Over the years, fans of "The Night Before Christmas" have been puzzled or amused by Clement Moore's legendary reluctance to admit that he wrote it. Misguided attribution sleuths take Moore's supposed failure to acknowledge the Christmas poem formally until 1844 (before January 1837, actually, but still a good thirteen years after its first anonymous publication in December 1823) as circumstantial evidence for authorship by Henry Livingston, Jr. Moore's poem has been so spectacularly famous for so long, readers today naturally wonder who wouldn't wish to be immortalized as its author. Only a hopelessly stuffy academic could be embarrassed by association with such universally delightful verses.

Maybe so, but the ridicule that the distinguished seminary professor might have expected, and feared, was remarkably quick in arriving. Soon after Moore revealed his authorship of "A Visit from St. Nicholas" in The New-York Book of Poetry, Laughton Osborn gave "Prof. Moore's nursery rhymes" thumbs down in The Vision of Rubeta (Boston, 1838), a brilliant if demented exercise in verse and prose that one contemporary review judged "remarkable for its wholesale satire and unlimited abuse of every thing and every body" (Washington, D. C. Madisonian, November 25, 1841). Moore was in pretty good company, since the chief objects of Osborn's satire were newspaper editors William Leete Stone Sr of the New York Commercial Advertiser and Charles King of the New York American.

Stone and King had published stinging criticism of Osborn's earlier effort, Sixty Years of the Life of Jeremy Levis. Negative reviews evidently motivated Osborn's relentless satire of the prominent New York editors and their respective newspapers in the text and extensive footnotes of Rubeta. Stone appears thinly disguised as "Rubeta," King as "Petronius."

|

| New York American for the Country - December 31, 1836 |

To make sure readers get the point of the satire in verse, Osborn in prose glosses the apostrophe to the "loveliest book that ever cumber'd stall / Where all Manhattan's costive infants squall" as a reference to The New-York Book of Poetry (figured in the verse as equally fit for book-stall and bathroom-stall). In the footnotes ("libelous notes," according to his 1878 obit in the New York Express), Osborn launches a sustained attack on Moore's best-known contribution, as King had quoted it in the New York American:

"We regret to see this nonsense from so very respectable a man.... Such trash is not to be given to the public as pretty poetry, though it were the product of the whole faculty."

Below, the entire screed from The Vision of Rubeta:

... The other selection is "A Visit from St. Nicholas. — By C. C. Moore." (— puerique patresque severi carmina dictant. [quoting from Epistles of Horace, 2.1]) En voici le style:

"A bundle of toys he had flung on his back,

And he look'd like a pedlar just opening his pack." etc etc.

"The stump of a pipe he held tight in his teeth,

And the smoke it encircled his head like a wreath.

He had a broad face and a little round belly,

That shook, when he laugh'd, like a bowl full of jelly." etc etc.Vos o patricius sanguis, quos vivere fas estWe regret to see this nonsense from so very respectable a man: but

Occipiti coeco, posticae occurrite sannae. [quoting the Satires of Persius, 1.61-2]

When grave professors stoop to follywe have nothing left us but to do our duty. Such trash is not to be given to the public as pretty poetry, though it were the product of the whole faculty §:

And find too late the Muse betray,

Parodying famous lines by Goldsmith from Stanzas on Woman, Osborn turns Goldsmith's "lovely woman" into "grave professors," and deceitful "men" into a treacherous "Muse." The attack on Clement C. Moore in The Vision of Rubeta is also interspersed with quotations from Osborn's classical models for satire, here Horace and Persius. Osborn identifies all three sources in footnotes to the footnotes. With his quotation from the Epistles of Horace Osborn ridicules the homely theme and content of Moore's verses for children:Hos pueris monitus patres infundere lippos

Cum videas, quaerisne unde haec sartago loquendi

Venerit in linguas? [again quoting from Satires of Persius, 1.79-81]

... sons and their stern fathers,Moore's rhyme of "belly" with "jelly" triggers the first of two quotations from Persius. For emphasis apparently, Osborn italicizes the Roman satirist's picture of a patrician geezer cursed with "a blind occiput" (lacking eyes in the back of his head). In other words:

Hair bound up with leaves, dine, and declaim their verse. --Poetry in Translation

"You blue bloods, who have to live backwards-blind, turn around and face the gibing behind you." --as translated by Daniel M. Hooley in The Knotted ThongWith his second quotation from the Satires of Persius, Osborn effectively likens Moore both as teacher and poet to leaky old men who lecture in a jambalaya of popular jargon, sartago denoting literally a frying pan.

When these are the lessons which you see purblind papas pouring into their children’s ears, can you ask how men come to get this hubblebubble of language into their mouths? --Satires of A. Persius Flaccus, translated by John ConingtonBut Persius does not quite finish off Moore in The Vision of Rubeta. Having slammed one flattering review of The New-York Book of Poetry in the New York American, Osborn goes on to criticize another in the New York Review:

Having done this act of justice, let us ask, how it happens that the N. York Review, (No. ii.,) in noticing the Book of Poetry, selects for commendation the nursery rhymes of Prof. Moore, and the romantic stuff of Mr. Hoffman, while it passes entirely the verses of Mr. Seymour, and the other few pieces which show something like good sense, strong thought, and felicitous expression? Was it that Mr. H. is the editor of a Magazine, and Prof. Moore an influential member of society, and of connexions influential in society, and that both were possibly personal friends of the Reviewers? A want of independence, in a Review which professes to be impartial, is a want of honesty. --The Vision of RubetaOsborn's rhetorical question implies the answer, "Yes." His charge of favoritism is undoubtedly true: the impolite observation of an outsider looking in.

Melville readers and students may be more interested in The Montanini; The School for Critics (New York, 1868) where Osborn blasts Herman Melville's friend Evert A. Duyckinck among others.

For their part, the Duyckinck brothers did not fail to give Laughton Osborn space in the Cyclopaedia of American Literature. Another biographical entry for Laughton Osborn may be found in Appleton's Cyclopaedia of American Literature.

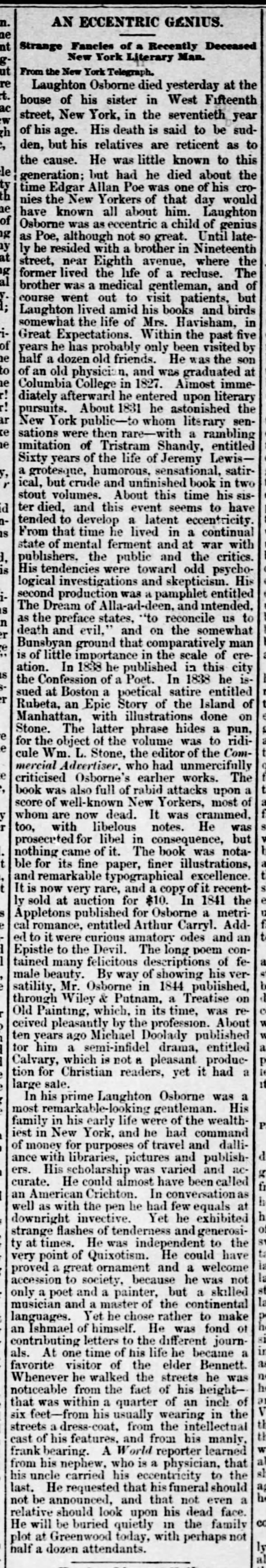

Obituary notices described Osborn as "an eccentric genius" and compared his lonely lifestyle to that of Miss Havisham in Great Expectations.

· Thu, Dec 26, 1878 – Page 4 · The Saline County Journal (Salina, Kansas) · Newspapers.com

· Thu, Dec 26, 1878 – Page 4 · The Saline County Journal (Salina, Kansas) · Newspapers.com

No comments:

Post a Comment