Signed "Deuceace" and published under the major heading "Authors in the Shade" in the St. Louis Globe-Democrat (November 19, 1876):

AUTHORS IN THE SHADE.

The Fleeting Character of Literary Reputation--Noted Names Obscured by Twenty or Thirty Years.

Puffer Hopkins Brought to the Surface--The Dickens of America in a Saturnine Business.

The Widow of Maj. Jack Downing as a Septuagenarian--

A Gifted Tailor [Sailor?] Moored in the Custom House.

Special Correspondence of the Globe-Democrat.

NEW YORK, November 16.--Passing in Broadway, only a day or two since, a literary man who had a wide and apparently an established reputation when I was a mere boy, it occurred to me that very few persons would now recall his name, if they should hear it. Then I fell to thinking how many living authors there are in the East who enjoyed a large degree of fame twenty to thirty years since, but who at present are well-nigh forgotten. A number of them no doubt are supposed to be dead, and so far as any remembrance of the public is concerned, they are as dead as if they had been sleeping for a decade in Greenwood. One that writes anything that attracts attention must keep on writing just such things, or he will sink into oblivion. To preserve even the hope of a little reputation, one must be perpetually and laboriously at work, and even then his exertion may be without recompense.

THE VANITY OF REPUTATION.Even in so young a country as this, where literature has just begun to be cultivated, writers of both sexes, not yet old, have survived their fame, and appear to be veteran representatives of a misty past. Go into any of the second-hand book stores of Nassau street, and you will find scores on scores of volumes which were praised at the time of publication--only a few years ago--and of which their authors had high expectations, that have passed completely out of your mind. A book may be the only immortality; but the book that has any chance of immortality is not written more than once a century. It is very doubtful if any work has been printed in the New or the Old World, since the foundation of our Government, which will be remembered in 1976; and yet nearly every commonplace scribbler has a sneaking notion that he has said something that the world will be willing to keep. O, the vanity and egotism of man! How limitless, immeasurable, inexhaustible they are! It is well they are so, if human effort be desirable. Seeing ourselves as we are, how insignificant is the best and greatest of our performance, we should be reduced into eternal inactivity, and should adopt universal suicide as a relief from the supreme bitterness of self-contempt.

Every year that slips away leaves new literary ventures, launched with pride and promise, upon the beach, to be broken up by the returning waves on which they had hoped to ride. Full half the books issued this autumn will be forgotten next autumn, and those that are making a noise now, will, after a few seasons, be silent as the grave. Let me summon out of the limbo of oblivion some of the authors who still stalk the earth in a thick mist of unappreciation which they fondly imagine will one day be lifted. There is

CORNELIUS MATHEWS,as a sample. "Who is he?" I fancy many of your readers inquiring. "Never heard of him; when did he flourish. Certainly he is not alive." He is very much alive, and in abundant flesh, as one may see almost any day on Nassau street. He is not very old either--not quite sixty yet. He was a conspicuous literateur a quarter of a century ago, and his name and his writings figured in the newspapers prominently and with commendation. Born near here, and graduated at the New York University, he began his career at nineteen as a contributor, in prose and verse, to the American Monthly. He afterward appeared in the New York Review, Knickerbocker and other periodicals, and, when he was twenty-two, as the author of "Behemoth, a Legend of the Mound Builders," which was favorably received. He wrote a comedy--"The Politician"--presented without success, and a novel, "The Career of Puffer Hopkins," illustrating various phases of political life, which was widely read, and which caused him to be named after its hero. He produced several other stories and plays, one of them, "Witchcraft," a tragedy, praised by Margaret Fuller, which met with a fair reception, and enhanced his reputation.

He has been editor and assistant editor of different publications, long since gathered to their typographical fathers, and has for some time presided over the dull destinies of a professedly comic monthly, made up of clippings from all sources. This is said to yield him a fair revenue, as it ought to, for it is reputed to be much more tragic in its tone and tendency than "Witchcraft" ever was. Mathews writes little or nothing in these days. His fame rests in the past, to which he is fond of referring, speaking of himself not infrequently as "The American Dickens,"-- a title some of his injudicious admirers once bestowed on him.

Mathews is of liberal avoirdupois, very good-natured, pleasant, talkative, entertaining, with a strong inclination to believe that the present generation is not so good a judge of literature as the generation that has passed. He has vivid recollections of Washington Irving, Paulding, Poe, Willis, Clark, Seba Smith, N. P. Willis, Halleck, Malcolm Clarke, the mad poet, as he was styled, and many other authors of a by-gone period, and his reminiscences are extremely interesting.

One of the feminine antiquities which it will surprise many to know as still alive is

ELIZABETH OAKES SMITH,widow of Seba Smith, of Maj. Jack Downing fame. She used to be one of the most prominent feminine writers and lecturers in the country--in the days when women filled very little space in public life. Born in Maine (her maiden name was Prince), of distinguished Puritan ancestry, she was married at seventeen to Seba Smith, then a well-to-do citizen of Portland. Afterward, entering into land speculation, he lost all his property. His wife urged him to go into the woods of his native State, adopt frontier life, and rear their children as best they might. She was very anxious to do this, believing that they would be better able to contend with poverty in that way than any other. He was opposed, however, to his family enduring any such hardship. He proposed that they should come to New York, and thither they came, to live by their pens. Mrs. Smith had written anonymously and as an amateur before; but now she entered upon literature as a serious business, and no one who has ever attempted it will doubt that it is a very serious business.

THE BATTLE OF LIFE.She had versatility, though her talent was not remarkable, and both she and her liege found more employment than they had anticipated. Verses, stories, plays, essays and lectures followed in quick succession, and she became quite a favorite on the platform. She was one of the earliest advocates of women's rights, and a work, "Woman and Her Needs," published twenty-five years since, had many and earnest readers. Her husband died eight or nine years ago, and she has since been living very quietly on Long Island, not far from here, taking very small part in passing events. She has always felt a deep interest in all practical reforms, and has aided them with her voice and pen. The present excellent charity, the Newsboys' Home, is said to owe its beginning to a work of hers, "The Newsboy," in which she faithfully and pathetically depicted the hardships, the trials and the temptations to which he is exposed. Her latest contributions to literature were two serials printed in the Herald of Health, in 1870 and 1871.

Mrs. Smith is now seventy, and in delicate health. She had many troubles, and she has struggled hard to overcome or resist them, but with only partial success. Her hair is white as snow, and age, anxiety and suffering have told heavily upon her. But she still owns a strong will and stout heart and should be comforted for the thought that she has valiantly and stubbornly fought the battle of life.

HERMAN MELVILLEis an author who was once a great favorite, and deservedly such, though of late he has gone into the shade. He is one of the few writers of note who have been born in the metropolis, his grandfather, Thomas Melville, having been a member of the historic Boston tea-party. His boyhood was spent in the neighborhood of Albany, in this State, and of the Berkshire Hills, Massachusetts; but, seized with a love of the sea from reading marine novels, he ran away from home at eighteen and shipped before the mast on a vessel bound for Liverpool. He was not cured, as many lads have been, by actual experience; his passion for adventure was increased, instead, and when he had reached his majority he embarked as a sailor on a whaling ship, destined for the Pacific. After sailing for eighteen months, the behavior of the captain was so tyrannical and cruel that Melville and one of his messmates decided to desert. His plan was carried out at Nukahira, one of the Marquesas Islands. He had intended to throw himself on the hospitality of a friendly tribe of savages there, but, losing his way, he fell among the Typees, warlike natives, who held him prisoner for six months without offering to molest him, and, on the whole, treating him kindly. He was taken off by a boat from an Australian whaler, and conveyed to Tahiti. After wandering for two years, staying some time on the Society and Sandwich Islands, he returned home, arriving at Boston in the autumn of 1844.

THE WRITING MANIA.Two years later he published "Typel," a graceful, picturesque, interesting narrative of his experiences in Nukahira, which, owing to the sentimental coloring and artistically exaggerated character given to it, became very popular, and made for him a fine reputation. "Omoo," an account of his adventures in the South Seas, followed, and then "Mardi and a Voyage Thither," a philosophic romance, and "Redburn," founded on the incidents of his first voyage. Since then he has written seven or eight more sea tales and queer novels, or romances, not one of which has met with favor. His first book was by all odds his best, and each one that succeeded diminished in merit. He seems to be a striking instance of an author unable to sustain himself at his earliest level; he appears to have been for some time entirely written out, and he has come at last to recognize the fact himself.

When twenty-eight he married the daughter of Chief Justice Shaw, of Massachusetts, since when he has been around the globe on a whaling vessel, lived on a farm in New England, and pursued several vocations, without any decided success. His friends say he is not practical, which is undoubtedly true, as he has not made any money--having been some years in the Custom House here on a salary of $2000 to $2,500. He is a very pleasant, entertaining fellow, with a great deal of culture, with broad experience in travel and large acquaintance with men. He has many warm friends, though he goes very little into society, and is likely to stay in the Custom House until he is in demand by the undertaker. He is far from old, having passed by his fifty-ninth birthday last August.

SARAH JOSEPHA HALEis a veteran, indeed, being in her eighty-second year, and still able to work. Our grandmothers read her books, and thought them clever; but those dear old ladies had not the culture and critical taste that mark the present generation. Her native place is Newport, N. H., and her maiden name was Buell. In her nineteenth year she was married to David Hale, a lawyer of some local repute, with whom she studied for near eight years, when he died, leaving her with five small children, and less than $500 worth of property. With the necessity of supporting herself and family, she devoted herself to authorship. Her initial work was a small volume of poems, issued at Concord, and liberally purchased by the Freemasons, of which order her husband had been a member. Four years later she published "Northwood," a tale of New England, and soon after removed to Boston, where she became editor of The Ladies' Magazine, a monthly, and continued in that capacity until 1873.

The periodical was then untied with The Lady's Book, Philadelphia, and she was made its literary editor, a position she has held ever since. She is a rival of Bryant. She is very near as old as he, and has been connected with The Lady's Book, in its two-fold form, almost as long as he has been with the Evening Post. It is said, too, that she does work on it regularly even to the present day, while Bryant is asserted not to have written a line for his paper for four or five years; his connection with it being merely nominal.

REMUNERATIVE COMPILING.Mrs. Hale has published several volumes of verses, tales and dramas, of no extraordinary merit, and has made a number of compilations that have proved very profitable. Among these are "Flora's Interpreter;" The Ladies' Wreath," a selection from the women poets of England and America; "The Good Housekeeper," a manual of cookery; and a "Dictionary of Poetical Quotations"; all of which have had a large sale, yielding to the compiler some $50,000 or $60,000. Her principal work is "Woman's Record," a volume of nearly 1,000 pages, as it well may be, considering that it claims to include biographical sketches of all the distinguished women from ancient times down to the middle of the nineteenth century. If any man had done that, he would have been called a satirist. I will be gallant enough to say that such a record, to do justice to the sex, should be printed in 5,000 volumes.

DEUCEACE.Facsimile images of the St. Louis Globe-Democrat are available in Gale's 19th Century U. S. Newspapers. The Kansas City Research Center has a good long run on microfilm, starting in 1875.. For more than a decade, from 1876 until late in the 1880's, The St. Louis Globe-Democrat featured columns by New York correspondent "Deuceace," usually in the Sunday edition. The follow-up piece on "Authors in the Shade" in the Globe-Democrat for November 26, 1876 gave sketches of Charles F. Briggs and Alfred B. Street.

Years later Deuceace profiled Melville along with other supposedly self-educated writers in a column titled "Literature and College," published in the St. Louis Globe-Democrat on October 24, 1886.

... Herman Melville, once renowned as an author, though seldom mentioned of late, published more than forty years ago, "Typee" and "Omoo," delightful narratives of his adventures in the South Seas. He wrote other clever books, but none of them won so much reputation as his two first. He had no academic training. A native of this city, he conceived a romantic attachment for the sea, and at 18 shipped before the mast on a vessel bound for England. Two years later he embarked as a common sailor on a whaling vessel for the Pacific, cruising for eighteen months. Rebelling against the tyranny of the captain, he deserted with one of his shipmates; while lying off Nookaheeva, one of the Margnesas [Marquesas]. Losing his way, he roamed about until he stumbled into the Typee Valley. The warlike natives held him a prisoner for some months, but treated him kindly. He was taken off by an Australian whaler, and after many wanderings in Polynesia, returned to these shores. His writings show a thorough understanding of the force and delicacy of the English language, which he seems to have learned instinctively. He has published nothing for twenty years, having been much of that time buried in a department of the New York Custom House.The article by Deuceace on "American Magazine Editors" was reprinted from the St. Louis Globe-Democrat in The Journalist: Devoted to Newspapers, Authors, Artists and Publishers (November 19, 1887). There Deuceace sketched Melville's former editor at Putnam's magazine, the late Charles F. Briggs:

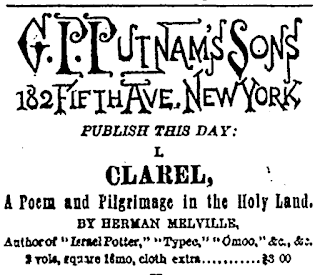

Briggs had an ample fund of humor and remarkable quickness of mind, but found it difficult, it is said, to form a staple judgment of any literary work. What he thought clever after breakfast, he would pronounce stupid before dinner, owing to his change of mood. Personal interviews with him often ended in serious disagreement, for he had a singularly irritating way, and was a great exception taker. Instinctively kind and ready to help any one needing help, he was constantly making enemies by his unpleasant manner. Parke Godwin is reported to have lacked punctuality and system. When he undertook to examine a MS. he would frequently mislay and forget it, and his engagements were kept or broken according to his recollection of them. Curtis was a delightful editor, but had few dealings with contributors. He thought that they could hardly be paid too much, and Godwin that they could not be paid too little. The second issue of Putnam's retained Briggs and Godwin; but Curtis was then intently occupied in making money to meet the liabilities he had incurred as a special partner of Dix, Edwards & Co., the firm to which the magazine had been transferred by Putnam during its first series. The revival of the magazine after the war was ill advised. It needed capital, and was not properly managed. Then articles were sent back after formal acceptance, and published after they had been declined. That was not the fault of any editor so much as the result of the periodical having no editor. The last year of Putnam's everything was by sixes and sevens.Whoever he was, Deuceace belonged to a crew of "special correspondents" that editor Joseph B. McCullagh (aka Little Mack) employed with great success after the merger in 1875 of the St. Louis Globe and Democrat. Considering the influential role of McCullagh's Globe-Democrat in the development of "mass-circulation journalism in America" the 1876 profile of Melville "in the shade" might be regarded as the start of Melville's amazingly popular reputation as a forgotten artist. Deuceace in November 1876 does not seem to know about the epic poem that was published in June, but who does?

|

| New York Evening Post - June 7, 1876 |

No comments:

Post a Comment