Thursday, December 31, 2020

Wednesday, December 30, 2020

Santa Claus Worldwide

Santa Claus Worldwide: A History of St. Nicholas and Other Holiday Gift-Bringers by Tom A. Jerman

Santa Claus Worldwide: A History of St. Nicholas and Other Holiday Gift-Bringers by Tom A. JermanMy rating: 5 of 5 stars

Santa Claus Worldwide distills the cheerful essence of Christmas from many sources and studies, old and new. In addition to his wide reading, author Tom A. Jerman has brought a wealth of personal experience and knowledge as a collector to the task of synthesizing the history and often bewildering variety of holiday gift-bringers. Jerman helpfully surveys ancient traditions (Roman Saturnalia) and models (Wotan/Odin, for example), as well as Christian figures like the Christkindl and myriad incarnations of jolly old St. Nick. Several chapters also offer new takes on familiar themes of previous Santa-studies. Of special interest to me in that regard are separate chapters on Washington Irving and the illustrated verses on "Old Santeclaus" as uniquely published in the 1821 Children's Friend. Without denying evident traces of Irving's comic History of New York on Clement C. Moore's iconic poem "A Visit from St. Nicholas," Jerman challenges the influential conspiracy theory that a few wealthy New Yorkers "invented" the American Santa Claus. With a collector's understanding of folklore and a lawyer's flair for arguing, Jerman makes a persuasive case for the historical-cultural evolution of Santa Claus, outside of and independent from any particular construction of Manhattan elites. This view expressly builds on previous work by Phyllis Siefker in Santa Claus, Last of the Wild Men (1997; 2006) and Gerry Bowler in Christmas in the Crosshairs (2016). Chapter 19 pays extra and well-deserved attention to William B. Gilley and illustrator Arthur J. Stansbury as co-creators of "Old Santeclaus."

I'm already finding this book valuable to have as a basic reference work when doing my own archival research. For instance, lately I discovered an 1841 newspaper reprinting of "A Visit from St Nicholas" with the alternative title, "Old Belsnickle." Say what? Well, as helpfully explained in several chapters (especially 3, 8, and 16), this Belsnickle or furry Nicholas has to be the Americanized Pelznickle, one of many protestant German gift-givers. Kriss Kringle similarly derives from the German Christkindl.

Santa Claus Worldwide fairly revels in the rich diversity of figures that symbolize and stimulate winter gift-giving. And it's loaded with wonderful pictures, too. I'm sure this exceptionally useful and readable volume of holiday history will make a great gift for 21st century Santas and Santa lovers everywhere.

Related post

- Champ Prevails - Review of The Fight for "The Night" https://melvilliana.blogspot.com/2023/12/champ-prevails-experts-foiled-truth.html

Sunday, December 27, 2020

Saturday, November 28, 2020

Benito Cereno in Louisville

|

| Lord Brougham in training for the opening of Parliament. via NYPL Digital Collections |

From the Louisville Daily Journal (Louisville, Kentucky), October 3, 1855:

PUTNAM’S MONTHLY FOR OCTOBER.—The October number of Putnam is a worthy representative of American periodical literature. Its contents are finely varied and are creditable specimens of substantial, instructive, and interesting literature….

... The story of “Benito Cereno” opens well, but rather hangs fire toward the close of its first part. But a lively denoument may redeem it.—There is interest ahead in it.The expression hang fire is a military metaphor for delayed action, like delayed ignition of gunpowder in firearms. To "hang fire" means

"to be slow in communicating, as fire in the pan of a gun to the charge."-- Noah Webster, 1828 American Dictionary of the English Language

In the 1855 magazine version of "Benito Cereno," the first installment closes with Melville's Delano musing on the possibly treacherous intentions of Don Benito. Delano fears the Spanish captain might be a murderous pirate. The American wavers, but his generous and trusting nature overcomes suspicion of a sinister plot against his life. Melville's narrative powder finally fires in the third installment, after Benito Cereno jumps into Delano's boat.

Another Kentucky reviewer had no expectation of an exciting finish in store. From the Louisville Daily Democrat, October 4, 1855:

"Benito Cereno," a tale, begun in the present issue, is a fanciful production, not having any great interest--very little force--and rather prosy. Some of the sentences are almost Broughamic in their length, indistinctness, and general construction.

Broughamic alludes to the discursive debating style of Henry Peter Brougham, the eminent Whig reformer and abolitionist who helped establish the Edinburgh Review. In 1828 Brougham delivered the longest speech ever in House of Commons, over six hours.

Courtesy of Google Books, Melville's "Benito Cereno" as it originally appeared in Putnam's Monthly Magazine Volume 6:- October 1855

https://books.google.com/books?id=i_FIAAAAcAAJ&pg=PA353&dq#v=onepage&q&f=false - November 1855

https://books.google.com/books?id=i_FIAAAAcAAJ&pg=PA459&dq#v=onepage&q&f=false - December 1855

https://books.google.com/books?id=i_FIAAAAcAAJ&pg=PA633&dq#v=onepage&q&f=false

Related post:

- Malay pirates in Benito Cereno and Trelawny

https://melvilliana.blogspot.com/2019/02/malay-pirates-in-benito-cereno-and.html

Monday, November 23, 2020

A One-footed or One-Legged American God

Guest post by John M. J. Gretchko

|

| From the Codex Fejérváry-Mayer via Mexicolore |

A One-footed or One-legged American God

Herman Melville explored the mythologies of many nations, from India to Egypt to classical Greece and Rome. Would he have ignored North American mythology? Chapter 36 “The Quarter-deck” of Moby-Dick suggests he may have significantly dabbled in it.

“Did you fixedly gaze, too, upon that ribbed and dented brow; there also, you would see still stranger foot-prints--the foot-prints of his one unsleeping ever-pacing thought”-- Moby-Dick Northwestern-Newberry Edition page 160.

The grandiose work, Antiquities of Mexico (1831-48) by Lord Kingsborough in nine monstrous volumes, each a labor to lift, holds drawings of this one-footed god from the Codex Fejérváry-Mayer, shown with an amputated right foot or leg. The Literary World of 7 April 1849 discloses that the Astor Library had acquired all nine volumes. Unfortunately Tezcatlipoca is not so identified in the text of Antiquities, nor do these volumes tell his story.

The manuscript Codex is held by the World Museum Liverpool.https://www.britishmuseum.org/collection/object/E_Am1902-0111-1 is accessible

“Thunder is used for lightning, or for a thunder-bolt, either originally through ignorance, or by way of metaphor, or because the lightning and thunder are closely united.”

Back in chapter 36, with a storm approaching, Ahab warns, “Stand up amid the general hurricane, thy one tost sapling cannot, Starbuck” (N-N page 164). Is Ahab alluding also to himself, as a metaphoric hurricane? Could the image of one sapling metaphorically represent or suggest a leg?

"both one-legged and a causer of hurricanes."

Works Cited

Burland, C. A. and Werner Forman. Feathered Serpent and Smoking Mirror. New York: Putnam, 1975.

Humboldt, Alexander von. Researches Concerning the Institutions and Monuments of the Ancient Inhabitants of America. Trans. Helen Maria Williams. 2 vols. London, 1814.

Kingsborough, Edward King, Viscount. Antiquities of Mexico: comprising fac-similes of ancient Mexican paintings and hieroglyphics. 9 vols. London, 1833-48.

Melville, Herman. Moby-Dick; or, the Whale. Edited by Harrison Hayford, Hershel Parker, and G. Thomas Tanselle. Volume 6 of The Writings of Herman Melville. Evanston and Chicago: Northwestern University Press and The Newberry Library, 1988.

Olivier, Guilhem. Mockeries and Metamorphoses of an Aztec God:Tezcatlipoca, “Lord of the Smoking Mirror.” Trans. Michel Besson. Boulder: U P of Colorado, 2008.

Séjorné, Laurette. Burning Water: Thought and Religion in Mexico. Translated by Irene Nicholson. Berkeley: Shambala, 1976.

Spence, Lewis. The Gods of Mexico. London: Unwin, 1923.

Tedlock, Dennis, translator and commentator. Popul Vuh: The Mayan Book of the Dawn of Life. Revised edition. New York: Touchstone, 1996.

Wednesday, November 11, 2020

Veterans Day Observance Arlington National Cemetery

Wednesday, November 4, 2020

Call me Frank

“Thank you for your frankness,” said Paul; “frank myself, I love to deal with a frank man. You, Doctor Franklin, are true and deep, and so you are frank.”

The sage sedately smiled, a queer incredulity just lurking in the corner of his mouth.

-- Israel Potter: His Fifty Years of Exile (1855); first printed in Putnam's Monthly Magazine - September 1854

Paul's genuine frankness contrasts with the more calculating and ambiguous behavior displayed by Benjamin Franklin. Hennig Cohen has noted how Melville's wordplay on the "frank" in Franklin looks forward to the ironic naming of Frank Goodman, the confidence-man's confidence man:

99.9-11 frankness . . . frank man . . . Franklin . . . frank

Paul Jones appears to be nothing if not frank, though Franklin, who appears at times to be less so, listens to his words with a lurking "incredulity" (99.12). Melville is once more turning to account the suggestiveness of a personal name. He is also anticipating the significant name, Frank Goodman, of The Confidence-Man (Chap. 29) who at times seems less than frank.

-- Annotations to Israel Potter: His Fifty Years of Exile, edited by Hennig Cohen (Fordham University Press, 1991) page 395.

Tuesday, November 3, 2020

Moby-Dick in New York correspondence of the Daily Pittsburgh Gazette

Sat, Nov 22, 1851 – Page 2 · The Pittsburgh Gazette (Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania) · Newspapers.com

Sat, Nov 22, 1851 – Page 2 · The Pittsburgh Gazette (Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania) · Newspapers.com

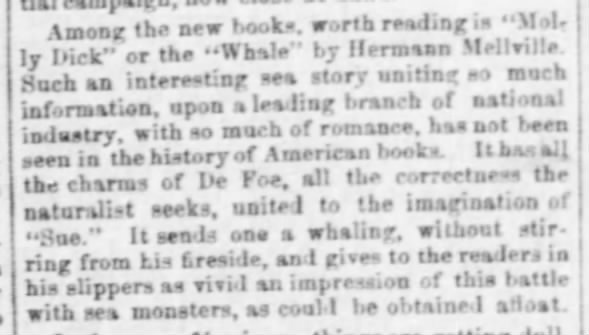

Letter from New York signed "C." and dated November 18th; from The Daily Pittsburgh Gazette, November 22, 1851:

Among the new books, worth reading is "Mol-ly Dick" or the "Whale" by Hermann Mellville. Such an interesting sea story uniting so much information, upon a leading branch of national industry, with so much of romance, has not been seen in the history of American books. It has all the charms of De Foe, all the correctness the naturalist seeks, united to the imagination of "Sue." It sends one a whaling, without stirring from his fireside, and gives to the readers in his slippers as vivid an impression of this battle with sea monsters, as could be obtained afloat.

Related post:

- Lady from Maine harpoons aggressor on train

https://melvilliana.blogspot.com/2021/09/lady-from-maine-harpoons-aggressor-on.html

Monday, November 2, 2020

After Winter: The Art and Life of Sterling A. Brown, 2009 | Online Research Library: Questia

One longs for Sterling’s satiric genius to be applied to current literary criticism, so much of which sags with horrendous jargon. Indeed, one quakes at the thought of his reaction to references to paragraphs being “unpacked,” to a subject being “interrogated.” One can easily imagine Sterling referring students to warehouses, police stations and to who knows what else. We may be sure that he would have a satiric antidote to the poison in the language of much criticism today.

Saturday, October 31, 2020

Tell Truth and shame the Devil

Via invaluable Or is it Devel? Either way, score this one for the Maestro Hershel Parker who correctly identified Hotspur's line from Shakespeare's Henry IV Part I long ago, without seeing the actual autograph book that contained it. Blindfolded, you might say. Henry A. Murray had misread Melville's inscription or heard it misreported as "Tell Truth and shame the dead." But Murray accepted Parker's better-informed guess and rightly predicted it would be confirmed some day, as revealed on pages 136-7 in Melville Biography: An Inside Narrative (Northwestern University Press, 2012). Parker thought Melville's contribution had been collected with autographs of other Berkshire celebrities in the 1850's, when Melville lived in Pittsfield. However, as shown above, Melville's inscription is dated March 2, 1882 in the autograph album of Lafayette Cornwell--offered at auction by Lion Heart Autographs just last week.

James Barron in the New York Times (October 18, 2020) portrays Cornwell as a somewhat elusive and mysterious autograph hound. Born in Saratoga Springs and schooled in Troy NY, Lafayette Cornwell found professional employment as a jeweler, watchmaker, railroad telegrapher and inspector. He moved west, then returned to New York from Canon City, Colorado in 1879. Cornwell began gathering autographs for his album in December 1880. From the "Item Overview" of Cornwell's unique collection on invaluable.com:

... Melville’s signature on page 114, and dated March 2, 1882, was written the same day as the signature of Edward Stiles Stokes, a notorious oilman who, in a jealous rage, murdered his business partner, “Diamond” Jim Fisk, but at the time was the well-respected proprietor of the fashionable Hoffman House hotel. Stokes’ signature, however, appears 12 pages after Melville’s and not on the same page as one would expect if the album had been assembled in chronological order. Did Cornwell meet the author of America’s greatest novel, “Moby Dick,” then eking out a living as a U.S. Customs inspector living on Manhattan’s East 26th Street, and then walk over to the nearby Hoffman House on Broadway between 24th and 25th streets and ask Stokes for his autograph? Or, perhaps, Melville was dining at the hotel and Cornwell recognized him?

Wed, Sep 15, 1926 – 1 · The Yonkers Herald (Yonkers, New York) · Newspapers.com

Monday, October 26, 2020

Sterling Allen Brown introducing Slim in Hell

|

| Sterling A. Brown via Kentake Page |

The Library of Congress has audio of Sterling Allen Brown reading his poems with comment in the Recording Laboratory, July 9, 1973:

Contents

From Southern road : Odyssey of Big Boy ; Long gone ; Checkers ; After winter ; Sister Lou ; Old man buzzard ; Ma Rainey -- Puttin' on dog -- Sporting Beasley (from Southern road) -- Slim in hell -- Old Lem -- Break of day -- Bitter fruit of the tree -- An old woman remembers -- Ballad of Joe Meek -- Strong men (from Southern road).

Transcribed by me below, Brown's great introduction to Slim in Hell which starts around 31:00:

One of my favorite characters is The Great Liar. In folk life of course the Great Liar is the Mark Twain yarn-spinner. To be called a great liar is a great praise. For instance I'm one of the greatest liars at Howard University, and that would include the President and the Board of Trustees and many of the faculty meetings. Ralph Bunche was a great liar. E. Franklin Frazier was a great liar. I imagine there's some great liars at other schools but I don't know them as well as I do Howard University. I'm sure there's some great liars in Congress. For instance I imagine that Senator Ervin is a great liar. This is an American type and in Negro life it's especially a noticeable type. And so I had a barbershop liar named Slim Greer and that was his actual name. He never lived long enough to sue me for royalties but I did not write this about him.

I wrote this poem in a class at Harvard in Anglo-Saxon where we were reading about Orpheus and Eurydice; now I know that's not an Anglo-Saxon story, but this was a group of stories that scholars prepared for us to learn the language before we started reading Beowulf. Now that's a long introduction. The only thing classical about it is that the dog in it is Cerberus. But I imagine, since Orpheus went to Hell, I imagine that my great tale-teller Slim Greer went to Hell. So I will now give you without any more exegesis or exodus or hell whatever they call it I will now give you Slim in Hell....

https://www.loc.gov/item/94838831/?

"Slim in Hell" is in The Collected Poems of Sterling A. Brown, edited by Michael S. Harper; reissued in 2020 by Northwestern University Press with a new foreword by Cornelius Eady and contributions from James Johnson and Sterling Stuckey.

Harper mentions Brown's expertise on Twain and Melville, and many other literary subjects, about five minutes into this 1994 conversation with Roland Flint on the poetry of Sterling Brown:

At 14:15 Harper reads "Slim in Hell."

Related posts:- Sterling Allen Brown on Benito Cereno

https://melvilliana.blogspot.com/2020/10/sterling-allen-brown-on-benito-cereno.html

- Sops for hell-hounds in Pierre

https://melvilliana.blogspot.com/2020/05/sops-for-hell-hounds-in-pierre.html

Friday, October 23, 2020

Jazz Age Benito Cereno

|

| Illustration for Herman Melville's Benito Cereno 1926 by E. McKnight Kauffer. Accession Number 1963-39-306 Cooper Hewitt, Smithsonian Design Museum |

https://www.si.edu/object/chndm_1963-39-306

and many other works donated by Mrs. E. Mcknight Kauffer.

Melville is represented by "Benito Cereno" and only "Benito Cereno" in the 1935 anthology of Major American Writers (New York: Harcourt, Brace and Company), edited by Howard Mumford Jones and Ernest E. Leisy. Available for 1 hour (after I'm done with it) on the great Internet Archive:

https://archive.org/details/majoramericanwri0000jone

The text in this neglected 1935 Benito Cereno follows The Piazza Tales version, but excellent footnotes also give significant variants from the first printing in Putnam's Magazine.

Via Google Books, Melville's "Benito Cereno" as it originally appeared in Putnam's Monthly Magazine Volume 6:

- October 1855

https://books.google.com/books?id=i_FIAAAAcAAJ&pg=PA353&dq#v=onepage&q&f=false

- November 1855

https://books.google.com/books?id=i_FIAAAAcAAJ&pg=PA459&dq#v=onepage&q&f=false

- December 1855

https://books.google.com/books?id=i_FIAAAAcAAJ&pg=PA633&dq#v=onepage&q&f=false

Wednesday, October 21, 2020

Sterling Allen Brown on Benito Cereno

Sterling A. Brown via BlackPast

Benito Cereno (1855) is a masterpiece of mystery, suspense and terror. Captain Delano of the Bachelor's Delight, discovering a vessel in distress along the uninhabited coast of Chile, boards her to render aid. He is interested in the many Negroes he finds on the decks: “ like most men of a good blithe heart he took to Negroes not philanthropically, but genially, just as other men to Newfoundland dogs." He is mystified, however, when the gamesome Negroes flare up in momentary rage, and especially by their continual clashing their hatchets together. Only when Don Benito, in desperation, escapes to Delano's ship, does the real truth dawn.

There had been a revolt on board the San Dominick; the Negro sailors and the slaves had killed many of the whites, and had kept the others alive only for their skill as navigators in order to reach a Negro country. The mutineers and revolters are overcome in a bloody battle, carried to Lima, and executed. The contrast between the reputed gentleness of Negroes "that makes them the best body-servants in the world," and the fierceness with which they fight for freedom is forcibly driven home. Certain Negroes stand out: Babo who, resembling a "begging friar," engineered the revolt with great skill and is almost fiendish in his manner of breaking down Cereno's morale; Francesco, the mulatto barber; Don José, personal servant of a Spanish Don; and Atulfa [Atufal], an untamed African chieftain, all filled with hatred for whites. Melville graphically pictures the slave mothers, "equally ready to die for their infants or fight for them”; the four old men monotonously polishing their hatchets; and the murderous Ashantees. All bear witness to what Melville recognized as a spirit that it would take years of slavery to break.

Although opposed to slavery, Melville does not make Benito Cereno into an abolitionist tract; he is more concerned with a thrilling narrative and character portrayal. But although the mutineers are bloodthirsty and cruel, Melville does not make them into villains; they revolt as mankind has always revolted. Because Melville was unwilling to look upon men as “Isolatoes," wishing instead of discover the "common continent of man,” he comes nearer the truth in his scattered pictures of a few unusual Negroes than do the other authors of this period.

-- Sterling Allen Brown, The Negro in American Fiction (Washington, DC, 1937) pages 12-13.

"Brown's analysis of Benito Cereno is the best I have seen...."--Joseph Schiffman, Critical Problems in Melville's Benito Cereno, Modern Language Quarterly volume 11 issue 3 (September 1950) pages 317-324 at page 323, footnote 23.

“Revolt on the San Dominick” in Phylon Volume 17, Number 2 (1956) pages 129–140. Conveniently accessible via JSTOR, www.jstor.org/stable/272586.

"is the very opposite of racist, that it is rather a subtle indictment of slavery, and a grim warning of the perils in store for those who, like Amasa Delano, ignore or dismiss its dangers."

https://books.google.com/books/about/The_Negro_in_American_Fiction.html?id=rXhBAAAAIAAJ

https://hdl.handle.net/2027/uc1.b4376173?urlappend=%3Bseq=20

Schomburg Center for Research in Black Culture, Jean Blackwell Hutson Research and Reference Division, The New York Public Library. "The Negro in American Fiction" The New York Public Library Digital Collections. 1937. http://digitalcollections.nypl.org/items/f0a11c90-080b-0135-79ca-0d6aeeb931ad

|

| Sterling A. Brown on Melville The Negro in American Fiction page 11 |

|

| Sterling A. Brown on Moby-Dick and "Benito Cereno" The Negro in American Fiction page 12 |

|

| Sterling A. Brown on "Benito Cereno" The Negro in American Fiction page 13 |

Related posts:

- Jazz Age Benito Cereno

https://melvilliana.blogspot.com/2020/10/jazz-age-benito-cereno.html

- Amasa Delano news and views

https://melvilliana.blogspot.com/2019/01/amasa-delano-news-and-views.html

- Sterling Allen Brown introducing Slim in Hell

https://melvilliana.blogspot.com/2020/10/sterling-allen-brown-introducing-slim.html

- Memory holes in the Broadview Benito Cereno

https://melvilliana.blogspot.com/2021/04/memory-holes-in-broadview-benito-cereno.html

Tuesday, October 20, 2020

Thursday, October 15, 2020

Toronto Globe notice of Moby-Dick

Looking for something else I finally ran across the favorable notice of Moby-Dick in the Toronto Globe. Reprinted by Hershel Parker in "Five Reviews Not in MOBY-DICK as Doubloon," English Language Notes (March 1972) pages 182-185 at 185.

From The Globe (Toronto, Ontario, Canada), November 29, 1851:

Disappointingly short on specifics, OK, but 100% positive. Put it on the board!!! Which ups the count of favorable reviews by one in our official 2020 Melvilliana census ofMOBY DICK, OR THE WHALE: by HERMAN MELVILLE; Author of Omoo, Typee, &c. New York, HARPER & BROTHERS. Toronto, A. H. ARMOUR & Co.

It is only necessary to say of this work that it is equal to any of Melville's former productions; by some it is thought even superior. This author is evidently not exhausted; he has yet stores within him untouched; although there is a close resemblance in his subjects, there is yet a difference in the handling, which gives constant variety. As a describer of the manners of the class of men he has chosen to depict, as a close observer and a striking limner of nature, Mr. Melville has few equals and no superiors among living authors, and there is a store of information upon all sorts of subjects, sacred and profane, landward and seaward, which surprises and delights one in a work of fiction. The volume is got up in capital style by Harper & Brothers.

- reviews and notices of Moby-Dick, 1851-2

https://melvilliana.blogspot.com/2020/02/moby-dick-widely-praised-in-1851-2.html

Tuesday, September 29, 2020

Melville's Reviewers: British and American, 1846-1891 by Hugh W. Hetherington, 1961 | Online Research Library: Questia

Tuesday, September 22, 2020

Confidence-Man in Yonkers

Thu, Apr 16, 1857 – 2 · Yonkers Examiner (Yonkers, New York) · Newspapers.com

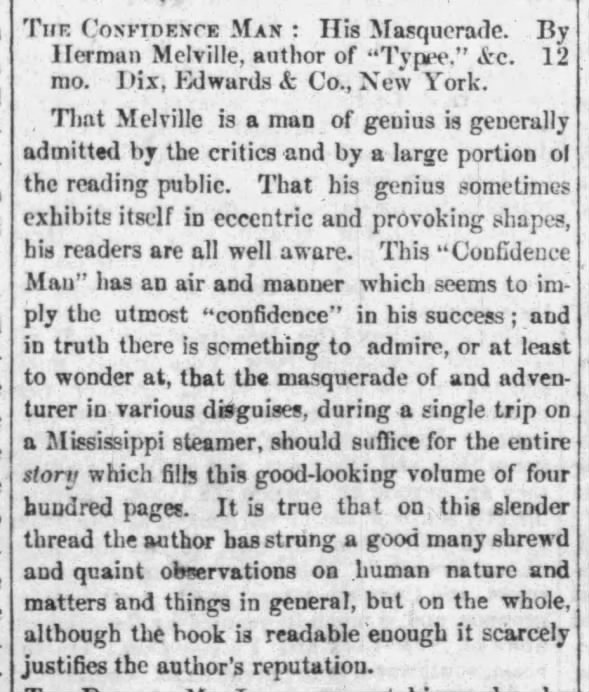

Thu, Apr 16, 1857 – 2 · Yonkers Examiner (Yonkers, New York) · Newspapers.comTHE CONFIDENCE-MAN: His Masquerade. By Herman Melville, author of "Typee," &c. 12 mo. Dix, Edwards & Co., New York.

That Melville is a man of genius is generally admitted by critics and by a large portion of the reading public. That his genius sometimes exhibits itself in eccentric and provoking shapes, his readers are all well aware. This "Confidence Man" has an air and manner which seems to imply the utmost "confidence" in his success; and in truth there is something to admire, or at least to wonder at, that the masquerade of and adventurer in various disguises, during a single trip on a Mississippi steamer, should suffice for the entire story which fills this good-looking volume of four hundred pages. It is true that on this slender thread the author has strung a good many shrewd and quaint observations on human nature and matters and things in general, but on the whole, although the book is readable enough it scarcely justifies the author's reputation.

Friday, September 11, 2020

H Melville in New York City

Guest post by John M. J. Gretchko

1846

1862

In chapter 92 of Moby-Dick, “Ambergris,” Melville facetiously speaks of curing the dyspepsia of a whale by administering “three or four boatloads of Brandreth pills.” |

| Brandreth's Pills National Museum of American History |

|

| via NYPL Digital Collections |

Hershel Parker comments in Herman Melville: A Biography Volume 2, 1851-1891 (Johns Hopkins University Press, 2002), page 515: “What his purpose was in going is not known.” Had Allan sent Herman to inspect and assess the state of Brandreth’s collateral? If the hotel had deteriorated, then the failure of the loan was Brandreth’s fault.

“The rooms are elegantly furnished---many of them in suites of communicating parlors and chambers, suitable for families and parties traveling together. Being kept on the European plan, guests may live in the most economical or luxurious manner. Meals served at all hours at the shortest notice.”

Monday, September 7, 2020

Friday, September 4, 2020

Can you make it rain harder?

"... it was like a scene from Moby-Dick."

--Bruce Rogers on Prince at the Halftime of Super Bowl XLI

Wednesday, September 2, 2020

BATTLE PIECES in the New York Weekly Journal of Commerce

|

| New York Weekly Journal of Commerce - October 4, 1866 via GenealogyBank |

HERMAN MELVILLE, well known in former years as the author of several very readable books of travel and fiction, makes his appearance again as a poet. HARPER & BROTHERS publish BATTLE PIECES AND ASPECTS OF THE WAR from his pen. He writes, as he always did, with spirit, vigor, and an admirable conception of the value of words. Some of his verses, which are exceedingly rude in structure, derive great force from that very rudeness. The volume is supplemented by a prose article, in which Mr. Melville urges an instant close of the quarrel between North and South, of which, at present, it looks as if the war were only the commencement.

Friday, August 28, 2020

Saints as Syrens

Conference paper read June 19, 2009 at the École Biblique in Jerusalem, Israel for the Seventh International Melville Conference, Melville and the Mediterranean:

SAINTS AS SYRENS:

THE OLD FAITH AND MELVILLE’S NEW MYTHOPOEIA

When the saints go marching in Clarel (1876) they exemplify the bravery of unbounded, unsophisticated faith—a heroism of credulity, as it were—and affirm the catholicity of Melville’s aesthetic vision. The Roman Catholic bent is pronounced, as William Ellery Sedgwick found (213-17), and structural, in that the “poem-pilgrimage” happens, as Hilton Obenzinger has reminded us, in liturgical time (76). The favorable treatment of Catholicism is examined by William Potter as part of Melville’s larger fascination with “the intersympathy of creeds.” In a similar vein, Brian Yothers credits the sympathy for Catholicism, which for conservative Protestants in Melville’s day could still mean Sympathy for the Devil, as the impetus for the “broader consideration of religious pluralism” in Clarel. The high regard “for saints and icons” has been recognized by Vincent Kenny (140), and Joseph G. Knapp notices the “special fondness for Catholic saints” in Melville’s correspondence (99).

But no critic has elaborated Melville’s affinity for saints as charmers, most obvious in versified views of Saints Louis, Francis, and Cecilia, and warm praise for virgin martyrs. Nehemiah is a “saint” but no siren. Even granting his credentials as a venerable wanderer, his lonely evangelism converts nobody. Catholic saints are the dangerous ones. Their seductive charms for a wayward Protestant like Rolfe (or Melville) are cheerfully confessed when Derwent the Anglican priest compares virgin saints to the sirens of classical mythology. Through Derwent, Melville contemplates a bold project of mythopoeia or “myth-making” in recommending Catholic “legends” as “the poet’s second mine,” a new treasure trove (better than the old Greek myths) awaiting versifiers in the sweet, non-sectarian future.

The French Biblical School makes a fitting place to consider Melville in relation to what he appreciatively called “the Old Faith.” Here we are doubly indebted to Dominicans: first, for the hospitality of this important center of Catholic biblical scholarship; and second, for the example of Henri–Dominique Lacordaire (1802-1861), who in the early 1840’s revived the formerly banned Dominican order in France. Melville’s sympathetic portrait of the Dominican in Clarel as “A champion of true liberty” draws heavily on the life and times of Father Lacordaire, memorialized by one biographer as “the tried champion of popular liberty” (Greenwell 130). As Dennis Berthold has suggested, the Dominican’s confidence in Rome oddly defies new strictures on the political authority of the Pope in recently unified Italy (359-366). And yet, the historical incongruity nicely registers the influence of Lacordaire, who died nearly a decade before the 1870 annexation of Rome. Lacordaire’s earlier activism in the cause of religious freedom, his memorable election in 1848 to the French National Assembly, his eloquence in the pulpit of Notre Dame, and even his rumored “austerities” in the exercise of monastic self-discipline—all widely reported in contemporary sources—gave Melville ample material for his characterization of the “Disinterested, earnest, pure / And liberal” exponent of Roman Catholicism.

What draws the Dominican into the narrative action of Clarel is a song, Ave maris stella, “Hail, thou Star of Ocean.” Rolfe leads off the Vespers hymn to Mary, in observance of a pilgrim rite at the Jordan River. Derwent and Vine join in. Hearing the hymn in three-part harmony, the Dominican strolls over for what Larry David would call a “stop and chat.” The French guest gets a canto (2.25) to make his case as a “staunch Catholic Democrat” for Roman orthodoxy: Catholicism appeals to the heart and offers supremely adaptable and enduring modes of consolation to suffering humans when protestant reform, scientific rationalism, and revolutionary politics fail to comfort.

Her [Rome’s] legends—some are sweet as May;Although Derwent never precisely defines “legends,” the context suggests the genre of saints’ lives, conventionally termed legendaries. His enthusiasm for saints’ lives as a literary goldmine is Melville’s. Writing to his brother-in-law on “Saturday in Easter Week” 1877, Melville praised “legends of the Old Faith” as “really wonderful both from their multiplicity and their poetry” (Correspondence 452). To illustrate, he commended the biography of St. Elizabeth of Hungary by the Count of Montalembert, the same “book of the sainted queen” which he had presented in October 1875 to his cousin Kate.

Ungarnered wealth no doubt is there....

When much that sours the sects is gone,

Like Dorian myths the bards shall own—

Yes, prove the poet’s second mine. (Clarel 2.26:86-93)

Derwent’s notion of Catholic legends as the “second mine” of future poetry likely derives from this passage in the introduction, as translated by Mary Anne Sadlier:

With regard to poetry, it would be difficult to deny that [popular religious traditions] contain an inexhaustible mine….a source of poetry infinitely more pure, abundant, and original, than the worn-out mythology of Olympus. (Life of Saint Elizabeth, pages 88-89)Along with the mine metaphor, Melville was impressed by the critique of “worn-out” Greek myths. Absent the scorn, Montalembert’s comment underlies Melville’s idea that for “multiplicity” and “poetry,” legendaries like the Life of St. Elizabeth “far surpasses the stories in the Greek mythologies” (Correspondence 452). Montalembert’s long introduction, an effusive overview of religion, politics, and art in the thirteenth-century, repeatedly extols the poetry in saints’ lives. By “poetry” he means chiefly the imaginative, romantic display of “charming incidents, illustrative of all that is freshest and purest in the human heart” (84). Replete with “ineffable sweetness” (90), tales of saintly bravery and piety reflect “the implicit faith” held by Christians of every class in medieval Europe. Nevertheless, the poetic charm of saints’ lives is also an inherent quality that exists “independent of their theological value” (88).

More debts to the Life of St. Elizabeth appear in the canto “Huts.” Melville’s main source, unidentified before now, for the ritual separation of lepers in the middle ages is chapter 24 on the heroine’s poverty and spiritual development. Elizabeth grew in humility and mercy through her irrepressible devotion to the poor and sick, lepers above all others. As Montalembert explains (296), believers in those days identified the leper with Christ on the authority of Isaiah 53:4: “…we have thought him as it were a leper, and as one struck by God and afflicted.” Melville adapts the verse and its medieval Christian exegesis in saying that Jesus “as a leper was foreshown” (1.25: 27).

From the solemn liturgy for the exile of lepers as described by Montalembert (294-298), Melville appropriated the Mass for the Dead, procession to the leper’s assigned dwelling place, ritual blessing of household utensils, and consecration of the hut with graveyard dirt. He borrowed the priest’s admonition, “Be thou dead to the world, living again to God,” as well as the closing benediction and provision of the leper’s hut with cross and alms-box. Melville’s “chance citation” (1.25: 79) of Sybella, sister to King Baldwin III of Jerusalem, again mimics Montalembert, who cited the Countess Sybella of Flanders as a medieval “heroine of charity” for her saintly ministrations to the lepers of Palestine (297).

In focused takes on saints, Clarel further explores the possibilities for poetry mined from Catholic legends. St. Louis and St. Francis receive the most significant attention. Louis IX (1214-1270) of France, thirteenth-century king and crusader, was legendary for lifelong piety. We might find more to mourn than praise in some deeds of the historical Louis, who oppressed Jews to war on Islam. His two crusades were both disasters in deserts. Ironically, however, the spectacular failures of Louis in Africa heighten his appeal for Melville as a figure of the hapless enthusiast. Rolfe, wanting the confidence to journey through the Judean wasteland, invokes St. Louis as an icon of blind faith in blank places: “King, who betwixt the cross and sword / On ashes died in cowl and cord … St. Louis! rise, / And teach us out of holy eyes / Whence came thy trust.” In ten lines Melville glosses the archetypal virtues of Louis: his humility, symbolized by the monastic garb of “cowl and cord”; his courageous heart, seemingly undaunted by suffering; and his childlike trust, baffling in the face of unrelieved misery (2.13: 1-10).

Francis of Assisi (1182-1226) combines the “simple faith” of Louis with charm and love. Devoted spouse of poverty and now patron saint of animals and ecology, Francis lived on alms and preached to the birds, yet somehow reformed his world. Two cantos in book 4 of Clarel focus on St. Francis. In canto 13, the saint illumines Salvaterra, the Franciscan guide in Bethlehem. The noble-looking novice reminds the pilgrims of the young St. Francis (4.13: 176), but his zeal alarms them. Rolfe is pained by visual evidence of Salvaterra’s ascetic lifestyle. That, or his too-fervent belief in miracles also bothers Derwent, who kindly hopes the lad will learn to relax.

In the next Bethlehem canto, Rolfe approves the role of Franciscans as custodians of Christian shrines, justified he argues by the uniquely Christ-like life of the original begging friar:

Through clouds of myth investing him--Melville’s phrase seraphic glow alludes to the reception of the stigmata as related in Bonaventure’s early Life of St. Francis. As Francis prayed on a mountain side for a physical experience of the crucifixion, his devotions became so heated they produced a “seraphic glow of longing” that transported him skyward (Salter 138). The crucified Jesus appeared to Francis in the likeness of an angel who imprinted on his body the five wounds of Christ’s Passion.

Obscuring, yet attesting him,

He burns with the seraphic glow

And perfume of a holy flower.

Sweetness, simplicity, with power! (Clarel 4.14: 69-73)

“Perfume” like “seraphic glow” marks the saint. But positive proofs of sainthood may overwhelm the mundane subject in divine attributes, “obscuring” the historical person while “attesting” the saint. Myths are all we know, “clouds of myths” to which Melville through Rolfe contributes. In times of spiritual dearth, as Northrop Frye argued, “poets have to hammer out their own archetypes…. hence the whole tradition of recreated mythology” (91). Here, myths that hallow Francis blur his ordinary humanness but confirm his best and most exemplary charms as Melville recreated them: “Sweetness, simplicity, with power!”

Derwent perceives the sweet humility of Francis as a feminine weakness, unbecoming in a “manly” man. Rolfe exalts the supposedly feminine side of Francis as entirely Christ-like. Derwent’s objection to sweet St. Francis betrays a gender bias or double-standard that Rolfe does not share, and forces Rolfe to defend compassion, sensitivity, and yielding love as redeeming Christian virtues. Rolfe rightly fears his case for Christian charity will seem “too orthodox” in its assumption of sinful human nature (4.15: 108). Rather than hear Rolfe preach on innate depravity, Derwent changes the subject. Still, Rolfe’s tribute to the “sweetness” of St. Francis echoes Derwent’s springtime simile, “sweet as May,” even if its inventor meant exclusively to honor women saints.

Of the women Cecilia enjoys the status of a favorite in Melville’s private calendar of saints. In Italy he had seen Raphael’s St. Cecilia, and he read and marked high critical praise for the painting in travel narratives, as Douglas Robillard has shown. And, as Robert K. Wallace reports, Melville owned a print of Cecelia after Domenichino. In Clarel Melville glances twice at Cecilia. Her stamped image, enthroned “'Tween angels with a rosy crown,” graces the cover of Rolfe’s hymnal. Attributes of Cecilia also convey the allure of Vine, whose uncanny “charm of subtle virtue” operates like

…that perfumed spellTimothy Marr reads these fragrant paradise flowers as a sign of Melville's "islamicist imagination," particularly evoking the cultural fascination with peris as beautiful and otherworldly female spirits. Another source for the scent of unseen “Paradise-flowers” is the section on Cecilia in the second volume of Anna Jameson’s Sacred and Legendary Art. As Jameson relates, Cecilia made a secret vow of chastity before marrying a wealthy Roman named Valerian. After converting and receiving baptism, Valerian found the maiden sanctity of his bride divinely approved by the presence of “an angel, who was standing near her, and who held in his hand two crowns of roses gathered in Paradise, immortal in their freshness and perfume, but invisible to the eyes of unbelievers” (585; emphasis mine). Chaucer’s “Second Nun’s Tale,” another possible source, lacks two words used by Melville, perfume and invisible, that are to be found in Jameson’s prose sketch of Cecilia, the first of “Four Great Virgins of the Latin Church” (along with Agnes, Agatha, and Lucia). Holy fragrance links Cecilia and Francis as bona fide saints, and reveals more than we knew of Melville’s reading in hagiography and art history.

Of Paradise-flowers invisible

Which angels round Cecilia bred. (Clarel 1.29: 24-26)

Jameson’s influential study of Christian iconography contains saints’ lives in abundance, with rich treatments of virgin martyrs. But Melville leaves them alone, mostly. “Arm ye, forearm!” warned Derwent, urging Rolfe to beware those virgins, lest their heroism convert him. The allure is real, the response ambiguous. Even Rolfe, the most catholically inclined of the non-Catholic pilgrims, stops short of acceptance. For one thing, outright conversion would terminate his job as philosophical rover, a seeker not a finder. And Rolfe like Melville is enamored of myths and rituals from many cultures and eras, not exclusively Roman Catholic ones. To follow the example of, say Cardinal Newman or Orestes Brownson would be to stop wandering, which truly Melvillean pilgrims never do. Had Melville gone Catholic and systematically devoted himself to writing sonnets on Jameson’s virgin saints he would not be Melville. He would be…

Commander William Gibson, United States Navy (1825-1887). In 1877, just one year after the publication of Clarel (1876), this unsung navy poet quietly turned out nine sonnets collectively titled “The Brides of Christ.” The whole sequence was first published in the Catholic World, and then reprinted with other verses on saints including Francis of Assisi in the 1881 collection, Poems of Many Years and Many Places. Gibson’s major source for sonnets on Dorothea, Cecilia, Agnes, Catherine, Margaret, Barbara, Agatha, Lucia, and Ursula was Jameson’s Sacred and Legendary Art. The cycle offers both the “multiplicity” and “poetry” that delighted Melville in “Legends of the Old Faith.” As Derwent preferred, Gibson keeps the legends “sweet as May,” and remarkably innocent of Church doctrine.

Sweetness, simplicity, with power. Fragrance and fire. These distinguishing features of Rolfe’s feminized aesthetic also distinguish Gibson’s virgin saints. Childlike simplicity defines Agnes and Margaret. The martyred Agnes inherits pastoral “meads of asphodel,” eternally preserving her employment as Christ’s shepherdess: “I lead his lambkins by my lily bell, / Where the pomegranates shade the softest sward.” No virgin saint, says Gibson, is “more meek and mild / Than sweet St. Margaret.” Sweet but strong, too: she’s a “Daisy” who overmastered the dragon Satan. Other “Brides of Christ” blaze, like Francis in Clarel, with fire and fragrance. Dorothea the “little martyr-maid” commissions an angel “with hair like odorous flame” to confound doubters with the fragrant testimony of flowers and fruit from Paradise. Barbara, though “soft as rosy May,” is also the “Christian Bellona,” as terrifying as the Roman goddess of battle. Proving her might, a cannon blast of “instant fire” incinerates her murderous father. Agatha’s power lives on in her veil, a relic strong enough to thwart the destruction of a convent by arresting molten lava in full flow from Mount Etna: “That Red Sea curdled by Saint Agatha!”

Fire and fragrance are again conjoined in “The Ecstasy of St. Theresa,” too daringly erotic perhaps for the Catholic World but appended to “The Brides of Christ” in Gibson’s 1881 volume. Theresa, the foremost of “unworldly yearners” in Clarel (3.1: 14-15), “swim[s] in flowers and flames,” overwhelmed in the sensuality of her longing for Christ as mystical lover. Inspired by the Bernini sculpture in Rome, the sonnet likens the “voluptuous agony” of Theresa’s desire to the yearning “of pagan maidens” for Apollo. Christ as Apollo, and St. Barbara as war goddess creatively associate Classical and Christian ideals, much in the same way that Melville’s Rolfe, as Walter E. Bezanson notes, habitually links Christian traditions with settings and motifs from Greek mythology (NN Clarel 817; 831).

As we have seen, the mythology of Olympus seemed a “worn-out” mine to Montalembert and Derwent after him. Earnestly working that first mine of Greek myths, William Gibson had published some fine longer poems in Harper’s magazine on Persephone, Apollo and the Sibyl, and Empedocles. In Jameson’s sainted virgins, however, he found a “second mine” of poetic inspiration. So Gibson proved Melville right about the literary gold in “Legends of the Old Faith.” When prophesied by Derwent, the new “Era” of verse-making from “the poet’s second mine” was surprisingly imminent. Versified saints’ lives by Commander William Gibson, USN, would triumphantly enact the catholic mythopoeia that Melville projected in Clarel but relinquished to unknown bards and better days.

Works Cited

Bercaw, Mary K. Melville’s Sources. Evanston, Illinois: Northwestern University Press, 1987.

Berthold, Dennis. “‘The Italian turn of thought’: Risorgimento Politics in Clarel.” Nineteenth-Century Literature 59 (December 2004): 340-371.

Frye, Northrop. Northrop Frye’s Notebooks on Romance. Ed. Michael Dolzani. Toronto: University of Toronto Press, 2004.

Gibson, William. “The Brides of Christ.” I. St. Dorothea; II. St. Cecelia; III. St. Agnes. The Catholic World 25 (June 1877): 420-421.

_____. “The Brides of Christ.” IV. St. Catherine; V. St. Margaret; VI. St. Barbara. The Catholic World Volume 25 (July 1877): 556-557.

_____. “The Brides of Christ.” VII. St. Agatha; VIII. St. Lucia; IX. St. Ursula. The Catholic World Volume 25 (August 1877): 701-702.

_____. Poems of Many Years and Many Places. Boston: Lee and Shepard; and New York: C. T. Dillingham, 1881.

Goldman, Stan. Melville’s Protest Theism: The Hidden and Silent God in Clarel. DeKalb: Northern Illinois University Press, 1993.

Greenwell, Dora. Lacordaire. Edinburgh: Edmonston and Douglas, 1867.

Jameson, Anna. Sacred and Legendary Art. Third Edition. 2 vols. London: Longman, Brown, Green, Longmans, & Roberts, 1857.

Kenny, Vincent S. Herman Melville’s Clarel: A Spiritual Autobiography. Hamden, Connecticut: Archon Books, 1973.

Knapp, Joseph G. Tortured Synthesis: The Meaning of Melville’s Clarel. New York: Philosophical Library, 1971.

Marr, Timothy. The Cultural Roots of American Islamicism. Cambridge University Press, 2006.

Melville, Herman. Clarel: A Poem and Pilgrimage in the Holy Land. Ed. Harrison Hayford, Hershel Parker, and G. Thomas Tanselle. Evanston and Chicago: Northwestern University Press and the Newberry Library, 1991.

_____. Correspondence. Ed. Lynn Horth. Evanston and Chicago: Northwestern University Press and the Newberry Library, 1993.

Montalembert, Charles Forbes René. The Life of St. Elizabeth, of Hungary. Translated by Mary Hackett. Introduction translated by Mrs. J. Sadlier. New York: Sadlier, 1870.

Obenzinger, Hilton. American Palestine: Melville, Twain, and the Holy Land Mania. Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1999.

Parker, Hershel. Herman Melville: A Biography. 2 vols. Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press, 1996 and 2002.

_____. Melville: The Making of the Poet. Evanston, Illinois: Northwestern University Press, 2008.

Potter, William. Melville’s Clarel and the Intersympathy of Creeds. Kent, Ohio: Kent State University Press, 2004.

Robillard, Douglas. Melville and the Visual Arts: Ionian Form, Venetian Tint. Kent, Ohio: Kent State University Press, 1997.

Salter, Emma Gurney, ed. Life of Saint Francis by Saint Bonaventura. London: J. M. Dent, 1904.

Sealts, Merton M. Jr. Melville's Reading: Revised and Enlarged Edition. Columbia: University of South Carolina Press, 1988.

Sedgwick, William Ellery. Herman Melville: The Tragedy of Mind. Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 1944. Reprinted, New York: Russell & Russell, 1962.

Wallace, Robert K. “Melville’s Prints and Engravings at the Berkshire Athenaeum.” Essays in Arts and Sciences 15 (June 1986): 59-90.

Yothers, Brian. “‘Remember Hospitable Rome’: The Allure of Democratic Catholicism in Herman Melville’s Clarel.” Unpublished paper, presented at the 18th Annual Conference of the American Literature Association (Boston, MA), 24 May 2007.

_____. The Romance of the Holy Land in American Travel Writing, 1790-1876. Aldershot, Hants, England and Burlington, Vermont: Ashgate, 2007.

Related posts

- Lacordaire, model for Melville's Dominican in Clarel

https://melvilliana.blogspot.com/2011/08/lacordaire-model-for-melvilles.html

- Clarel's name

https://melvilliana.blogspot.com/2019/11/clarels-name.html

- Miracle roses in Rosary Beads, borrowed from the real LIFE OF SAINT ELIZABETH

https://melvilliana.blogspot.com/2022/09/miracle-roses-in-rosary-beads-borrowed.html

- On Substack, Saint Elizabeth's Miracle of Roses in Melville's "Rosary Beads"

https://open.substack.com/pub/melvilliana/p/saint-elizabeths-miracle-of-roses?