The "most talked about" and "much hooted-at" review of Omoo in Blackwood's Edinburgh Magazine, as Hershel Parker frames it in Herman Melville: A Biography Volume 1, 1819-1851 (Johns Hopkins University Press, 1996) at pages 520 and 533, elicited more editorial hooting in the New York True Sun for June 30, 1847. The True Sun, founded by rebellious exiles from the New York Sun, had favorably noticed Omoo on May 1, 1847; this earlier notice of Omoo is reprinted in Herman Melville: The Contemporary Reviews, edited by Brian Higgins and Hershel Parker (Cambridge University Press, 1995) at page 98. Transcribed below, the later commentary in The True Sun on the "book-worm sagacity" and British "superciliousness" exemplified in Blackwood's review of Omoo is not previously recorded in Melville scholarship.

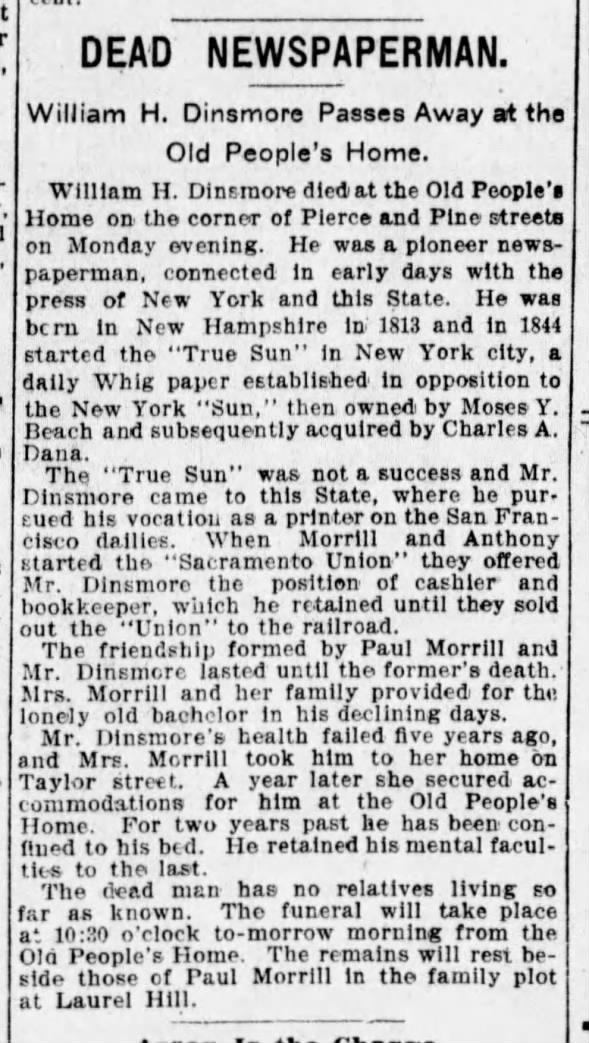

The True Sun was then owned and edited by William H. Dinsmore and Paul Morrill. What most amused these and other journalists in New York State (along with family and friends of the author) was the British reviewer's suspicion that "Herman Melville" might be a fake name.

YANKEE BOOKS AND ENGLISH CRITICS.— The question “who reads an American book?” seems to have been solved of late, and even Blackwood confesses the “soft impeachment.” The last number of that celebrated periodical has not only condescended to notice favorably the two books of Herman Melville, Esq., Typee and Omoo, but to give its readers some extracts. The venerable Reviewer is, however, evidently puzzled to account for the fact that what it calls an “excellent” book, “quite first rate,” should have been written by an American, and that American a sailor. The first difficulty encountered in the matter, seems to be to understand what a sailor is. It is assumed off hand, that the hands in an American vessel are on a par with the miserable outcasts that the state of society in England exudes into the forecastles of English vessels. If such were the case, Mr. Ricardo would never have asked for a Parliamentary committee to inquire into the causes of the superiority of American over English shipping, nor would that committee have elicited evidence to the fact that it was owing to the “superior class of men in American ships.” A large portion of the young seamen in United States vessels, are well educated and “gentlemanly” youths, whose interest, enterprise, and love of adventure carry them to sea. We remember some years since, a young gentleman in an eastern city, guilty of some youthful folly, was, on a consultation of friends, to be sent to sea as a punishment. His employer, an old and experienced merchant, objected: “It is,” said he, “with the utmost difficulty that our sons can now be kept out of the forecastle, and if their desires are to be gratified in consequence of misdemeanors, not a clerk will be left in the computing houses. Send him rather on a farm.” This was wisdom. There are very few wealthy merchants and eminent men, who have not, at some period of their lives, experienced

"—How hard it is to climb

Up a slushed topmast, in the summer time.”

All this is utterly incomprehensible to English aristocratic notions; and Mr. Melville was one of them it appears, and his adventures resulted in the volumes, the excellence of which throw doubt in English minds upon the identity of the author. The wonderful book-worm sagacity of Blackwood stumbles over the name “Herman Melville,” and the more readily, that an old novel fans the suspicion:“Our misgivings begin with the title page, ‘Lovel or Belville,’ says the laird of Monkbarns, "are just the names which youngsters are apt to assume on such occasions, and Herman Melville sounds to us vastly like the harmonious and carefully selected appellation of an imaginary hero of romance.”This is a specimon of what is called “knowing too much.” John Bull is not to be “done” by any such humbug as calling sailors “Herman Melville.” We wonder, however, that such an astonishing acuteness did not stumble over the name of “Gansevoort Melville,” United States Secretary of Legation to the Court of St. James, and as Eddie O’Chiltreee remarked of Monkbarns, “put that and that together,” and “smell a rat.” Considering the usual superciliousness of English writers in regard to American affairs, it is not to be wondered that the acute critic should be surprised at a “Dutch patronymic” among a people exclusively Dutch descendants, nor that the fame of Herman Gansevoort, Esq. Should not have penetrated into the obscurity of an English editorial sanctum. The facts are, however, calculated to increase the astonishment of bewildered Blackwood. Herman Gansevoort, Esq. Has clearly divided his name between his nephews, the brothers Melville, of whom Gansevoort represented his country at the Court of Victoria. The other, while pursuing his adventures as a sailor, earned that literary reputation which has led to the question of his identity.

“Of the existence of ‘Uncle Gansevoort of Gansevoort, Saratoga county,’ we are wholly incredulous,” “until certificates of his corporality shall set down the gentleman with the Dutch patronymic as a member of an imaginary clan."

In all this the English reviewers, when they have studied out the facts so as to comprehend them, will have a most practical lesson upon American character and the working of republican institutions. All ranks and grades of society are open to the resistless enterprise and untiring genius of the American character, and it is very unsafe when a boy is seen going into the forecastle of an American vessel as a “green hand,” to predict anything in relation to him. In the case of an English boy under similar circumstances in England, you may safely assert that he is taking up his abode for life—that he is to live a miserable and oppressed being and die in poverty and want. Of the American you may feel confident that he is only seeking an outlet for the fire within, and that because he begins by “slushing a topmast,” “furling a royal” or “taking in the slack of the topsail halyard,” it is by no means safe to aver that he will not speedily astonish the literati of Europe in the line of their own occupations; that he will not revolutionize the first country he lands in, or suddenly turn up member of Congress from some western State. All these practical effects of republican energy and genius, English writers and politicians have yet to “get through their hair.”

-- The True Sun (New York, NY) June 30, 1847; found on Genealogy Bank.

Titled "Pacific Rovings" the review of Omoo appeared in Blackwood's Edinburgh Magazine for June 1847 at pages 754-767; reprinted in Littell's Living Age on July 24, 1847.

07 Mar 1900, Wed The San Francisco Examiner (San Francisco, California) Newspapers.com

07 Mar 1900, Wed The San Francisco Examiner (San Francisco, California) Newspapers.com

No comments:

Post a Comment