For an earlier version by Walt McDougall of his social encounter with Melville at Matt Morgan's studio, see Walt McDougall in the American Mercury

For more thoughts on Melville at Morgan's studio see Matt Morgan on Broadway.

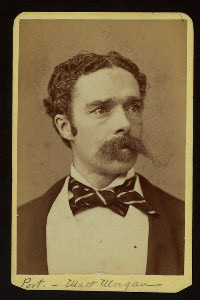

Graphic artist Walt McDougall (1858-1938), as quoted in the newspaper review by George Currie:

Found some great photos of Walt McDougall on Facebook.“Herman Melville, whom I often encountered, as I did Walt Whitman, lounging along Park Row, a rather moody, sullen man, I thought, but now I imagine that he was shy.”

(Brooklyn Daily Eagle, Sunday, February 21, 1926)

Then, taking the hint in the Brooklyn Daily Eagle, I grabbed McDougall's 1926 book This is the Life! in the Hathi Trust Digital Library. Goodness!

<

Recalling old colleagues in chapter three (Living by One's Wits), McDougall reaches way way back to the humor magazine Tomahawk, illustrated by Matt Morgan. McDougall seems to make this Tomahawk a New York affair. He also mentions contributing occasionally to Puck (not Punch), launched in New York on September 27, 1876.

Puck started as a German-language weekly but an English version appeared the following year in March, 1877. --Delaware Art MuseumWas the old London Tomahawk (1867-1870) revived by Morgan in New York, some time in the later 1870's? Or perhaps McDougall is misremembering Morgan's association in New York with Frank Leslie’s Illustrated Newspaper and (even more likely) Frank Leslie’s Budget of Fun.

Leslie hired Morgan in August 1870 to replace the late William Newman (died July 1870). --Yesterday's PapersIn any case, the reminiscence is clearly tied to Matthew Somerville Morgan and Morgan's New York studio, where McDougall claims to have seen Melville one afternoon among a host of others:

Farthest back in my memory is the Tomahawk, started by Matt Morgan, a dashing, handsome Englishman of the Herbert Standing type, whose studio was the daily resort of many of the illustrators, poets and actors of the time. There I first saw Walt Whitman on my only visit to the place with John Bolles, a Newarker. That afternoon there came Thomas [Theodore] Wüst, Hopkins and [Fernando] Miranda, with Charles Frohman, then circulation manager for the Graphic, William H. Shelton, famous for his escape from a Southern prison, and the dapper Gray Parker, then on Harper’s staff, with others no less distinguished but quite unknown to the two obscure Newarkers.

I had almost forgotten to mention among them one whom for many years I did not properly appreciate, Herman Melville, the author of “Typee,” and whom I very often encountered, as I did Walt Whitman, lounging along Park Row, a rather moody, sullen man, I thought, but now I imagine that he was shy. Under the influence of the punch, perhaps, I invited Melville to our house, to meet Marion Harland, and he accepted the invitation graciously enough but he never came.

I remember that both Bolles and I thought the conversation nothing much for such distinguished company, for we were both, no doubt, looking for pyrotechnics. We agreed that we had heard much more brilliant talk right in my own home. I thought Whitman a domineering old windbag who couldn’t keep his tobacco out of his splendid white whiskers, but when I grew up I came to like him very much, and Horace Traubel, whom I knew very well after I went to live in Philadelphia, while he was still a bank clerk, told me that the old poet often urged him to bring me over, but I knew that the secret of his liking was the fact that I was the only man he knew who, like himself, chewed Mayflower tobacco, long since an extinct brand.

In the center of Morgan’s studio was parked a new washtub half filled with claret punch, which, it seemed, was a permanent adjunct of the apartment and which gave me an exalted idea of the owner’s affluence. I remember seeing a similar punch bowl when a child on the occasion of a big baseball game, and, much later, on the dedication, or whatever it was, of Grant’s Tomb.

The Tomahawk was several degrees above the other comic papers in many respects, but it soon died and Morgan returned to London.... (This is the Life! 64-66)Update: For historical background, check out these books available online:

William Murrell, A History of American Graphic Humor (1865-1938);

F. Weitenkampf, American Graphic Art;

J. Brander Matthews on The Comic Periodical Literature of the United States, in Vol. 7 of The American Bibliopolist (1875): 199-201;

and wow! the great recent study by Richard Scully, "Sex, Art, and the Victorian Cartoonist: Matthew Somerville Morgan in Victorian Britain and America," International Journal of Comic Art 13.1 (Spring 2011): 291-325.

Update 2: More on Matt Morgan, from the Twentieth Century Biographical Dictionary of Notable Americans:

and wow! the great recent study by Richard Scully, "Sex, Art, and the Victorian Cartoonist: Matthew Somerville Morgan in Victorian Britain and America," International Journal of Comic Art 13.1 (Spring 2011): 291-325.

Update 2: More on Matt Morgan, from the Twentieth Century Biographical Dictionary of Notable Americans:

MORGAN, Matthew Somerville, artist, was born in London, England, April 27, 1839; son of Matthew and Mary (Somerville) Morgan, both of whom were actors. He was a scene painter in Princess's theatre, London, for a time, and later artist and correspondent of the Illustrated London News in Rome, Italy. He studied art in Paris, Italy and Spain; made a journey into Africa by the French Algeria route in 1858, and served as war correspondent of the Illustrated London News during the Austro-Italian war in 1859. He was proprietor and joint editor of the London Tomahawk, a comic paper, and made a series of cartoons ridiculing the royal family. He was one of the founders of London Fun, and was the principal scene painter at Covent Garden during the run of Italian opera, 1867-69. He came to the United States in 1870 as cartoonist and caricaturist for Frank Leslie's Illustrated Newspaper. He was manager of a theatrical poster lithographic establishment at Cincinnati, Ohio, 1880-85, and organized in Cincinnati the Matt Morgan Art Pottery company in 1883, and the Cincinnati Art Students' league. He returned to New York city and opened a studio as a scene painter and illustrator. He painted pictures for Roman Catholic churches, several panoramic views of the civil war, exhibited in Cincinnati in 1886, and at the time of his death was finishing scenery for Madison Square Garden, New York. He contributed to the exhibitions of the Water-Color society. He published American War Cartoons (1874). He died in New York city, June 2, 1890.So most of Morgan's work "as cartoonist and caricaturist" in America falls within the decade of the 1870's. He returned to New York in the late 1880's, but by then was professionally engaged in a different sphere, "as a scene painter and illustrator." As the reference to Charles Frohman indicates, McDougall's encounter with Melville coincides with his early career at the New York Graphic. Frohman worked in the circulation department at the Graphic from 1874-1877 (Charles Frohman: Manager and Man). Another reason for dating the reminiscence to some time in the mid to late 1870's, when McDougall was about twenty, give or take a couple of years.

--vol 7, ed. Rossiter Johnson

McDougall says he found enough courage in the tub of punch at Morgan's to invite Melville home to meet Marion Harland. And Melville accepted but never showed.

But what does McDougall mean, "lounging along Park Row"?

Related posts at melvilliana:

No comments:

Post a Comment