Livingston to bury in a statistical table where numbers replace words and effectively mask their real identity, meaning, and literary value. In fact, these three words scream, "C.C.M. was here!"

Since Jackson selected "oft" he ought to have picked the similarly conventional and poetic word "ere," too: 17-2 for Moore, or 48-2 counting more of Moore's manuscript poems. Revealingly, the two usages of "ere" for Livingston both occur in a poem he probably did not write, the 1819 Carrier Address.

It's also fair to say, mathematically speaking, that Livingston has little hope. Various forms and compounds with hope (hopes, hopeful, hopeless, and hop'd) occur 56 times in all of Moore's poems, but only three in Livingston's. Another word that Livingston does not like nearly so much as Moore does is "soon" (plus "Soon"): 68 instances counting "Biography of the heart" (3x) and other manuscript poems, vs. only 8 for Livingston. Moore's 68 include one instance in a line from "Charles Elphinstone" that also contains the word "dread." As in Moore's "Visit," dread gives way to joy:

Here then is my personal Christmas list, way ahead of schedule, with eight great "favorite expressions" of Clement C. Moore. My data set of Moore's poems includes his manuscript poem, Biography of the heart. For now I left out "soon" (and a few others) to get a tighter cluster of eight words, as numerically close as I can manage to Jackson's six "favorite expressions." All eight make great Moore-markers that count, or should count, when you're trying to get at essential and distinctive, and potentially distinguishing elements in the verse style of Clement C. Moore.

Five shorter poems by Moore yield no hits in Jackson's Table 15.1. Thus, Moore's Old Dobbin gets zero hits from Jackson's rigged list, but one "like" from mine. Another short poem, Moore's To a Young Lady on her Birth-day, yields zero hits from Jackson's six, but two instances of "like" from mine, plus one "Ere" and one "hope," making four hits to Jackson's none. Flowers? Zip for Jackson's, 3 for mine (would 1x and should 2x). Moore's manuscript Valentine for Fanny French contains none from Jackson's list favorite expressions, but one "hope" marks it for Moore. The brief manuscript poem that Jackson refers to as "To Clem" is actually titled To Little Clem. from a little girl according to Mary S. Van Deusen's transcription. Jackson's list offers no help, but Clem yields one "like" from mine. Result: all five short poems that Jackson's list could not identify as Moore's contain at least one of the eight great Moore-markers herein commended. My list beats Jackson's 5/5 times.

Jackson's average being one favorite locution every 129 words, a long poem like Moore's Yellow Fever of 1135 lines should yield nearly 9 hits, but gets only 6. Mine gets

For The Pig and the Rooster, Jackson's 5-count is only slightly lower than his expected average of 6 for a poem of 783 words. A nice round ten can be expected from mine, which actually yields thirteen: 7 instances of like, 2 hits each for should and would, one ere and one brain.

I've got 9 of 14 expected hits for a poem the size of The Wine Drinker (1069 words); and 14 of expected 15 in The Water Drinker (1131 words); compared with Jackson's better 10/8 for "Wine Drinker" and somewhat worse 5/9 for "Water Drinker."

Among the manuscript poems, Moore's Irish Valentine at 590 words most closely approximates the word-total of 542 in "A Visit from St. Nicholas." "Irish Valentine" should yield between four and five hits from Jackson's list but only gets one. How fares it with mine? Five likes, one brain, and one hope for a solid 7 of my expected 7.6. From Jackson's list two manuscript poems by Clement C. Moore, Caroline's Album and To Eliza, in England get zilch. From mine? should-1, would-3, and like-1 for a total of 5 hits in "Caroline"; and one would for "Eliza," which I guess is better than nothing.

Among longer Moore poems with seemingly too-few hits on Jackson's Table 15.1, Natural Philosophy shows only one hit of 4-5 expected in 590 words. Counts for our great eight: should-2; would-5; like-2; dread-1; a total of 10 when we expected about 8, on average.

How about Moore's misunderstood manuscript poem From Saint Nicholas? Five Moore-markers there (hope-2; would-1; like-2), or four if you don't like "like" as a main verb. And we only needed three to match the expected average for a poem of 214 total words.

In a poem by Clement C. Moore of 542 words, seven occurrences of words from our list of eight great favorite expressions can be expected, on average. The Night Before Christmas has 15; with a frequency rate of 1 in 36 words. A Livingston poem of 542 words (an ambitious, uncomfortable length for Livingston that he almost never attempted) on average would be expected to have not even two (542/300 = 1.81) of these eight words. Less than two, if Livingston's, and "The Night Before Christmas" has--how many? Fifteen!

Acknowledgments

One of the best Moore-markers in the world is the word "like" which Moore uses 132 times, at least, to Livingston's 15. Moore employs like most often to construct similes using "like," which Livingston does rarely, as the numbers demonstrate like ringing a bell. Jackson would excuse his neglect of would and should and like in chapter 15 by pointing out that would is treated with high frequency words in chapter 16, should and like with medium-high frequency words in chapter 17. But would and should and like are too useful for differentiating Moore from Livingston to bury in a statistical table where numbers replace words and effectively mask their real identity, meaning, and literary value. In fact, these three words scream, "C.C.M. was here!"

Since Jackson selected "oft" he ought to have picked the similarly conventional and poetic word "ere," too: 17-2 for Moore, or 48-2 counting more of Moore's manuscript poems. Revealingly, the two usages of "ere" for Livingston both occur in a poem he probably did not write, the 1819 Carrier Address.

It's also fair to say, mathematically speaking, that Livingston has little hope. Various forms and compounds with hope (hopes, hopeful, hopeless, and hop'd) occur 56 times in all of Moore's poems, but only three in Livingston's. Another word that Livingston does not like nearly so much as Moore does is "soon" (plus "Soon"): 68 instances counting "Biography of the heart" (3x) and other manuscript poems, vs. only 8 for Livingston. Moore's 68 include one instance in a line from "Charles Elphinstone" that also contains the word "dread." As in Moore's "Visit," dread gives way to joy:

But soon their dread was for delight exchang'd.The word dread, as Don Foster showed accidentally, meaning to discredit Moore, in fact makes a splendid Moore-marker: 11 or 24 to nothing, depending on how much of Moore's unpublished cosmic allegory Charles Elphinstone you can handle. If Jackson's criteria for selection of "favorite expressions" were strictly and objectively mathematical, he should at least have included the words should, ere, dread, vision/s, and brain/s, and (why not?) also forms and compounds with hope.

Here then is my personal Christmas list, way ahead of schedule, with eight great "favorite expressions" of Clement C. Moore. My data set of Moore's poems includes his manuscript poem, Biography of the heart. For now I left out "soon" (and a few others) to get a tighter cluster of eight words, as numerically close as I can manage to Jackson's six "favorite expressions." All eight make great Moore-markers that count, or should count, when you're trying to get at essential and distinctive, and potentially distinguishing elements in the verse style of Clement C. Moore.

should 38-3 / (68-3)Numbers in parentheses give totals of favorite words in Moore's corpus when properly enlarged to include all of his manuscript poems, excepting translations. Grand Total: 499 vs. 42. On average that's 1 every 78 words for Moore's set of 38,714 words. For the six expressions in Jackson's list, "Moore averages one of his favorite locutions to every 129 words." For my great 8, the rate of frequency over Livingston's much smaller data set of 12,599 words is one every 300 words.

would 55-18 / (137-18)

like 65-15 / (132-15; not counting "alike" and "unlike")

hope 29-3 / (56-3)

ere 17-2[Carrier-1819!] (48-2)

dread 11-0 / (24-0)

vision/s 11-1 / (15-1)

brain/s 11-0 / (19-0)

Five shorter poems by Moore yield no hits in Jackson's Table 15.1. Thus, Moore's Old Dobbin gets zero hits from Jackson's rigged list, but one "like" from mine. Another short poem, Moore's To a Young Lady on her Birth-day, yields zero hits from Jackson's six, but two instances of "like" from mine, plus one "Ere" and one "hope," making four hits to Jackson's none. Flowers? Zip for Jackson's, 3 for mine (would 1x and should 2x). Moore's manuscript Valentine for Fanny French contains none from Jackson's list favorite expressions, but one "hope" marks it for Moore. The brief manuscript poem that Jackson refers to as "To Clem" is actually titled To Little Clem. from a little girl according to Mary S. Van Deusen's transcription. Jackson's list offers no help, but Clem yields one "like" from mine. Result: all five short poems that Jackson's list could not identify as Moore's contain at least one of the eight great Moore-markers herein commended. My list beats Jackson's 5/5 times.

Jackson's average being one favorite locution every 129 words, a long poem like Moore's Yellow Fever of 1135 lines should yield nearly 9 hits, but gets only 6. Mine gets

4 likes"Yellow Fever" gets 12/15 or 80% of my expected average; 6/9 or 67% of Jackson's.

1 should

1 hopeful

3 dread

2 visions

1 brain

For The Pig and the Rooster, Jackson's 5-count is only slightly lower than his expected average of 6 for a poem of 783 words. A nice round ten can be expected from mine, which actually yields thirteen: 7 instances of like, 2 hits each for should and would, one ere and one brain.

I've got 9 of 14 expected hits for a poem the size of The Wine Drinker (1069 words); and 14 of expected 15 in The Water Drinker (1131 words); compared with Jackson's better 10/8 for "Wine Drinker" and somewhat worse 5/9 for "Water Drinker."

Among the manuscript poems, Moore's Irish Valentine at 590 words most closely approximates the word-total of 542 in "A Visit from St. Nicholas." "Irish Valentine" should yield between four and five hits from Jackson's list but only gets one. How fares it with mine? Five likes, one brain, and one hope for a solid 7 of my expected 7.6. From Jackson's list two manuscript poems by Clement C. Moore, Caroline's Album and To Eliza, in England get zilch. From mine? should-1, would-3, and like-1 for a total of 5 hits in "Caroline"; and one would for "Eliza," which I guess is better than nothing.

Among longer Moore poems with seemingly too-few hits on Jackson's Table 15.1, Natural Philosophy shows only one hit of 4-5 expected in 590 words. Counts for our great eight: should-2; would-5; like-2; dread-1; a total of 10 when we expected about 8, on average.

How about Moore's misunderstood manuscript poem From Saint Nicholas? Five Moore-markers there (hope-2; would-1; like-2), or four if you don't like "like" as a main verb. And we only needed three to match the expected average for a poem of 214 total words.

In a poem by Clement C. Moore of 542 words, seven occurrences of words from our list of eight great favorite expressions can be expected, on average. The Night Before Christmas has 15; with a frequency rate of 1 in 36 words. A Livingston poem of 542 words (an ambitious, uncomfortable length for Livingston that he almost never attempted) on average would be expected to have not even two (542/300 = 1.81) of these eight words. Less than two, if Livingston's, and "The Night Before Christmas" has--how many? Fifteen!

- 8 likes

- 1 would

- 1 should (Ho ho ho, Poetry Foundation can't handle Moore's distinctively conditional style and replaces Moore's one "should" with "did." Poetry Foundation also revises Moore's "Donder" to "Donner." Don't blame Random House for "did" and "Donner"; neither revision appears in the cited Random House Book of Poetry for Children.)

- 1 hopes (plural and children's, naturally)

- 1 dread (the mature speaker's, overcome by Santa's comical appearance)

- 1 ere

- 1 visions (plural)

- 1 brains (plural)

Acknowledgments

- Many thanks, again, to Mary S. Van Deusen for transcribing and posting unpublished manuscript poems by Clement C. Moore on her magnificent Henry Livingston site.

- Red Holloway (immortal now, formerly of Morro Bay) blows the blazing tenor sax on Hey Santa Claus. Turn it up! For more information in that line, Jazz critic and Clemson professor Robert Campbell has a great page of painstaking discography, all about The Chance label.