Bad for the heart, bad for the mind,

Bad for the deaf and bad for the blind.

-- Lowell George, Teenage Nervous Breakdown

The most thorough critical study of Herman Melville's 1839 "Fragments from a Writing Desk" is still the one by William Henry Gilman in Melville's Early Life and Redburn (New York University Press, 1951) pages 108-122. While admitting the limitations of Melville's first known fictions as "distinctly amateurish compositions," Gilman argues that the two numbered newspaper "Fragments"

offer clues about his personality, outline his intellectual life, and foreshadow his later literary techniques. --Melville's Early Life, page 109

After close readings of each sketch Gilman concludes, in part:

It is lamentable that no other writings survive from Melville's early period to study for Byronic influences. But Melville's first compositions owe much to Byron, not only in direct and indirect references, but also in the extravagant expression, in the disposition to project one's self or one's dreams into one's literary creations, as Byron did in Childe Harold, and in the sting of disillusion with which the second "Fragment" ends.

In the final analysis Melville's first writings tell us a good deal about their enthusiastic but untutored author. In his twentieth year, despite the dismal days on which he had fallen, he could write with good humor and spontaneity, welling up out of an undeniable urge to self-expression. His attitude toward life is lusty and bumptious. The suggestions of romantic revolt against his refined and thoroughly proper background are strong. If his enthusiasms are somewhat youthful, they still evidence zest for the life of experience as well as for art and literature, both classical and modern. He could indulge in the wildest of romantic effusions, as in the first "Fragment," and much of the second. However, he could also subdue them with humor, ridicule, and disenchantment.

His literary style has the faults common to beginners--verbal and imaginative extravagance, self-consciousness, undue length. Yet in many ways his first works anticipate the style of his best period. He learned very early to fill out his story with a wealth of allusion, literary, historical, and artistic. The Second "Fragment" begins with an exclamation as do Typee and Mardi; its abruptness is repeated in Redburn, White-Jacket, and Moby-Dick. The suspense secured by deliberately delaying the ending and the dramatic climax itself are repeated in Typee and Mardi and worked out in Wagnerian form in Moby-Dick. Of profound significance is the fact that the "Fragment" tells the story of a frustrated quest. The pattern of this adolescent experiment with the marvelous is the essential pattern of Mardi, Moby-Dick, and Pierre. Here Melville's hero pursues the trivial end of sensuous perfection. At the very end he is suddenly disappointed. In the works of Melville's greatest period his characters wander over the entire globe and the infinite world of the mind and in the pursuit of ultimate beauty, or of power over nature and evil, or of truth and justice. All of them--Taji, Ahab, and Pierre--are the losers in their quests. The ending of the second "Fragment" shows that as early as his twentieth year Melville's mind had formulated, however crudely, the concept that pursuit of the ideal is foredoomed to disillusion and defeat.

-- William H.Gilman, Melville's Early Life, pages 119-120.

The best edited texts of Melville's two "Fragments from a Writing Desk" are printed with "Uncollected Pieces" in the scholarly edition of The Piazza Tales: And Other Prose Pieces, 1839-1860, edited by Harrison Hayford, Alma A. MacDougall, G. Thomas Tanselle and others (Northwestern University Press and The Newberry Library, 1987) on pages 191-204. "Fragments" originally appeared in two numbered installments, each published over the enigmatic signature "L. A. V." in the Lansingburgh NY Democratic Press, and Lansingburgh Advertiser for May 4 and 18, 1839. The pseudonymous author was then 19 years old. The joke at the sudden end of Fragment No. 2 is on the narrator who finds out to his horror that his Oriental dream girl is "DUMB AND DEAF!" physically unable to speak or hear. What an idiot! The narrator I mean, so devoted to his ideal of feminine perfection that he runs away from Real Love the instant he finds it.

Even with due allowance for the exuberance and stupidity of youth, the premise of the "atrocious anticlimax" (Gilman's apt tag, page 113) that finishes off Melville's second Fragment is hard to comprehend. His mystery-girl ain't nothing but fine fine fine. How is her being deaf-and-dumb a dealbreaker? Omnia vincit amor, all the poets say so. Muddy Waters said she moves me, man. Jimmy Reed said if you find true love in this wicked world, sign her to a contract. Chuck Berry said C'est la vie, you never can tell. Big Maybelle said why not take all of me. Obviously Melville never saw Marlee Matlin in Children of a Lesser God. Reject that sexy enchantress? Not hardly.

"has been appropriately called the first of his variations on the theme of a frustrated quest. The final anticlimax is the earliest demonstration of his irresistible impulse to prick the rosy bubble of romance and to reveal its terrible core of tragic reality." -- Finkelstein, Melville's Orienda (Yale University Press, 1961; reprinted Octagon Books, 1971) page 31.

Norberg, Peter. "Congreve and Akenside: Two Poetic Allusions in Melville's "Fragments from a Writing Desk"." Leviathan, vol. 10 no. 3, 2008, p. 71-80. Project MUSE muse.jhu.edu/article/492877.

"the deliberate manner in which Melville directs readers’ attention back to the narrator’s overblown rhetoric makes his rhetorical posturing, not women, the butt of the joke."Similarly excused as a literary device, the narrator's heartless rejection of a disabled woman after the big reveal. Call it a metaphor, rather than obvious ableism. The shocking silence of Inamorata figuratively represents

"the romantic movement’s failure to propose an alternative to the cultural order of things it ostensibly challenged" (page 76).

Maybe, but my own research, particularly my deep reading in National Lampoon, teaches me that premium adolescent humor revels in misogyny, along with gross outrageous satire of everything under the sun. Not excluding the most vulnerable of our fellow mortals with disabilities. Also, as a committed feminist I refuse to bar women from any exposé of posturing and butts, however academic or adolescent. No More Separate Spheres! Speaking of which, the contribution by Elizabeth Renker to that seminal volume offers probably the best analysis ever of the literary figurations in Melville's Fragments:

The virgin whiteness thematized in these sketches under the sign of the female is metonymically the whiteness of paper and is ultimately figured as a blankness or dumbness that terrifies the narrator/writer.... (pages 104-105)

In the confrontation with the dumb white face that concludes sketch 2, then, the writing debut of sketch 1 ultimately gives way to a terrifying scene of writing anxiety.” (pages 105-106)

Reprinted there from Renker's 1994 article in American Literature

Renker, Elizabeth. “Herman Melville, Wife Beating, and the Written Page.” American Literature, vol. 66, no. 1, 1994, pp. 123–150. JSTOR, www.jstor.org/stable/2927436.

Couch, Daniel Diez and Michael Anthony Nicholson. "Silent Eloquence: Literary Extracts, the Aesthetics of Disability, and Melville’s “Fragments”." Leviathan, vol. 23 no. 1, 2021, p. 7-23. Project MUSE, doi:10.1353/lvn.2021.0001.

“How, then, to cull from the invectively capitalized last words of Melville’s text some sense of his profound and provoking explorations of disability?

but realizes, as a reader, you don't. Melville's Inamorata is, after all, imaginary. A fictional character, and barely that in Snediker's view:

“Conceiving Inamorata as a woman treated like an object asks, however, that we suspend our readerly disbelief regarding her elaborate textual flatness.” -- Michael D. Snediker, preface to Contingent Figure.

an American model for Melville's story which has not been previously noted. The subject of the deaf and dumb mistress is the theme of Amir Khan, a popular Oriental verse romance by a young American poet, Lucretia Maria Davidson, who died in 1825 at the age of sixteen....

Like the Inamorata of Melville's Fragment, Amreta, the heroine, is deaf and dumb and is characterized by "long dark lashes" and an appropriately amorous name. The passionate ardor of Amir Khan meets no response in the beauteous damsel. But Amir Khan finally resorts to a ruse. With the help of a magic herb, he pretends to be dead and succeeds in evoking speech in his mistress. Unlike Melville's Fragment, the story ends happily.

... Miss Davidson was inspired by the Arabian Nights and even more by Thomas Moore, the Western prophet of Oriental romance. One cannot help feeling that Amir Khan may have given Melville a special impetus for his "hoax."

--Melville's Orienda, pages 29-33

Speak! Tell me, thou cruel! Does thy heart send forth vital fluid like my own? Am I loved,--even wildly, madly, as I love?

"Oh speak! Amreta--but one word!

Let one soft sigh confess I'm heard."

Davidson's models were Melville's, too. As pointed out in a contemporary review, Davidson's poems

“are to be estimated by the age of the writer, and by the subjects of imitation before her—Byron and Moore; from whom all our young poets and poetesses have more or less made their sketches. And why not,—if the sketches be tolerable? " -- New York Spectator, June 2, 1829.

In "Fragment 2," he continues the satire of the idealization of women in popular romantic fiction begun, and put in contrasting perspective, by "Fragment 1." The absurdly saccharine and lace-edged female portraits of "Fragment 1" evolve in "Fragment 2" into a mysterious lady who, much to the narrator-hero's chagrin, turns out to be deaf and dumb....

... The main joke of the piece centers on Poe's preoccupation with mysterious women of ethereal beauty and perfection. In "Fragment 2," the narrator's quest does not lead to a great transcending love that transports him to a vision of Poe's Other-World but to the hard reality (presented as black humor) that the loved one, very much of this earth, is deaf and dumb. The satire may cut deeper to suggest that her dress, surroundings, and general appearance disguise her defects, or even deeper to suggest ironically that if she is a supernatural emissary she can neither hear man's petitions nor speak any wisdom or comfort to him. But the general tone of the "Fragment" is light and humorous, and highly serious thematic interpretations probably should not be pushed too far.

Obuchowski, Peter A. "Melville's first short story: a parody of Poe." Studies in American Fiction, vol. 21, no. 1, 1993, p. 97+. Gale Academic OneFile, link.gale.com/apps/doc/A13926333/AONE?u=nypl&sid=AONE&xid=9008082d.

For Obuchowski, Melville's 1839 parody of Poe revealed a talent for literary satire that would be developed and exploited throughout Melville's career as a prose writer, most brilliantly in The Confidence-Man.

Otter, Samuel. "Introduction: Melville and Disability." Leviathan, vol. 8 no. 1, 2006, p. 7-16. Project MUSE muse.jhu.edu/article/492743.

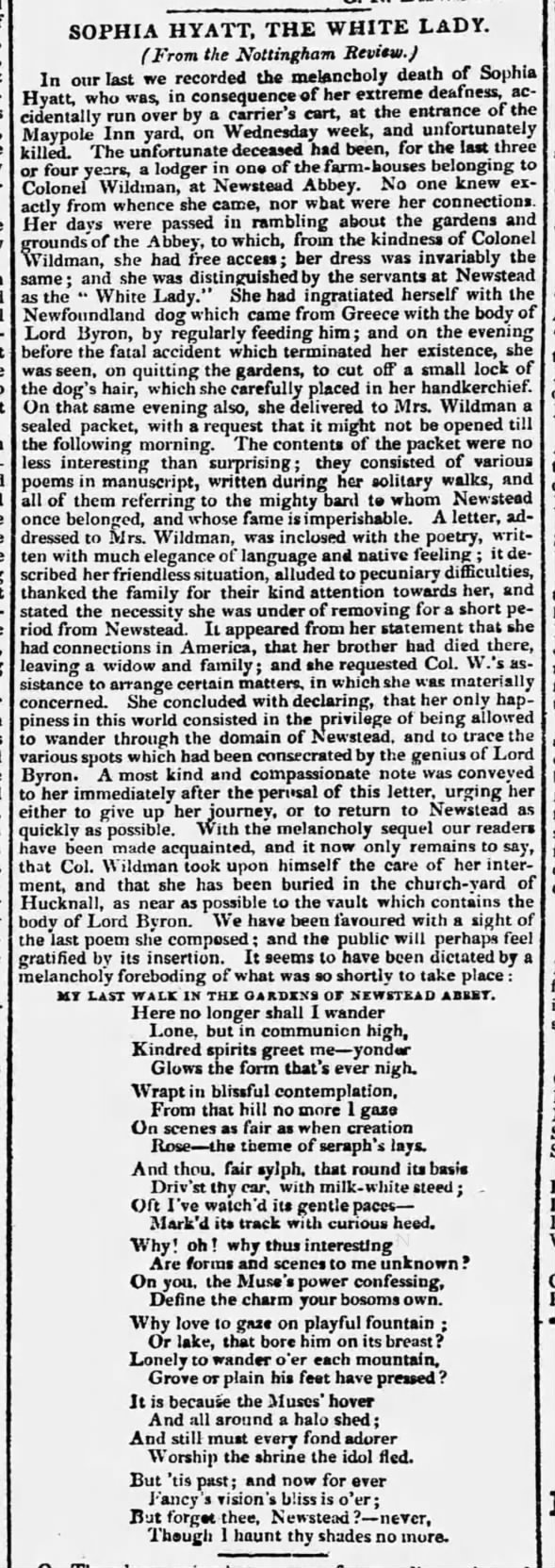

The White Lady of Newstead

http://www.nottshistory.org.uk/hucknall1909/hucknall14.htm

12 Oct 1825, Wed The Bury and Norwich Post (Bury, Suffolk, England) Newspapers.com

12 Oct 1825, Wed The Bury and Norwich Post (Bury, Suffolk, England) Newspapers.com

Reprinted frequently, for example in the London Mirror of Literature, Amusement, and Instruction (October 8, 1825). American versions include the New York Spectator for December 2, 1825; New York Truth Teller, December 3, 1825; and Springfield, MA Republican, December 7, 1825.

|

| New York Truth Teller - December 3, 1825 |

"Melville's active, signing women serve as a rejoinder to Hale and Irving, whose objectifying fictions combine ableism and antifeminism." -- Couch and Nicholson on Melville and Disability, page 17.

Hahaha.

Objectifying fictions? Personally, I live for objectifying fictions.

Peeping from beneath the envious skirts of her mantle, and almost buried in the downy quishion on which it reposed, lay revealed the prettiest little foot you can imagine; cased in a satin slipper, which clung to the fairy-like member by means of a diamond clasp.

Talk about active signing. Baby, you know what I like. Do that sign with the downy quishion.

Mary had a little lamb,

Its fleece was white as snow. -- Sarah J. Hale and Buddy Guy

Mary had a little lamb,

His fleece was black as coal.... -- Stevie Ray Vaughan

Melville's active, signing women serve as a rejoinder to Hale and Irving, whose objectifying fictions combine ableism and antifeminism: as Hale writes, "a beauty who cannot speak, is no more . . . than a statue" (226).

Great God! As presented in Leviathan, the severed quote makes Hale sound like the ultimate ice-queen, mean and evil enough to categorically deny human dignity to non-speaking persons. Case closed. Anybody who would cruelly marginalize disabled people by calling them statues could probably dash off five or six ableist fictions before breakfast. But that only happens in pseudo-reality. In the real world of verifiable facts, here's what Hale actually wrote:

But a beauty who cannot speak, is no more to our intellectual beaux than a statue. And yet, where is the great advantage in having the faculty of speech, if it be only employed in lisping nonsense?

"She was as happy as she seemed, as happy as she was innocent—she had never known a single sorrow, or privation." (Deaf Girl, page 227)

Sophia Hyatt

Roberson, Jessica. "Remembrance and Remediation: Mediating Disability and Literary Tourism in the Romantic Archive." Studies in Romanticism, vol. 59, no. 1, 2020, p. 85+. Gale Academic OneFile, link.gale.com/apps/doc/A625498000/AONE?u=nypl&sid=AONE&xid=9fe2e60c. Accessed 11 May 2021.

2 + 2 = 4-fold exegesis for hardcore medievalists

1. Literal.

2. Allegorical.

3. Moral.

4. Anagogical - Spiritual.

Mr. EDITOR, – The notice of the deceased Sophia Hyatt, “the White Lady,” which appeared in your Paper a few days since, having met my eye, I beg to inclose you a little piece from the pen of that unfortunate, but interesting female. It is now, perhaps, about 30 years since I met with her at the house of a lady in Hoxton. Miss Hyatt was a native of Ireland: she had received a liberal education, and was possessed of a small annuity. Her deafness and other bodily afflictions were occasioned by fits; and those afflictions, with the eccentric & romantic turn of mind that she possessed, rendered her an object of great interest to those to whom she happened to be known. Among such she distributed her poetical effusions: the sonnet to “Insensibility” is that with which she favoured me. From the kind attention paid to the unfortunate subject of this letter by the family of Colonel Wildman, I have some hope that the Poems committed to them by the deceased, will be suffered to meet the public eye.— And am, Sir, your humble servant,

E. B.

Walworth, October 6.

TO INSENSIBILITY.

Thou foe profess’d to joy, grief, hope, despair,

With all the ills that from those sources flow,

Insensibility! Oh hear my pray’r,

And give a bless’d oblivion to my woe.What though, confess’d, joy brightens not thy mien,

Nor pleasure sparkles in thy vacant eye,

No pang can reach that bosom’s calm serene,

Arm’d with thy shield, Insensibility!What though the foe of ev’ry Muse divine;

Nor where thou art can Fancy’s radiance beam;

What is the Muses—Fancy’s bliss to thine?

Thine—undisturb'd repose—theirs, a perturbed dream!

Come, then, thou truest, only friend to peace,

Possess my soul, and bid its sorrows cease.

-- London Morning Chronicle, October 6, 1825; reprinted in the Baltimore, MD Gazette and Daily Advertiser, January 5, 1826.

No comments:

Post a Comment