"... all the special pleading of a literary devil's advocate cannot prevent a writer of genius from assuming his appropriate place among the auctores classici of his nation and tongue."

|

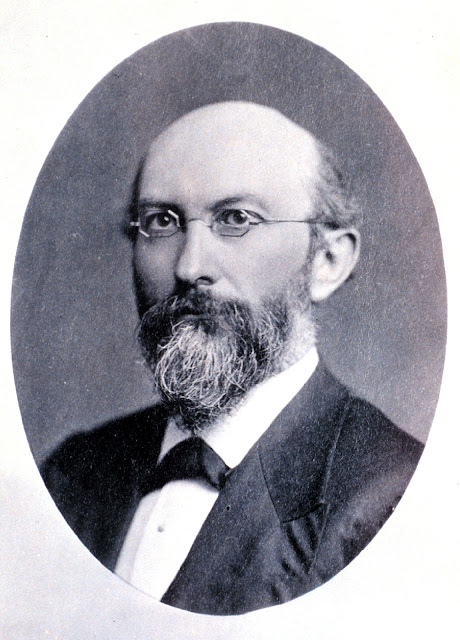

| Dr. James C. Welling via National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration - U. S. Department of Commerce |

Welling's authorship of "Notes on New Books" after the departure of former literary editor Edward William Johnston (in April 1851, if not earlier) was confirmed in a public statement by owner-editor William Winston Seaton that originally appeared under the heading "EDITORIAL ANNOUNCEMENT" in the National Intelligencer on August 30, 1860. News of Welling's appointment circulated North and South, often with reference to his authorship of "Notes on New Books," as in this extract from Seaton's original statement, reprinted in the Charleston, SC Daily Courier on September 3, 1860:

.png) |

| Charleston Courier - September 3, 1860 via genealogybank.com |

National Intelligencer.-- W. W. SEATON, Esq., the venerable survivor of the DAMON and PYTHIAS partnership of GALES & SEATON, announces the connection of JAMES C. WELLING with the editorship of the Intelligencer. Mr. WELLING is thus introduced:

Mr. Welling is no stranger in the columns of the Intelligencer, having been, in different capacities, connected with it for the last ten years, during the first five of which, after the retirement of the accomplished Edward William Johnston from the Literary department of the paper, Mr. Welling had charge of it, and was the author of those "Notes on New Books," which, by the scholarship and ability evinced in their composition, would, of themselves, be a sufficient evidence of the qualifications he brings to the tasks of journalism. But it is just to add that during the last five years he has participated in all the duties incident to the editorship of this journal, and has thus served a noviciate quite long enough to give full proof of his vocation to the exacting career upon which he has entered. Enjoying during this period, in the fullest degree, the confidence of my late lamented colleague, Mr. Gales, he has equally, by his high moral and conscientious character, no less than by his rare attainments, merited my own, and I avail myself of his temporary absence from Washington to make this announcement to the patrons whom it is the honor of the Intelligencer to address.

Most likely penned by James C. Welling, the complete review of Moby-Dick is transcribed below from the Washington Daily National Intelligencer of December 16, 1851.

NOTES ON NEW BOOKS.

MOBY DICK: or the Whale. By HERMAN MELVILLE, author of "Typee," "Omoo," "Redburn," "Mardi," "White Jacket." New York: Harper & Brothers.

After a saint has been dead and buried long enough, that is, after his foibles and venial peccadilloes have been almost forgotten, and when accordingly it is proposed to affix his name to the long list of kindred worthies enrolled on the calendar, his pretensions to such canonization, it is well known, must be previously submitted to the ecclesiastical adjudication of the apostolic camarilla; and, still further to guard against the great scandal which might arise from the precipitate bestowal of this saintly investiture on personages whose lives have won for them an unenviable celebrity, and the symmetry of whose character has been marred by any one of the seven deadly sins, the merits and claims of every plaintiff for sainthood are subjected to inquisitorial post mortem examination, much as the Egyptians were wont to do before they would allow the defunct a burial ticket, save that the camarilla buries first and examines afterwards; for we shrewdly suspect that a few of the titled "saints" would never have attained their worshipful dignity if they had not been previously reduced to that condition which enables poets and fish, according to Peter Pindar, to shine with a lustre all their own. Now, in order that the plea for canonization may proceed after due process of law, an officer is attached to the apostolic chamber, known under the complimentary cognomen of the Devil's Advocate, whose duty it is, indeed, in the behoof of the commonwealth of Tartarus, to regard himself as a regularly licensed attorney-general of his satanic majesty, and whose function it is to rake, scrape, and collect all that can be truly or slanderously said, surmised, or thought against the claimant in this suit for an apotheosis among the saints. Thus it is easy to see that the calendar is kept pure, though persons of a cavilling disposition might allege against the equity of this judicial arrangement that, in order to ensure a poetic justice, the devil should be invested with the sole appointment of his deputy, and that it should not be lodged with the court, as is actually the case, without at least his advice and consent. Still, so far as we have read in the "apostolic constitutions," about whose genuineness so much ink has been shed, they contain no proviso of this kind, though it is patent that without it the "inalienable rights" of the aged Nicholas are no more protected than those of South Carolina without such an amendment to the American constitution as shall empower her, in her single sovereignty, to elect a President as well as the other thirty States!It is not, however, its political significance that has beguiled us into a reminiscence of this bit of ecclesiastical history; on the contrary, we have recurred to it because the fancy suddenly struck us that there was some analogy between the amiable task of the Devil's Advocate and that sometimes assumed by the critical functionaries of the press; for, as it is the office of the former to pick a deceased saint to pieces in order to preclude his admittance among the elect of the calendar, so also it sometimes becomes the duty of the latter to pluck a hapless wight of an author until he becomes like Diogenes's edition of Plato's man. And if the newspaper critics are not always given to diabolical detraction of the "presentation copies" which authors and publishers so kindly furnish them, let it not be thought that our analogy fails, for it is hinted that the Devil's Advocate himself, for reasons of his own, has occasionally allowed a candidate for the saintship to pass muster without a very rigid scrutiny. Now, among the reasons which partly tend to induce this suavity of commendatory and stereotyped criticism, we believe there are two worthy of especial mention. In the first place, the critic's "presentation copy" is always fresh from the press, and as he opens it, with paper-cutter in hand, he finds each particular page still redolent of the paper-mill. The perfume of new books is the critic's peculiar incense, and unless the reader, like that most gentle of men and genial of essayists, Elia, is fond of titillating his olfactory by inhaling the extract of printer's ink; unless, like Charles Lamb, we say, he considers a new book superior to any thing of Lubin's, he cannot duly appreciate the kindly and propitiatory influence it experts upon a bland and benevolent critic. And, in the second place, who but the veriest curmudgeon could find it in his heart to indite any thing severe against objects so goodly to the sight as new-bound books, printed, every one of them, in "the highest style of modern art," and profusely embellished with pictures to match? For ourselves, we can never be induced to say aught against those "illustrated editions," all bound in "cloth, full gilt," or "Turkey morocco, extra." Such books are only intended for the centre table or étagère; and if they are only pleasant to the eyes, it matters little whether or not they are like the apple of Eve, to be desired to make one wise. And occasionally, when dulness entombs itself in the garnished sepulchre of Turkey morocco, we call to mind the provident maxim, nil de mortuis nisi bonum.Thus it has come to pass, we imagine, that the bibliographical censors of the press are not always strict to mark the sins against Quintilian and Blair which may be detected in the "complimentary copies" laid on the editorial table. The familiar saw relative to the oral examination of a gift horse would protest against any such procedure. Still, it is undeniable that these self-appointed custodians of the world's literature, especially such as preside over the "reviews" and solemn "quarterlies," attend to this matter better; that is, more in the legitimate spirit of a devil's advocate. However much "bated breath" there may be among the changling critics of the daily press, it is always expected that these oracular organs will deliver the most authoritative and impartial responses; their strictures must be terrible, for, as the motto of the greatest of them all asserts, "Judex damnatur cum nocens absolvitur." The same Publius Syrus who furnished the Edinburgh reviewers this haughty motto of theirs, (though the "smug" Sydney Smith tells us that none of its founders had ever read a line in his dull works;) this same Publius, we say, has another sentiment that must have been written for the especial accommodation of the newspaper critics: "Ad pœnitendum proprat qui cito judicat." Yet the great oracles have not always proved true in their critical vaticinations. To drop our persiflage, it may be doubted whether criticism exerts any thing more than a negative influence on the literature of the day. The most that even a sagacious critic can do is to anticipate the favorable or unfavorable decision that awaits some aspirant for transient or enduring literary distinction, provided such a rare work as that which aspires now-a-days to the latter should come within his ken. For, after all, it is the general sense and sovereign judgment of mankind that must put its broad arrow upon all that is noble in literature, while such works as are destined to a nine days' immortality will find their way to the grocery-stores and trunk-makers fast enough without being shown the road. After some luckless member of the literary Sisyphus family has been laboriously trundling his stone up to the summit, for a surly critic to help it to an additional kick downhill is at once most uncalled for and gratuitously malignant. We hope that our readers will not accuse us of unduly magnifying our office when we assure them that in our estimation the critics are at best only a set of literary jackals, appointed to prey upon authordom and cater for that great lion, the universal public.And how often, besides, has criticism overshot its mark? How many are the opinions of that megatherium of English literature, "the immortal" Doctor Johnson, which the subsequent sense of enlightened men has reversed? Who now-a-days would carp at Milton as he did; who would call Gray a "barren rascal," or vote Fairfax's translation of Tasso a bore, or deny to Tristram Shandy the merit of humor? Or, in later times, was not Lord Jeffrey compelled to unsay much that he wrote while editor of the Edinburgh Review? Has Wordsworth any fewer admirers because the Edinburgh Reviewer met the "Excursion," on its first appearance, with the cheerful exordium of "this will never do!" Is poor Keats less read because the London Quarterly killed him? We trow not. There were many able critics in France during the times of Voltaire, and no one, we presume, has forgotten how the Patriarch of Ferney and his allies in philosophical criticism disparaged a little book over which every reader has wept and melted, the "Paul and Virginia" of Bernardin de Saint Pierre. From these most easily-remembered examples we draw this useful inference, that all the special pleading of a literary devil's advocate cannot prevent a writer of genius from assuming his appropriate place among the auctores classici of his nation and tongue.

The professional criticism of the present day has run into channels somewhat remote from that which was once considered its legitimate province. It concerns itself not only with the application of critical rules to the judgment of literary productions, in which alone criticism may be said technically to consist, but has gradually developed itself into essay writing, so that our critical reviews, quarterlies, and similar periodical literature have become serial publications of essays on all literary and scientific subjects, the name and work of some author being taken as a mere caption to the articles, and having no more to do with the subsequent matter than the texts of certain clergymen have with their sermons: thus, instead of a critical analysis of Mr. Tennyson’s “Princess,” we have an elaborate disquisition on poetry in its nature and essence; instead of a critical examination of Mr. Macaulay’s History of England, we are treated to recondite disquisitions on the Philosophy of History, until the periodical review has become a pamphlet of essays or a fragment of the encyclopædia. If we were disposed on the present occasion to follow the example thus set us by our betters, we should forthwith proceed, taking “Moby Dick, or the Whale,” as our text, to indite a discourse on cetology. Such, however, is not our intention., Nor do we propose, like a veritable devil’s advocate, to haul Mr. Herman Melville over the coals for any offences committed against the code of Aristotle and Aristarchus: we have nothing to allege against his admission among the few writers of the present day who give evidence of some originality; but, while disposed to concede to Mr. Melville a palm of high praise for his literary excellencies, we must enter our decided protest against the querulous and cavilling innuendoes which he so much loves to discharge, like barbed and poisoned arrows, against objects that should be shielded from his irreverent wit. On this point we hope it is unnecessary to enlarge in terms of reprehension, further than to say that there are many passages in his last work, as indeed in most that Mr. Melville has written, which “dying he would wish to blot.” Neither good taste nor good morals can approve the “forecastle scene,” with its maudlin and ribald orgies, as contained in the 40th chapter of “Moby Dick.” It has all that is disgusting in Goethe’s “Witches’ Kitchen,” without its genius.

Very few readers of the lighter literature of the day have forgotten, we presume, the impression produced upon their minds of Mr. Melville’s earlier publications—Typee and Omoo. They opened to all the circulating library readers an entirely new world. His “Peep at Polynesian Life,” during a four months’ residence in a valley of the Marquesas, as unfolded in Typee, with his rovings in the “Little Jule” and his rambles through Tahiti, as detailed in Omoo, abound with incidents of stirring adventure and “moving accidents by flood and field,” replete with all the charms of novelty and dramatic vividness. He first introduced us to cannibal banquets, feasts of raw fish and poee-poee; he first made us acquainted with the sunny glades and tropical fruits of the Typee valley, with its golden lizards among the spear-grass and many colored birds among the trees; with its groves of cocoa-nut, its tattooed savages, and temples of light bamboo. Borne along by the current of his limpid style, we sweep past bluff and grove, wooded glen and valley, and dark ravines lighted up far within by wild waterfalls, while here and there in the distance are seen the white huts of the natives, nestling like birdsnests in clefts gushing with verdure, while off the coral reefs of each sea-girt island the carved canoes of tattooed chieftains dance on the blue waters. Who has forgotten the maiden Fayaway and the faithful Kory-Kory, or the generous Marheyo, or the Doctor Long Ghost, that figure in his narratives? So new and interesting were his sketches of life in the South Sea islands that few were able to persuade themselves that his story of adventure was not authentic. We have not time at present to renew the inquiry into their authenticity, though we incline to suspect they were about as true as the sketches of adventures detailed by De Foe in his Robinson Crusoe. The points of resemblance between the inimitable novel of De Foe and the production of Mr. Melville are neither few nor difficult to be traced. In the conduct of his narrative the former displays more of naturalness and vraisemblance; the latter more of fancy and invention; and while we rather suspect that Robinson’s man Friday will always remain more of a favorite than Kory-Kory among all readers “in their teens,” persons of maturer judgment and more cultivated taste will prefer the mingled bonhommie, quiet humor, and unstrained pathos which underlie and pervade the graphic narratives of Mr. Melville. Still we are far from considering Mr. Melville a greater artist than Daniel De Foe in the general design of his romantic pictures; for is it not a greater proof of skill in the use of language to be able so to paint the scenes in a narration as to make us forget the narrator in the interests of his subjects? In this, as we think, consists the charm of Robinson Crusoe—a book which every boy reads and no man forgets; the perfect naturalness of the narrative, and the transparent diction in which it is told, have never been equalled by any subsequent writer, nor is it likely that they will be in an age fond of point and pungency.

Mr. Melville is not without a rival in this species of romance-writing, founded on personal adventure in foreign and unknown lands. Dr. Mayo, the author of “Kaloolah” and other works, has opened to us a phantamagorical view of life in Northern Africa similar to the “peep” which Mr. Melville has given us of the South Sea Islands through his kaleidoscope. Each author has familiarized himself with the localities in which his dramatic exhibition of men and things is enacted, and each have doubtless claimed for themselves a goodly share of that invention which produced the Travels of Gulliver and the unheard-of adventures and exploits of the Baron Munchausen. Framazugda, as painted by Dr. Mayo, is the Eutopia of Negrodom, just as the Typee valley has been called the Eutopia of the Pacific Islands, and Kaloolah is the “counterfeit presentment” of Fayaway.

Moby-Dick, or the Whale, is the narrative of a whaling voyage; and, while we must beg permission to doubt its authenticity in all respects, we are free to confess that it presents a most striking and truthful portraiture of the whale and his perilous capture. We do not imagine that Mr. Melville claims for this his latest production the same historical credence which he asserted was due to “Typee” and “Omoo;” and we do not know how we can better express our conception of his general drift and style in the work under consideration than by entitling it a prose Epic on Whaling. In whatever light it may be viewed, no one can deny it to be the production of a man of genius. The descriptive powers of Mr. Melville are unrivalled, whether the scenes he paints reveal “old ocean into tempest toss’d,” or are laid among the bright hillsides of some Pacific island, so warm and undulating that the printed page on which they are so graphically depicted seems almost to palpitate beneath the sun. Language in the hands of this master becomes like a magician’s wand, evoking at will “thick-coming fancies,” and peopling the “chambers of imagery” with hideous shapes of terror or winning forms of beauty and loveliness. Mr. Melville has a strange power to reach the sinuosities of a thought, if we may so express ourselves; he touches with his lead and line depths of pathos that few can fathom, and by a single word can set a whole chime of sweet or wild emotions into a pealing concert. His delineation of character is actually Shakspearean—a quality which is even more prominently evinced in “Moby Dick” than in any of his antecedent efforts. Mr. Melville especially delights to limn the full-length portrait of a savage, and if he is a cannibal it is all the better; he seems fully convinced that the highest type of man is to be found in the forests or among the anthropophagi of the Fejee Islands. Brighter geniuses than even his have disported on this same fancy; for such was the youthful dream of Burke, and such was the crazy vision of Jean Jacques Rosseau.

The humor of Mr. Melville is of that subdued yet unquenchable nature which spreads such a charm over the pages of Sterne. As illustrative of this quality in his style, we must refer our readers to the irresistibly comic passages scattered.at irregular intervals through “Moby Dick;” and occasionally we find in this singular production the traces of that “wild imagining” which throws such a weird-like charm about the Ancient Mariner of Coleridge; and many of the scenes and objects in “Moby Dick” were suggested, we doubt not, by this ghastly rhyme. The argument of what we choose to consider as a sort of prose epic on whales, whalers, and whaling may be briefly stated as follows:

Ishmael, the pseudonymous appellative assumed by Mr. Melville in his present publication, becoming disgusted with the “tame and docile earth,” resolves to get to sea in all possible haste, and for this purpose welcomes the whaling voyage as being best adapted to open to his gaze the floodgates of the oceanic wonder world; the wild conceits that swayed him were two—floating pictures in his soul of whales gliding through the waters in endless processions, and “midst them all one grand hooded phantom, like a snow hill in the air.” This “grand hooded phantom,” thus preternaturally impressed on his mental retina, proves to be Moby Dick, a great white whale, who had long been the terror of his “whaling grounds,” noted for his invincible ferocity and for a peculiar snow-white wrinkled forehead, and a high pyramidical white hump on his back. It is not, however, his prodigious magnitude, nor his strange white hue, nor his deformed visage that so much invested the monster with unnatural terror, as the unexampled and intelligent malignity which he had repeatedly evinced when attacked by different whalers, so that no turbaned Turk, no hired Venetian or Malay, could smite his foes with more seeming malice. Ishmael embarks on board the whaling vessel “Pequod,” whose captain, Ahab, had been previously bereft of a leg in an encounter with the terrible “Moby Dick;” a spirit of moody vindictiveness enters his soul, and he determines to be avenged upon the fell monster that had, with such intelligent and prepense maliciousness, rendered him a cripple for life; the white whale swam before him as the incarnation of all those wicked agencies which some deep men, according to Mr. Melville, feel eating in them, till they are left living on with half a heart and half a lung; in other words, Capt. Ahab became a monomaniac, with the chase and capture of Moby-Dick for his single idea; so that all his powers were thus concentrated and intensified with a thousand-fold more potency than he could have brought to bear on one reasonable object. The “Pequod” encounters Moby Dick, and in the deadly struggle which ensues the whole crew perish save the fortunate Ishmael. On such a slender thread hangs the whole of this ingenious romance, which for variety of incident and vigor of style can scarcely be exceeded.

Related posts

- James C. Welling, his Notes on New Books

https://melvilliana.blogspot.com/2024/08/james-c-welling-his-notes-on-new-books.html

- William Allen Butler's friendly notice of The House of the Seven Gables

https://melvilliana.blogspot.com/2024/09/william-allen-butlers-friendly-notice.html

- Moby Dick widely praised in 1851-2

https://melvilliana.blogspot.com/2020/02/moby-dick-widely-praised-in-1851-2.html

No comments:

Post a Comment