Young "Ben Fox" is said to be alone, "SOLUS," the only person left in the editorial office of the Daily Delta, yet the strong criticism of Pierre first arrives in another voice, disembodied.

"Ben Fox SOLUS. In the absence of the other young gentlemen, who have gone "across the Lake," and left him alone with the items, he is compelled to soliloquize."Being alone, Ben Fox is "compelled to soliloquize." In context then, the voice of Melville's critic is best understood as that of the solitary editor in dialogue with himself. Further along in the review, commenting on the style and peculiar diction of Pierre, Ben Fox asserts himself in the first person: "I, Ben Fox ...." Still, accepting the conceit as presented, the critic of Pierre may be regarded as essentially a figment of the narrator's imagination and therefore--a ghost.

Considering the strong distaste expressed for the novel's "disgustingly immoral" contents, the depth of the engagement with them also seems remarkable. Ghost or no, Melville's New Orleans critic read to the end.

Who was he? As confirmed in The Young Irelanders by Thomas F. O'Sullivan, Benjamin or Ben Fox was a pseudonym of Joseph Brenan (1828-1857), the exiled Irish patriot, poet, and journalist who served for several years as literary editor of the New Orleans Daily Delta. (Aka Joseph Brennan.)

On his release without trial in March, 1849, Brenan became editor of the Irishman, which had been started in Dublin by Bernard Fulham, and for six months strove to rekindle the insurrectionary flame in the country. He was implicated in the attack on the Cappoquin police barracks on the 16th September, and in October escaped to America, where he became connected with a number of journals, including Horace Greeley's Tribune, Devin Reilly's People, the Enquirer of Newark, [New] Jersey, and the New Orleans Delta (in which he wrote a series of papers under the pen-name "Ben Fox").One New Orleans friend described Brenan as a "fire-eater," a brilliant writer and fanatic Southerner, but unfortunately

--T. F. O'Sullivan, The Young Irelanders (Tralee: The Kerryman, 1944), pp. 354-5.

"reckless and desperate in his conduct, as if driven by the Furies." --Donahoe's MagazineIn 1853 (less than one year after publishing the extended attack on Pierre) Brenan contracted yellow fever. Back in New York City for a brief spell in 1854, he collaborated with John Mitchel on the anti-English and pro-slavery New York Citizen. He suffered blindness and wrote about it, in a poem that Melville's friend Evert A. Duyckinck reprinted in The Literary World on November 12, 1853. Brenan died in 1857, in his 29th year.

Earlier in 1852, before publication in August of the two "Nights in Our Office" sketches, Brenan contributed essays under various headings including "Literary Half-Hours," "Fresh Gleanings" (a title confessedly plagiarized from Donald Grant Mitchell aka Ik Marvel), and "Marginalia" (another borrowed title, from Poe, giving "extracts from the notebooks of Benjamin Fox"). Perhaps foreshadowing Brenan's dim view of Pierre, Brenan discounted the sudden popularity of Typee by claiming in one of his "Fresh Gleanings" columns that Herman Melville

"was made a favorite by one review in Blackwood."

--New Orleans Daily Delta, April 11, 1852

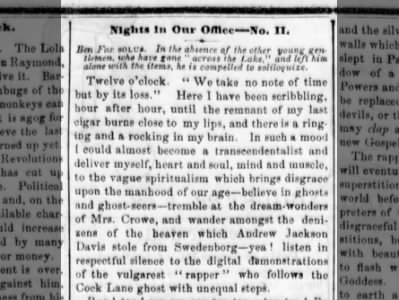

The first installment of "Nights in Our Office" appeared in the Sunday morning supplement to the New Orleans Daily Delta on August 15, 1852. No. I reported the after-midnight conversation among three persons in the the editorial office: "Esculapius," "Benjamin Fox," and "The Gaul." Their late night talk touches on literature, politics, and New Orleans society.

As noted above, No. II (August 22, 1852) unfolds as the soliloquy of Ben Fox, writing copy and talking to himself. The tapping sounds made by working typesetters or compositors punctuate the night editor's thoughts and writing.

The nocturnal tapping in several places evokes the practice of spirit-rapping.

"Rap! tap! rap-rap-rap-tap-tap-a-tap-tap! By the memory of all infernal noises, there are the spirits!"Melville would similarly associate eerie tapping ("Tick! Tick!") with belief in spirits and spirit-rapping in his short fiction, The Apple-Tree Table (subtitle: "Or, Original Spiritual Manifestations"). "Ben Fox" almost anticipates Melville there, when he guesses that

"It might be some insect which has got inside the wainscotting."Other familiar noises of the night, besides "the click-clack of the type," are the proofreader's "monotonous voice" and "the hissing sound of the steam-engine."

But the click-clack of the type is regular as ever. The monotonous voice of the proof-reader is unbroken in its flow, save when there is a pause to cross a t, or put a dot over an i, and the hissing sound of the steam-engine, which is impatient to stretch forth its strong arm and work, continues its drowsy sameness.Occasionally the Printer's Devil emerges, too, and sneaks a mischievous comment into the editor's copy.

After a good deal of fretting, Ben Fox manages to convince himself the rapping sounds he hears in the editor's office are not made by ghosts. How long his conviction will hold out, remains uncertain.

Found on Newspapers.com

From the New Orleans Daily Delta, August 22, 1852:

Friend Ben, it must not be. We must discountenance such absurdity. We must laugh down this rapping infamy, and crush it. We must put our paws on the supporters of it: and, if we cannot do so by gentle means, we must e'en follow your example, and--try them with the Latin! [by speaking a Latin formula for exorcism, like Dominie Sampson in Scott's Guy Mannering]. The practical results of the rascally nonsense are becoming too apparent every day. We have spiritual societies in progress of formation, newspapers edited by spirits, with the aid of gin-and-water, and suicides justified by messages from the supernal finger-points. We have a literature of the skies growing up, and distinguished authors assuring the world that they cannot write save when in nubibus. (A delicate way of saying "high," doubtless.--PRINTER'S DEVIL.)

Dear Ben: On the table, near you, is lying a specimen of the transcendental balderdash which is sent forth in good type and binding by the professors of the new religion. Let us glance at it. First, however, I will give you a brief outline of the story.

It is called "Pierre on the Ambiguities"--an ambiguous denomination enough--and has the name of Herman Melville, as the author, on the title page. It is a tale of spiritual wonders. Pierre, the son of a proud and haughty widow, is a young gentleman of literary tastes, who is on terms of singular familiarity with his mother. He calls her sister, and she always treats him as her brother. At the age of nineteen, Pierre, of course, is in love, and with a young girl whose name is Lucy, remarkable for nothing but never talking in any style save that which you and I are accustomed to call "highfalutin." The first portion of the book is taken up with their conversations, which leave those of Romeo and Juliet far behind them. As you read them, the conviction is forced upon you that those three individuals are as mad as the author, but you could not yet suppose that they are as bad. The second part contains the story of Isabel. This young lady meets Pierre one day, and shrieks. Ever after, her face haunts him. He neglects Lucy, and insults his mother. He suddenly becomes blasphemous, and inhospitably fires paradoxes at the head of a respectable clergyman who visits the family. He addresses the moon and stars, and makes speeches which would take the wind from Governor Foote [Henry Stuart Foote] or old Bullion [Thomas Hart Benton]. The beauty of his monologues is their profound incomprehensibility. They are unintelligible enough to have been dreamed by Swedenborg, or "communicated" to Andrew Jackson Davis.

One day Pierre receives a letter. It is signed by Isabel, and calls him her brother, praying him at the same time in very feminine, though rather dangerous terms, to come to her, and take her to his heart. Without any hesitation he goes and embraces her in a warmer manner than what we usually designate fraternal, before she communicates the proof of their relationship. Then Miss Isabel commences a long and misty narrative, which hints at the fact or the falsehood--for the author does not say which--of her being the illegitimate daughter of Pierre's father. She has no reason for thinking so. The transcendental young gentleman has no cause to believe it, but his resolution is taken on the spot. He is determined to save his parent's character--which the public had never assailed, and as far as we could surmise, would never trouble itself withal, provided Isabel held her tongue--and to carry out his object proceeds to ruin his own happiness. Isabel, he says, must live with him. Must consent to be called his wife, and share his fortunes for better or worse. They accordingly run away to New York, where Pierre enters a Fourierite society, and becomes an author. Their mode of living is somewhat equivocal, though mention is made of two rooms. Their residence is in the "House of the Apostles," w[h]ere a number of rappers have congregated for the express purpose, doubtless, of humbugging the world and themselves. Meantime, Pierre's mother dies of a broken heart, and Lucy--the old flame--is despaired of. By the deceased mother's will, the young transcendentalist is disinherited, and compelled to seek bread with his pen, which does not prove very profitable.

So far so good. But unfortunately, Lucy recovers and flees from her family in search of her lover. She arrives at the Apostles and is obliged to take share of Isabel's bed. Then there is the devil to pay. It is impossible to decide which is Mrs. Pierre. They cannot themselves determine which is which. Spiritualism is no use in this fix, for both go in for women's rights. Meanwhile the gentleman writes books and receives insulting messages from the publishers. Lucy paints portraits, and Isabel, jealous of her earnings, announces that she will teach the guitar. We regret to say she did not understand the instrument, however, and had to give up her project. The family quarrel increases. 'Pierre or death' is the cry of both the women--neither will give him up, and there would have been a very pretty row did not the brothers of Lucy arrive and strive to take her back to her home. Their efforts were in vain, for she held on to the bannisters like a heroine, while Pierre shot one of the brothers. Isabel, Lucy and Pierre were consequently taken to the Toombs, where they anticipated the usual legal forms with the vulgar termination, and killed themselves by swallowing poison!

Such is the tale. It smacks more of romance than reality. The details are unpleasant, and the theories put forward in the course of the narrative disgustingly immoral. The style is a hybrid--an ugly cross between Carlyle and Swedenborg. It has something of Willis about it, too. The sentences are dressed like unmeaning fops, and sometimes display a species of pinchback respectability. Occasionally they are so devoid of any scintilla of sense, that they become quite laughable.

We give a specimen or two for the benefit of persons who may not be acquainted with the manner of writing, which has resulted from spiritual rapping, and such like things. Describing Pierre's boyhood, the author says: "In the country then Nature planted our Pierre; because Nature intended a rare and original development in Pierre. Never mind if thereby she proved ambiguous to him in the end, nevertheless in the beginning she did bravely. She blew her wind-clarion from the blue hills and Pierre neighed out lyrical thoughts, as at the trumpet blast a war-horse pawed himself into a lyric of foam." I, Ben Fox, must remark, en passant, that I have heard many persons called "old hoss" before this, but "young hoss" is an epithet not at all familiar to me. If, moreover, any person skilled in rappings, can inform me what is meant by a war-horse pawing himself into a lyric of foam, I would feel under a compliment to the expounder. I fear, though, an Edipus cannot be found to read the riddle. But, let the young man proceed: "She, (viz: Nature,) lifted her spangled crest of a thickly-starred night, and forth at that glimpse of their divine captain and Lord, ten thousand mailed thoughts of heroicness (bur-r-r! what a tooth-grinder of a word!) started up in Pierre's soul and glared round for some insulted good cause to defend." Mailed thoughts glaring round! upon my personal honor! they seem uglier than the spirits.

Here is a morsel of love-talk: "Wondrous fair of face, blue-eyed, and golden-haired, the bright blonde Lucy was arrayed in colors harmonious with the Heavens. Light blue be thy perpetual color, Lucy; light blue becomes thee best--such the repeated azure counsel of her aunt Tartan. On both sides, from the hedges, came to Pierre, the clover bloom of Saddle Meadows, and from Lucy's mouth and cheek came the fresh fragrance of her violet young being."

"Smell I flowers or thee?" cried Pierre.

"See I lakes or eyes?" cried Lucy, her own gazing down into his soul as two stars into a tarn."

The allusion to Lucy's being "light-blue" in the foregoing extract may be accounted for by the fact that she, too, was somewhat of a literary character. The "azure counsel," though, puzzles us. We have heard of a verdant advice, but an azure one is something new. The beauty of the queries touching Pierre's nasal and Lucy's visual organs, of course, we need not point out.

Towards the middle of the book a clergyman is introduced, whose personal appearance is hinted at in the following sentence: "As Pierre regarded him, sitting there so meek and mild,--such an image of white-browed, and white-handed and napkined immaculateness,--and as he felt the gentle human radiations which came from the clergyman's manly and rounded beautifulness, he felt that if to any one he could go with Christian propriety and some small hopefulness, the person was the one before him." This description is original, is it not? That "napkined immaculateness" is a touch worthy of the smartest waiter in the City Hotel; and the friends of our fellow-citizen, the well-known official, Abdomen, can appreciate the delicacy of the phrase "rounded beautifulness."

But it is in metaphysical morality our author shines with fullest lustre. We have read many dissertations on the subject of Good and Evil, Virtue and Vice; but the following concise definitions are worth the whole of them. Its chief merit, as our readers must remark, is its simplicity and intelligibility. Pierre and Isabel are in conversation.

"Tell me, what is Virtue? Begin."

"If on that point the Gods are dumb, shall a pigmy speak? Ask the air!"

"Then Virtue is nothing?"

"Not that."

"Then Vice?"

"Look; a nothing is the substance; it casts one shadow one way, and another the other way, and these two shadows cast from one nothing--these, it seems to me, are Virtue and Vice."

As a pendant to the above very clear explanation, we beg leave to suggest that two and two make twenty; but twenty looks towards a hundred, and casts a shadow of a naught, and therefore, a naught is considerably more than ninety-nine!

But enough of this trash. I would not have mentioned the book at all, friend Ben, but as an instance of the rabid nonsense which is the result of the spiritual mania. Away with it--away with it. God's stars shine in their place still, and we will not allow filthy oil-lamps or farthing candles to be substituted for them. God's truth is simple, and it shall not be oppressed under a load of stupid stuff. God's law is eternal, and will out-live all the tricks of imposture, and the blasphemy of bastard philosophies.

Meanwhile--tap! Ha! there it is again. Come back, are you? Well, you are fools for your pains. Tap, tap--very singular, I admit, but gammon still. Very awful at this hour, too, and suggestive of shivering.

Tap! Good night. I must get home. Probably, however, you, thirsty denizen of the noisy land, would join me in a "smile." Tap, tap. Deuce fear you, I knew you would.

(Exit Ben, fumbling in his pockets.)Two of the better-known poems by Joseph Brenan are reprinted in The Popular Poets and Poetry of Ireland.

Herman Melville owned a copy of Poems by James Clarence Mangan (New York, 1859) with Mangan's ballad "To Joseph Brenan" (not marked). You can now see digitized images of the volume Melville owned courtesy of Houghton Library, Harvard University:

http://nrs.harvard.edu/urn-3:FHCL.HOUGH:25047828Below, another copy via the great Internet Archive:

No comments:

Post a Comment