|

| Ashley Lake Loop Trail - Photo by Kimberly Kaigle |

interrupting the flattered author who sat thoughtful on a hay tuft—with such phrases as “great” “glorious” “by Jove that’s tremendous” &c.

--Evert A. Duyckinck, letter to his wife Margaret dated August 8, 1851; as quoted in Luther Stearns Mansfield, Glimpses of Herman Melville's Life in Pittsfield, American Literature (March 1937) pages 39-40.

"His memory on Onota's shore,Only that, and nothing more!" --Souvenir Verse and Story

Mrs M had a poet in the company and his poem too a stout MSS of heroic measure, a glorification of the United States in particular with a polite slanging of all other nations in general . . . which H M read with emphasis (interrupting the flattered author who sat thoughtful on a hay tuft--with such phrases as "great glorious" "By Jove, that's tremendous" &c)--but perhaps the most noticeable incident was a gathering of the exiled fowls in a corner who cackled a series of noisy resolutions, levelled at the party. "Turn em out!" was the cry. The author impelled by the honor of his poem charged fearlessly, scattered the critics of the pit, clasping the most obstinate bodily and "rushing" her a rapid descent below." (page xvii)As a graduate student on a mission from Hershel Parker, Olsen-Smith re-examined the manuscript at NYPL and corrected one earlier misreading in the passage above. According to Duyckinck the unruly hens were really "critics of the pit" not "cuties of the pit" as Mansfield and Leyda erroneously had it. Duyckinck pictured those evicted chickens as noisy critics, jeering like the groundlings in Shakespeare's day.

For the holiday, John C. Hoadley pronounces a newly composed poem, "The Union" [later retitled "Destiny"] --The Melville Log Volume 1 - [416]

Leyda's source for this information, cited in volume 2 of the Melville Log, is a manuscript by Hoadley in the New York Public Library Gansevoort-Lansing collection. Looking specifically for Hoadley's 1851 poem "The Union," re-titled "Destiny" according to Jay Leyda, I have contacted NYPL to request more information about Hoadley manuscripts in the Gansevoort-Lansing collection, Box 351. If NYPL has Hoadley's poem THE UNION aka DESTINY and can provide scans, I hope to transcribe the text on Melvilliana.

Corroborative evidence for Melville's reading of John C. Hoadley's "Union" poem exists in the letter Hoadley wrote to Evert Duyckinck on September 9, 1851. I located this item years ago, as reported in the 2016 Melvilliana post

- Melville's hearty praises for Hoadley's poem The Union

https://melvilliana.blogspot.com/2016/09/melvilles-hearty-praises-for-john-c.html

Pittsfield, Sept. 9th. 1851.

E. A. Duyckinck Esq.

Dear Sir,

I received a copy of the Literary World a few days since, containing an interesting account of your excursion to Grey Lock, for which I suppose I have to thank your kindness. I read it with lively pleasure though not without a twinge of selfish regret that I could not be of your party.— "Can a man hold fire in his hand by thinking on the frosty Caucasus?”

The Harpers, to whom I had sent my national poem for publication, decline it, and advise me to send it to D. Appleton & Co. which I have accordingly requested the Messers H. to do.— I can not but desire to have it printed, but have not much hope of it. Melville’s hearty praises give me more hope than anything else.

I am, My Dear Sir,

Very Respectfully,

Yours &c. John C. Hoadley.

Citation:

Manuscripts and Archives Division, The New York Public Library. "Hoadley, John Chipman (1818-1886)" The New York Public Library Digital Collections. 1851. https://digitalcollections.nypl.org/items/d9236f50-693b-0133-a932-00505686d14e

* I am indebted for this Chapter to the kindness of a much esteemed and very clever friend. -- Taghconic chapter 6, Berry Pond.

The author impelled by the honor of his poem charged fearlessly, scattered the critics of the pit, clasping the most obstinate bodily and "rushing" her a rapid descent below. This was the ludicrous side. On the other, the Poet was a thoughtful sensible man and was our pilot to the Ashley Pond or Washington Lake which we reached at last after an endless ascent by the side of steep gorges, on the summit of the Hoosac, looking back to the distant sublimities of cloud & mountain of the Taghconic. -- Melville in His Own Time, page 58

The "Poet" turned "pilot" confidently guided Duyckinck and company to Ashley Pond, a location that Hoadley knew exceptionally well, for the best professional and civic reasons.

As an engineer and engaged citizen of Pittsfield, John C. Hoadley worked hard to bring good water to Pittsfield. Hoadley

was very active in all the efforts to acquire Ashley Lake for water supply and at a public meeting a vote was passed “thanking Messrs. McKay and Hoadley for their public spirited efforts in behalf of supplying the village with pure water." -- Joseph Ward Lewis, quoting Smith's History of Pittsfield page 563 in "Berkshire Men of Worth," Berkshire County Eagle, September 18, 1935.For Hoadley that work began the previous year with his formal report in September 1850 to the Pittsfield Library Association. Presumably the firm of McKay & Hoadley would have been of service in the manufacture and supply of necessary iron pipes. As the town expert, or one of them, Hoadley was assigned to the water-works committee. Coincidentally, the guided trip to Ashley Pond described by Duyckinck in August 1851 might have provided Hoadley with a great opportunity for obtaining another water sample. Regular samples were then being collected for testing by Hoadley's committee, expressly appointed "to make a thorough examination of the quantity and quality of the water of Lake Ashley."

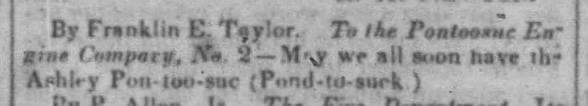

At the big Firemen's banquet or supper or levee on January 15, 1851, reportedly attended by 200 guests, Hoadley spoke at some length on "the great subject of water," specifically the merits of Ashley water:

“The great subject of water, which is exciting a great deal of interest in town just now, is one upon which we have all to form opinions that shall guide us in immediate action, and it is important that we should form wise opinions. About the excellence of the water of Lake Ashley, about its desirableness in our village, I think sir there can be but one opinion. --Pittsfield Sun, January 23, 1851

Knowing Hoadley and his hobby, some in the audience could not have been too surprised by his closing revelation:

"This water in our glasses is from lake Ashley. It came down by the ambulatory aqueduct, the circulating aqueduct not being yet in operation.

Concerning the obvious desirableness of pure drinking water from Ashley, Franklin E. Taylor concurred in this toast To the Pontoosuc Engine Company, No. 2:

"May we all soon have the Ashley Pon-too-suc (Pond-to-suck)."

Related posts:

- Refresher on heroic measure

https://melvilliana.blogspot.com/2021/07/refresher-on-heroic-measure.html

- Definitely Destiny

https://melvilliana.blogspot.com/2021/07/definitely-destiny.html

- Destiny: a poem by John C Hoadley 648 lines plus endnotes, transcribed here

https://melvilliana.blogspot.com/2021/07/destiny-poem-by-john-c-hoadley.html

- Why On Onota's Graceful Shore can't be the one

https://melvilliana.blogspot.com/2024/05/why-on-onotas-graceful-shore-cant-be.html

- Examples of polite slanging in Hoadley's Destiny

https://melvilliana.blogspot.com/2024/05/examples-of-polite-slanging-in-hoadleys.html

Meredith Mann, Librarian for Manuscripts, Archives, and Rare Books at The New York Public Library has kindly informed me that "this poem, in box 351 of the Gansevoort-Lansing collection under the title "Destiny," is written within a bound volume on 53 sheets, some sheets with manuscript additions or drawings on their versos. It is mostly written in ink, with some pencil notations." Copies ordered!

ReplyDelete