|

| Bodleian Libraries, Broadside Ballads Online |

Dr. Snodhead, a very learned man, professor of Low Dutch and High German in the college of Santa Claus and St. Pott's.... --Moby-Dick - The Decanter

"As there was no linguistic border between the Netherlands and Germany until the twentieth century, Low German is an important comparandum for the study of Dutch." --Michiel de Vaan, The Dawn of Dutch: Language contact in the Western Low Countries before 1200

Now, in German, one of the few words known to uneducated Americans is blitzen, because it forms part of an oath supposed to be a favorite with Hollanders and the Germans. "Donder-and-blixen" used to stand as a popular and jocose synonym for a Dutchman, very much as in Mexico, at the present day, Englishmen and Americans are gravely called Los God-damés. --The Critic - April 23, 1881

Santa's immediate forebear in America came not from New Amsterdam or New York, but from German settlements in Pennsylvania. --Phyllis Siefker, Santa Claus, Last of the Wild Men

Dutch and German influences linger, too, in the names of the reindeer Donder and Blitzen (Thunder and Lightning).... As for his vision, it is nothing less than the casting of a secularized and dehistoricized icon of prosperity out of the American melting pot's assorted religious and folk traditions. --Janet Gray on Popular Poetry, Encyclopedia of American Poetry: The Nineteenth Century, ed. Eric L. Haralson (Routledge, 1998).

The bastard form "Blixen," neither Dutch nor German.... --MacDonald P. Jackson, Who Wrote "The Night Before Christmas"? 117

Run, run Rudolph: Randolph's way too far behind. --Chuck Berry, Run Rudolph RunIn Author Unknown, Don Foster charged that Clement C. Moore's late preference for "Donder and Blitzen" shows he "did not know the original names of his own Dutch reindeer."

Who could forget Dunder and Blixem? That "Dutch reindeer" line provided one of Foster's best sound bites during his golden years of media celebrity, back before his Funeral Elegy fiasco (Ron Rosenbaum's good word for it in The Shakespeare Wars) became a textbook example of high-profile failure. According to Foster, the perceived inability to write "Dunder and Blixem" (as two of Santa's eight reindeer were named in the 1823 first printing) exposed Moore's ignorance of Dutch and therefore his linguistic incapacity to have written "A Visit from St. Nicholas," aka "'Twas the Night Before Christmas."

Foster went wrong from the jump by not recognizing Moore's handwritten change of "Blixem" to "Blitzen" on the printed Sentinel broadside (held by the Museum of the City of New York) as compelling physical evidence of authorial tinkering with at least one reindeer name.

|

| N. Tuttle. Account of a visit from St. Nicholas, or Santa Claus [Detail]. Museum of the City of New York. 54.331.17 |

Foster's catchy "Dutch reindeer" argument has been revived by MacDonald P. Jackson in Who Wrote "The Night Before Christmas"? Jackson pays even closer attention to contemporary variants than Foster did, but reaches the same conclusion. To his credit, Jackson recognizes as Foster did not that the Troy Sentinel broadside with Moore's revisions evidently served as a copy-text for "A Visit from St. Nicholas" in Moore's 1844 Poems. Nonetheless, Jackson like Foster before him interprets the revision history of reindeer names as tangible evidence for Henry Livingston's authorship of the beloved Christmas classic. How Jackson also went wrong is worth exploring, as a kind of public service to general readers who would never expect so much misinformation and specious reasoning in the published work of an accomplished Shakespeare scholar.

Jackson's first mistake is revealed in his idea that "Dunder and Blixem" in the 1823 Troy Sentinel printing must present an "especially awkward detail for Moore's champions" (Who Wrote, 15).

Using loaded terms like "champions" and "believers" is one way of projecting a false balance, verbally preserving the illusion of equivalency between Moore and Livingston as the two worthiest authorship candidates. They are not equally matched contenders, however, because only Moore claimed authorship, and only Moore published the poem over his name, and only Moore was credited with authorship by knowledgeable contemporaries, including (besides his daughters, the best witnesses of all) such eminent editors and literary critics as Charles King, Charles Fenno Hoffman, William Cullen Bryant, W. A. Jones, John Keese, Evert A. Duyckinck, and Edmund Clarence Stedman. Since numerous verifiable facts corroborate Moore's authorship, and none identifies Henry Livingston, Jr. (who never claimed it anyway) with "A Visit from St. Nicholas," there can be nothing "awkward" presented by any printed text of the poem. The burden of proof has always been on the Livingston side, despite this early attempt by Jackson to shake it off. His authorship controversy or "question" is purely hypothetical. The label "believer" more aptly describes the supporter of a different candidate than Moore. Without evidence, belief in Livingston's authorship of "A Visit from St. Nicholas" is indeed a matter of faith.

To evaluate Jackson's discussion of reindeer names properly, it helps to keep in mind the extent to which the hypothetical authorship question imposes its own agenda. Authorship issues can wait. All kinds of editorial and interpretive problems may be addressed and scrutinized and solved, or not solved, without reference to authorship. Authorship most of the time does not have to be on the table at all. It's only before us here, now, because I'm indulging my own authorship obsession.

We know exactly what happened: the reindeer names "Dunder and Blixem" eventually became "Donder and Blixen" (most notably in The New-York Book of Poetry) and then "Donder and Blitzen" in Moore's 1844 volume of collected Poems. How and why the different versions came to exist are largely matters of conjecture. Some conjectures will be more informed and persuasive than others. Conjectures that require a hypothetical author, someone other than Clement C. Moore, will merit the highest degree of skepticism.

Moore's later revisions of reindeer names supply real, not conjectural evidence of Moore's authorship. If anything, the documented 1837 and 1844 changes suggest that Moore's original preferences may have been altered by one of the copyists referenced in T. W. C. Moore's 1862 letter to the New-York Historical Society. No one disputes the fact that at least two stages of copying preceded the first publication of "A Visit from St. Nicholas" in the Troy Sentinel on December 23, 1823. Maybe "Dunder" and "Blixem" were in Moore's original manuscript, maybe not. Jackson needs it to be "not," and then some. His pro-Livingston argument requires, in addition to the hypothetical existence of a lost exemplar not by Clement C. Moore, authorial spellings Dunder and Blixem therein, as a prerequisite for arguing that the imperfect or near-rhyme of "Blixem" with "Vixen" resembles Livingston's practice and not Moore's, who only did it once. True enough, but in this case once ought to be more than enough, since (Ho ho ho!) the exception Jackson cites occurs in a poem Moore wrote for one of his children in the persona of St. Nicholas:

Good children I always give good things in plentyIt wasn't empty: St Nick left his lovely "Letter" and most likely will be back in a few days, on New Year's Eve. In happier times, Santa was not so organized and predictable as today. Kids might find their stockings full of presents on New Year's Day, since

How sad to have left your stocking quite empty.

Santa Claus comes on New Year's Eve.Lacking comparable manuscript evidence for Livingston's authorship of "The Night Before Christmas," and without evidence that Livingston ever in his life wrote the words dunder or blixem (or vixen, for that matter), Jackson wants a bridge to reach the tempting near-rhymes that do occur in Livingston's extant poetry, in order to press for their relevance. Needing to introduce otherwise irrelevant near-rhymes by Henry Livingston, Jr. as style evidence, Jackson resorts to supposing the very thing to be argued:

"Dunder/Donder and Blixem/Blixum" were clearly the prevailing forms, so it is natural to suppose that the Sentinel in 1823 preserved the original authorial spellings. --Who Wrote "The Night Before Christmas"? page 16.By my count that makes four differently spelled forms (Dunder, Donder, Blixem, Blixum), only two of which can possibly be "authorial" in one verse of "Visit." Two at a time, please, only two at a time! Even if these were "prevailing forms" as Jackson claims, he never bothers to explain why the poet, any poet, should be restricted even hypothetically to the commonest variants. Of a cliche, as will be seen. Since Jackson wants to fashion reindeer names into an argument about authorship, his supposition that "Dunder" and "Blixem" are "authorial spellings" here amounts to begging the question. In view of the documented revision history of reindeer names in "The Night Before Christmas," and the poem's unquestioned transmission history involving two copyists, at least, and the undisputed fact that its first publication in a Troy newspaper was unauthorized by the person who composed it, we need more and better reasons for taking "Dunder" and "Blixem" as "original authorial spellings."

Besides the circular logic that aims to fix "Dunder" and Blixem" as "original authorial spellings," Jackson's treatment of reindeer names is ill-informed on three crucial points:

- Contrary to the partial facts offered by Jackson, references to Dutch "thunder and lightning" in popular Anglo-American literature featured numerous variants of dunder/donder + blixum/blixem, throughout the period under examination, c. 1800-1844. Different forms were promiscuously employed and included the words blixen and blitzen along with blixum and blixem.

- The terms Dutch and German themselves were unstable and for many Americans interchangeable. Our so-called Pennsylvania Dutch are Germans.

It must be remembered, however, that at that period [later 17th century, in colonial Maryland] there was not the same distinction between the terms Dutch and German that there is to-day. In fact, the term German was rarely used, and the appellation Dutchman was indiscriminately applied to the representatives of all the Teutonic races. --The Pennsylvania-German in the Settlement of Maryland (Lancaster, PA., 1914)

The Dutch language fundamentally is German, of course, as is English. "High Dutch" meant German. The German for "German" still is Deutsch. Jackson oversimplifies with unnecessarily rigid categories of Dutch and German that do not reflect their linguistic kinship and historical intermingling. In particular, Jackson's oversimplified view distorts the complicated settlement history of New York State:"From first to last the two major elements, known in the old world as "Deutsch" but differentiated as "Hoch Deutsch" and "Nieder Deutsch," mingled here in colonial America most freely, not only on account of common religious sympathies, but also on account of close similarity of languages."

--Charles Maar on The High Dutch and the Low Dutch in New York 1624-1924 in The Quarterly Journal of the New York State Historical Association Vol. 5, No. 4 (October 1924), pp. 317-329; available via JSTOR. - Jackson underestimates pervasive Dutch influence in the Capital Region of upstate New York including Albany and Troy, the county seat of Rensselaer County. The interchangeability of terms for "thunder" and "lightning," illustrated below with numerous examples, means that anybody might have indifferently or mistakenly written "dunder" for "donder," and/or "blixem" for "blixen." Mainly because of the imperfect rhyme with "Vixen," I think (but don't pretend to know) the 1823 reading "Blixem" was a copyist's or printer's error for Moore's first choice, "Blixen." If Clement C. Moore did not write "Dunder and Blixem" as originally printed in the Troy Sentinel on December 23, 1823, any changes were probably accidental, mistakes of transcription or of printing. But if the change to "Dunder" and "Blixem" resulted from deliberate revision, then Troy (formerly Vanderheyden) was one place that a persnickety editor (or typesetter) might have felt extra-empowered to alter the names of Dutch reindeer in accordance with house style. In any case, it remains certain that in 1844 Moore settled on Donder and Blitzen.

|

| New York American - March 1, 1844 |

One thing he continued to do, well into the forties: write poetry...Patterson's active verbs (contributed, acknowledged) are evidence-based, and may be contrasted with the fantasy that has long circulated among believers in Livingston's authorship of "Visit," that Moore passively "allowed" Charles Fenno Hoffman to publish four poems over his name.

Moore contributed several of his pieces to The New-York Book of Poetry, which appeared in 1837. It was in this volume by native New Yorkers that he first acknowledged his authorship of "A Visit from St. Nicholas." Much of his verse had already been published in newspapers and periodicals. --The Poet of Christmas Eve, 112-113.

When "The New York Book" was about to be published, I was applied to for some contribution to the work. Accordingly, I gave the publisher several pieces, among which was the "Visit from St. Nicholas." It was printed under my name, and has frequently since been republished, in your paper [Editor Charles King's New York American] among others, with my name attached to it. --Clement C. MooreAs he states in this February 27, 1844 letter to Charles King, in 1837 Moore "gave the publisher several pieces" including "A Visit from St. Nicholas." Moore's 1837 contribution might explain, by the way, why in 1844 he would have needed the 1830 broadsheet for a copy-text of "A Visit from St. Nicholas." Perhaps Moore had to use the Sentinel broadsheet when making a copy for the printer of his 1844 Poems because he had previously forwarded a manuscript version of "Visit" for publication along with three other of his poems in the New-York Book of Poetry. Other advantages of using a previously printed version as copy-text: less work of actual, physical writing, since you don't have to copy the whole thing again by hand, and a correspondingly reduced chance of introducing new errors.

Since Moore "gave the publisher" his poem "A Visit from St. Nicholas" in 1837, the reading there of "Donder and Blixen" should be regarded as authorized and approved by Clement C. Moore himself.

Whatever Moore may have originally written, in 1837 he authorized the correction or revision to "Donder and Blixen." In 1844 he again changed "Blixem," this time to "Blitzen." As shown below, blixen and blitzen could be and were used interchangeably in popular literature. Poets and journalists treated blixen and blitzen as variants of the same Dutch word. Jackson's investigation goes bust, before it ever gets started, on the reindeer names Dunder and Blixem. Here and elsewhere, the manufactured authorship dispute obscures other problems that are worthier of attention by literary critics and scholars. How to twist blixem into an argument for Livingston's authorship is not the right question. Here's a better one posed by the revision history, more interesting and legitimately arguable: What if anything did Moore mean in 1844 by changing Blixen to Blitzen?

And now, welcome to the melting pot...

"Donder and blitzen!" (1835)

| From "The Journal of a Student," signed "F." (for Sumner Lincoln Fairfield) North American Magazine - April 1835 |

"My mother said that her grandfather used the "Dunder & Blitzen" as familiarly as some other people say "Great Scott!" etc etc etc!"Donder or Dunder? Either way it was Blitzen that Livingston descendants remembered, not Blixem.

Moreover, Jackson's facts are incomplete and therefore misleading. His examples in Table 3.1 purport to show early usage of blitzen in German contexts. According to Jackson's neat chronology, only later (1843 and after) does the word blitzen occur with Dutch rather than German associations. Well, to be fair Jackson does grant one exception (not counting Scott's Guy Mannering):

"The only precedent for offering Moore's exact "Donder and Blitzen" as Dutch is Almar's of 1836." --Who Wrote The Night Before ChristmasFor the sake of tidiness, apparently, Jackson has omitted telling counter-examples from his published Table 3.1, including instances of blitzen in Guy Mannering (1815) by Sir Walter Scott. (Jackson's

" 'Donder and blitzen! ...' " (1820)And here's something else Jackson missed: in chapter 4 of the first volume, the 1820 Philadelphia edition of Guy Mannering gives "Donder and blitzen!" in early dialogue by the Dutch smuggler, Dirk Hatteraick.

| "Donder and Blitzen" in Scott's Guy Mannering (Philadelphia, 1820) |

Here as in the case of Happy Christmas, Jackson's over-reliance on the LION database (and on Don Foster) gets him into trouble. "Happy Christmas" turns out to have been commonplace, particularly among devout Protestants for whom the "Happy" part implied "Sober"; and blixem was never the regular or "prevailing" English spelling for Dutch "lightning" in popular literature. Along with the fluid usage of variant spellings, what Foster and Jackson both missed is how commonplace the expression was (requiring zero specialized knowledge beyond the ability to read), and how humorous were its usual contexts when employed as a stereotype of the funny Dutchman. Journalists in the 1820's differed about what constitutes true Dutch. Aiming for realistic Dutch dialogue, a political anecdote in the Black Rock [New York] Gazette on November 9, 1826 made it "tunder un blixzen":

Reprinted with the reading "tunder un blizzen" in the Vergennes, Vermont Aurora on November 23, 1826; and "tunder and blizzen" in the Worcester, Massachusetts Eclipse of the Sun on November 29, 1826.

|

| Vermont Aurora - November 23, 1826 |

|

| Carolina Observer (Fayetteville, NC - November 29, 1826 |

- blixzen

- blizzen

- blitzen

Furthermore, usages of blixen rival blixem/blixum all through the first half of the nineteenth century.

1743

... the beastly, unmannerly insinuation that follows—Dunder, Blixen, Tyvel!1781

--The Scots Magazine - November 1743

... In a little time we shall hear what effect the Manifesto has had on the Dutch; for I imagine it came as unexpectedly upon them as us. Donder & Blexin, Fluuckter, &c. will be exclaimations heard every where amongst them. --Letter to the Editor signed "John Roastbeef" in Lloyd's Evening Post, January 5, 1781.Between 1785 and 1799

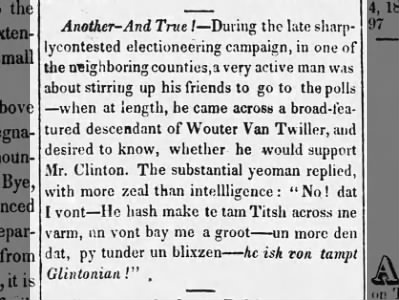

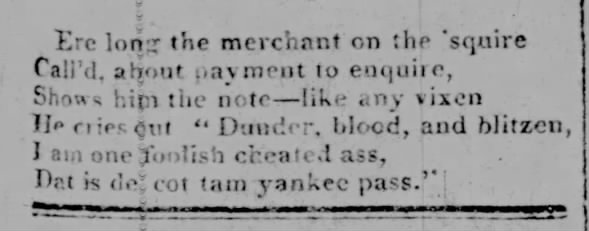

Verse satire issued as a broadside, titled Donder & Blixin: "Attend to my ditty, ye Germans and Dutch...."

|

| Broadside Ballads Online |

Tho' fery creat Men yet he roar'd like a Vixen,

You Scoundrels and Deafsman, ah Donder and Blixin.

By Got, Zur, I say you're the vorst of all foes

You have ruin'd my Face, Zur, you pite of my Nose.

--Donder and Blixin. The Dutch Rubbers, or Bite Your Own Nose.1786

Now stalk'd like a Cyrus the lean dame Van Blixen1793

Whom Scandal has christen'd a paragon'd vixen....

--"Description of a Dutch Ball at the Cape of Good Hope" By Miss Emily Brittle [from The India Guide by Sir George Dallas]. The European Magazine, and London Review, for March 1786; reprinted in the Weekly Museum, August 18, 1792.

"Donder and Blixen, Dutchmens see!"1799

--Opening line of The Sans Culottes, and the Grand Culottes, a musical portraying "the principal Events during the Invasion of Holland." Reviewed in The Public Advertiser, April 16, 1793; quoted in Paul F. Rice, British Music and the French Revolution (Newcastle upon Tyne: Cambridge Scholars Publishing, 2010), page 220.

Oh Hell! and dunder and blixen!

--"For the Centinel / An Acrostic" [DOCTOR IOHN VAN BLUSTER]; Newark, New Jersey Centinel of Freedom, March 12, 1799.

As I find der ish no DONDER AND BLIKSUM in de English Dikshonere I hope youl put both in yours to oblige a Subscrybur1809

HANS BUBBLEBLOWER. --Philadelphia Gazette of the United States, June 12, 1800

From A History of New York by Diedrich Knickerbocker (Washington Irving):

1810"Dunder and blixum! swore the Dutchmen."

I endeavored to appease the enraged Dutchman in vain. He told me it was the same dueifels kint that had insulted his master, and clenching his fist swore with a tremendous dunder and blixen that he would have satisfaction….1824

--Francis Fungus "To Christopher Caustic, Esq. Apothecary, &c." Philadelphia Repertory, September 1, 1810

"Donner and Blitzen," exclaimed she.... --Dame Van Dam, Dutch wife of Mynheer Van Dam in "Job Cook--A Legend," The Atlantic Magazine, July 1824.

[blixum as "German"] ... while an old German, who was sitting against the capstan with his pipe in his mouth, grumbled out--"Dunder and blixum, you've broke mine pipe mit your nonsense!" --"Ten Days in the Country," New York Spectator, August 31, 18241825

In Reading, Pennsylvania they call Santa's Dutch reindeer Dunder and Blixen.

|

| Berks and Schuylkill Journal [Reading, PA] December 31, 1825 |

In Philadelphia, Santa's Dutch reindeer are re-named Dunter and Blixen...

| The Casket - February 1826 |

In "The Barber of Gottingen," by Robert Macnish, widely reprinted from the October 1826 number of Blackwood's Edinburgh Magazine,

the barber's fiendish customer (short and "burly" like the stereotypical Dutchman, and dressed accordingly with broad-brimmed hat and trousers with buckles at the knees) shouts both "Donner and blitzen!" and

"Dunder and blixum!" Reprinted widely, for example in the New-York American, November 24, 1826, Macnish's "Barber" influenced Poe's The Devil in the Belfry with its "Donder and Blitzen" (listed and dated 1840 in Jackson's Table 3.1, although not identified there by story title).

1827

1828

Fri, Jul 20, 1832 – 3 · Sentinel and Democrat (Burlington, Vermont) · Newspapers.com

Fri, Jul 20, 1832 – 3 · Sentinel and Democrat (Burlington, Vermont) · Newspapers.com

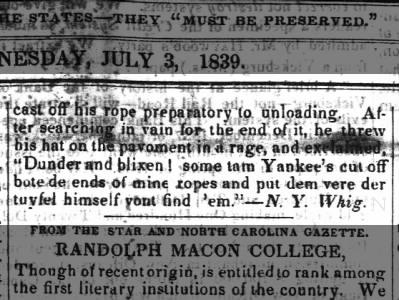

As demonstrated by the examples above, "blixen" appears repeatedly in newspapers and magazines c. 1800-1844, usually with "dunder" but sometimes "donder." Below, a relevant and suggestive instance from the verse burlesque titled "A Yankee Pass," where "blixen" rhymes with "vixen":

Other versions print "A Yankee Pass" with the end-rhyme blixen changed to blitzen:

· Fri, Nov 2, 1827 – 1 · Pensacola Gazette (Pensacola, Florida) · Newspapers.com

· Fri, Nov 2, 1827 – 1 · Pensacola Gazette (Pensacola, Florida) · Newspapers.com

These printed versions of "A Yankee Pass" show that as early as 1827, blitzen could and did replace blixen as a rhyme for vixen in popular American verse about a Dutchman.

1827

… A Dutchman who stood by listening to the conversation, seemed much astonished at what he heard, and throwing his hat on the ground, and clenching his hair with both hands, exclaimed, "Donner and blitzen! If I go id that boat I hold my hair tight!"In The Spirit of the Old Dominion (Richmond, 1827), Stephen T. Mitchell's "worthy Dutchman" Carle van Fraunk "swore by 'Donner and Blitzen'":

--"New Steamboat" anecdote in The Ariel [Natchez, Mississippi] for March 9, 1827

| The Spirit of the Old Dominion (1827) by Stephen T. Mitchell |

[Fourth of July toasts in Milledgeville, Georgia]

By James S. Calhoun…. The Dutchman's answer to the enquiry, what are the most attractively beautiful natural objects: "Donder unt blitzden mon, dem dare dings wat var de peddigoats and abrons." -- Southern Recorder, July 12, 1828; reprinted in the Georgia Journal, July 14, 18281829

"Donner and blitzen" merely a prelude to "true Dutch wrath":

1830'Donner and blitzen,' or 'tousand deyvils,' were too mild words to act as safety-valves to Martin's wrath, and after a vain attempt to give utterance to his feelings, he fairly turned Andrew out of the house, and that too in no very courteous style. After this explosion of true Dutch wrath, (which is rather slow to be started, but always means something when it does come,) Martin was unsociable, testy and uneasy....

Indiana Palladiuim (Lawrenceburg, IN) - May 23, 1829

--"A Legend of the Law / Martin Van Deinster," excerpted from The New England Galaxy (Boston, Massachusetts) in the Indiana Palladium on May 23, 1829.

D. [Dutchman] Ash?? Do you gall me ash, and do you say I am grazy? Dunder and blixen! --Skillman's New-York Police Reports1832

"Dunder and blixen," roared one of the party--a Dutchman--dey pe noting put de fox grape! --"The Yankee and The Grape-Vines" from the New York Constellation; frequently reprinted, for example in the Haverhill [Massachusetts] Gazette, February 25, 1832; and Miller's Weekly Messenger [Pendleton, South Carolina], March 21, 1832.

Fri, Jul 20, 1832 – 3 · Sentinel and Democrat (Burlington, Vermont) · Newspapers.com

Fri, Jul 20, 1832 – 3 · Sentinel and Democrat (Burlington, Vermont) · Newspapers.com

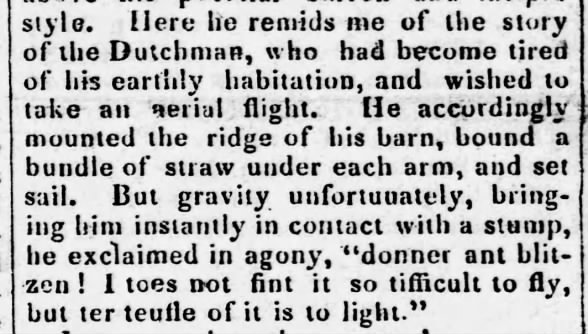

... the story of the Dutchman, who had become tired of his earthly habitation, and wished to take an aerial flight. He accordingly mounted the ridge of his barn, bound a bundle of straw under each arm, and set sail. But gravity unfortunately, bringing him instantly in contact with a stump, he exclaimed in agony, "donner ant blitzen! I toes not fint it so tifficult to fly, but ter teufle of it is to light." --Burlington, Vermont Sentinel and Democrat, July 20, 1832.1833

Hans Schlaffigkopf the hero of "The Astounded Dutchman" swears by "Donner and blitzen" and "Santa Claus":The king of the Dutch, like a very great vixen,

Scolds & swears by the powers of 'donner & blitzen' --Carrier's Address, Canton, Ohio Repository, January 4, 1833

|

| Dedham Patriot (Dedham, Massachusetts) January 11, 1833 |

"Donner and blitzen! Yasu Chrst! Santa Claus! De Tyfel and all! vat ish dat for a shmoke comin de riffer up? Vrouw! Vrouw! come here aus! De riffer is all on a fire!" --as reprinted from the New York Constellation in the Dedham, Massachusetts Patriot on January 11, 1833.

"Dunder und blitzen, said their magistrates..." --"The Red Satchel" in Atkinson's Casket, September 1833 ("From the Saturday Evening Post")

"Dunder and blitzen! exclaimed Johannes [Puterbaugh, "Dutch" patriarch of Rock-Hollow]...." --Cincinnati Mirror, and Western Gazette of Literature - October 5, 1833The 1833 Anecdote of Two Dutchmen, widely reprinted in American newspapers and magazines from Chambers' Edinburgh Journal, gives "Dunder and blitzen" (alternatively, blizen in the Schenectady, New York Cabinet, April 3, 1833) as typically Dutch.

Found on Newspapers.com

1834"Dunder & Blixen" in Gloucester, Mass:

|

| Gloucester [Massachusetts] Telegraph - January 8, 1834 |

…where's Naso Tremaine, my plebe? Demme if he shan't taste of 4th July in the shape of a genteel swig of donder and blixen just from Amsterdam, and out of a brown Dutch jug. --"Arthur Tremaine" in the Military and Naval Magazine of the United States, July 1834Found on Newspapers.com powered by Newspapers.com

|

| Weekly Standard [Raleigh, North Carolina] - July 3, 1839 |

|

| Greensboro Patriot - May 11, 1841 |

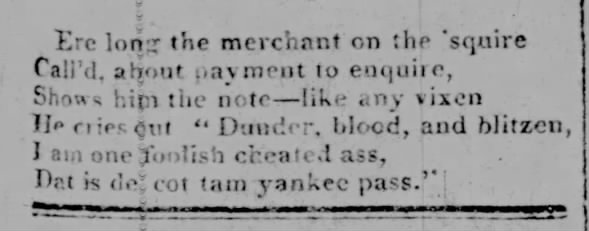

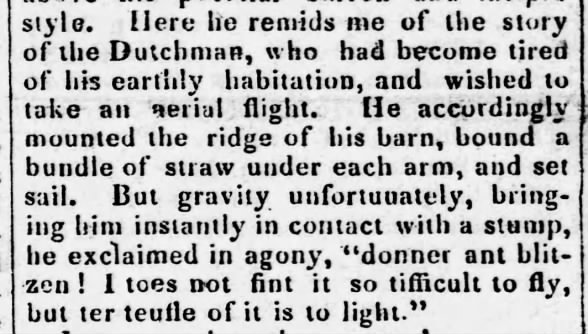

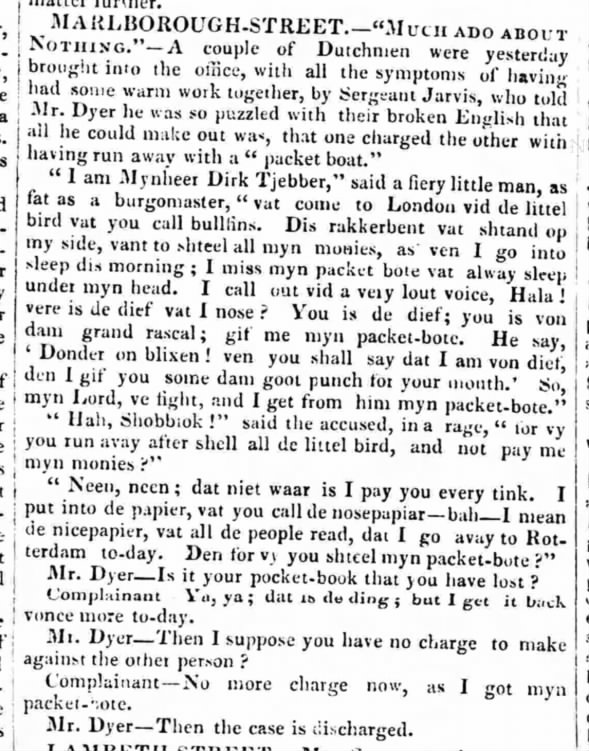

Ere long the merchant on the 'Squire

Call'd about payment to inquire,

Shows him the note--like any vixen,

He cries out "dunder, blood and blixen;

I bees won foolish, cheated ass;

Dat be de Got tam Yankee pass."

--New England Galaxy via The Weekly Miners' Journal [Pottsville Pennsylvania], April 15, 1826

|

| Weekly Miners' Journal (Pottsville, Pennsylvania) - April 15, 1826 |

Shows him the note--like any vixenHe cries out, "Dunder, blood, and blitzen,I am one fooolish cheated ass,Dat is de cot tam yankee pass."

--Richmond Whig via Salem [Massachusetts] Gazette, June 17, 1828

· Fri, Nov 2, 1827 – 1 · Pensacola Gazette (Pensacola, Florida) · Newspapers.com

· Fri, Nov 2, 1827 – 1 · Pensacola Gazette (Pensacola, Florida) · Newspapers.com

These printed versions of "A Yankee Pass" show that as early as 1827, blitzen could and did replace blixen as a rhyme for vixen in popular American verse about a Dutchman.

1835

· Thu, Jun 4, 1835 – 7 · The Morning Post (London, Greater London, England) · Newspapers.com

· Thu, Jun 4, 1835 – 7 · The Morning Post (London, Greater London, England) · Newspapers.com

· Fri, Jun 12, 1835 – 3 · Liverpool Mercury, etc. (Liverpool, Merseyside, England) · Newspapers.com

· Fri, Jun 12, 1835 – 3 · Liverpool Mercury, etc. (Liverpool, Merseyside, England) · Newspapers.com

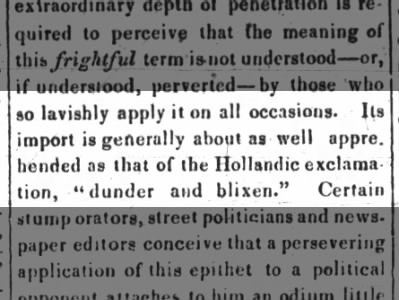

As shown in the warm-up post on A Dutch Quarrel, British newspaper editors in 1835 likewise treated blixen and blitzen as variant spellings of the same Dutch word. The London story, originally titled "Much Ado about Nothing," circulated with alternative forms for the stereotypical Dutch oath, including "Donder on Blixen!" in the London Morning Post, June 4, 1835 and Liverpool Mercury, June 12, 1835; but "Donder and Blitzen!" in the London Examiner on June 7, 1835:

· Sun, Jun 7, 1835 – 11 · The Examiner (London, Greater London, England) · Newspapers.com

· Sun, Jun 7, 1835 – 11 · The Examiner (London, Greater London, England) · Newspapers.com

1837

Several Dutchmen were laboring in the field below. A sand-bag bursting to pieces as it struck the earth near them, caused them to raise their eyes, and a shout of "Dunder and Blitzen!" as they saw the teefle, as they verily believed, making a stoop directly upon them. --"Clayton the Aeronaut," signed "P." in the Boston Transcript via The New York Commercial Advertiser, June 30, 1837"Dutchmen" say "Dunder and Blitzen!" per Thomas Chandler Haliburton in The Clockmaker; or The Sayings and Doings of Samuel Slick, of Slickville.

Martin Van Buren "like the little dogged Dutch boy at school at Kinderhook" says "Dunder and Blixen" to Clay and Webster (New York Herald, December 7, 1837).

|

| New York Herald - December 7, 1837 |

Donner and blitzen! exclaimed the bewildered cobbler [Jacob Kats, Dutch "Cobbler of Dort"], as he took the pipe out of his mouth.... --Plattsburgh Republican, March 9, 18391840

| |

| New York Evening Post - April 7, 1840 |

"Nothing more profane than donder en blixem should be heard. A Dutchman knows no more wicked oath...." --New York Evening Post, April 7, 1840

|

| Columbia Democrat [Bloomsburg, Pennsylvania] - May 2, 1840 |

"Nothing more profane than donder and blixen should be heard. A Dutchman knows no more wicked oath...." --Columbia Democrat, May 2, 18401841

Over the pseudonym "Verbum Sapienti," the writer of a letter to the editor of the Richmond Whig alluded to the commonplace expression "dunder and blixen" by way of correcting another writer's supposed error in using it. For the Richmond linguist, the most proper "Dutch" forms of the familiar oath were not dunder/donder and blixem/blixum but "donner and blitzen":

[there are] no such words in Dutch as "dunder and blixen," which he meant, I presume, for the vulgar oath in that language of "donner and blitzen."As late as 1851, we find Herman Melville indiscriminately lumping Dutch and Germans together as one nation of sailors. In chapter 81 of Moby-Dick, the Pequod meets and then competes for sperm whales against the heretofore unsuccessful Jungfrau or "Virgin." In the heat of the chase, Stubb refers to the Jungfrau captained by Derick De Deer as both a "Yarman" (German) and "unmannerly Dutch dogger." As another such personified confusion of Dutch and German stereotypes, Melville's Dr. Snodhead would relish the looseness and fluidity of Stubb's categories.

--Richmond Whig, April 20, 1841

As I have urged the WHY of Blitzen as a more fruitful question than WHO (you know who), let me end with three very arguable answers. Why did Clement C. Moore in 1844 choose Blitzen over Blixem, and Blixen?

- Moore the over-committed and classically absent-minded professor simply forgot about his previously approved change to "Blixen" and wrote "Blitzen" instead. With the 1830 Sentinel broadsheet before him, the important thing to Moore in 1844 was fixing the imperfect rhyme by revising "Blixem." Blixen and Blitzen were interchangeable rhymes for "Vixen," as the different versions of "A Yankee Pass" in 1826-8 demonstrate.

- Moore the Super-Dad and Responsible Family Man was forever haunted by James Kirke Paulding's off-hand dismissal of "blixum" as "little better than swearing." Thinking of the children, Moore hoped against hope that Blitzen would vary the familiar curse just enough to hide it from his kids, and posterity.

- Moore the myth-maker and linguist extraordinaire wanted to honor Old World Christmas traditions along with his specifically Dutch Saint. Dutch reindeer? Humbug! Moore's reindeer are who we thought they were, Finns. Dolf and Bärtyly don't jingle so well with Prancer and Vixen, but Blitzen inches closer to the hardy Nordic spirit we're always looking for around the holidays. Despite (rather than in keeping with) the popular notion of Blitzen as Dutch, Moore finally and expertly linked his Nordic reindeer with Christmas trees and other more broadly Germanic rites of December. In so doing, Moore honored the German heritage of his intimate friend Dr. Francis:

—to whom the New Year's festival, as characteristic of his father's Nuremberg home as of Dutch hospitality, and his old friend Clement Moore's household rhymes of Santa Claus, with the annual schnapps and pipes of this local saint, brought such genial inspiration.... --Henry T. Tuckerman, biographical introduction to Old New York by John Wakefield Francis.

Related posts:

- Champ Prevails, review of The Fight for "The Night"

https://melvilliana.blogspot.com/2023/12/champ-prevails-experts-foiled-truth.html

- Now, Dasher! in 1826

https://melvilliana.blogspot.com/2019/12/now-dasher-in-1826.html

- How we know Clement C Moore wrote The Night Before Christmas

http://melvilliana.blogspot.com/2017/05/how-we-know-that-clement-c-moore-wrote.html

- Key witness letter by Livingston cousin TWC Moore http://melvilliana.blogspot.com/2018/02/key-witness-letter-by-livingston-cousin.html

- Livingston cousin T. W. C. Moore

http://melvilliana.blogspot.com/2018/12/livingston-cousin-t-w-c-moore.html

- Computer error, please try again

http://melvilliana.blogspot.com/2016/11/computer-error-please-try-again.html

- Eight great favorite expressions of Clement C Moore

http://melvilliana.blogspot.com/2017/04/eight-great-favorite-expressions-of.html

- First printing of A Visit from St Nicholas

https://melvilliana.blogspot.com/2019/04/first-printing-of-visit-from-st-nicholas.html

- Lines written after a snow-storm, 1824 and 1844 versions

https://melvilliana.blogspot.com/2019/04/lines-written-after-snow-storm-by.html

Backhanded reference to German philologist, August Friedrich Pott?

ReplyDeleteMelville's next book Pierre features a comparable bit of fun with German, with similar use of bathos. One of several ridiculously grand titles for an imaginary German prince is "Heir Apparent to the Bankrupt Bakery of Fletz and Flitz." It's like the fall from high to low in M-D, Saint to Pott.

Delete