Voiced by a victor, Melville's Civil War poem Gettysburg (subtitled "The Check.") offers a patriotic post-war take on the awful battle--not a conclusive Win from this perspective but the terribly costly turning point that curbed the progress of "impious" invaders. As portrayed here it's Good v. Evil all the way through. Figuratively, Union-Israelites backed by the omnipotent Lord of Hosts versus Confederate-Philistines, worshippers of the false god Dagon. Melville's speaker, like his presumed audience of loyal Northern readers, remains untroubled by any uncertainty or moral ambiguity about which side was right in the American Civil War. Like the idol of ancient pagans, the South's unholy cause of Rebellion was foredoomed to fall. The strong pro-Union stance is still evident in the final stanza of "Gettysburg," particularly in Melville's closing allusion to the formal ceremony of July 4, 1865 in which the cornerstone was laid for the Soldier's National Monument to be placed in the recently established National Cemetery. Melville's own prose note enables future readers and commentators to get his drift by explicitly identifying the historical referent in the last two lines of verse:

On the 4th of July, 1865, the Gettysburg National Cemetery, on the same height with the original burial-ground, was consecrated, and the corner-stone laid of a commemorative pile.

-- from Melville's Notes to Battle-Pieces (New York, 1866) page 249.

|

Laying the Cornerstone of the Soldiers' Monument at Gettysburg, July 4, 1865.

Harper's Weekly - July 22, 1865 - page 453 |

Neglect of Melville's note and the historical context it supplies (not to mention the bad influences of Mikhail Bakhtin and Garry Wills) allowed David Devries and Hugh Egan to imagine a generous "inclusiveness" in Melville's forecast that "every bone / Shall rest in honor" at the new National Cemetery.

Devries, David and Hugh Egan. ""Entangled Rhyme": A Dialogic Reading of Melville's Battle-Pieces." Leviathan, vol. 9 no. 3, 2007, p. 17-33. Project MUSE muse.jhu.edu/article/492809.

In their 2007 Leviathan essay, Devries and Egan assert that Melville's "non-specific and general" phrase every bone applies equally to "Confederate and Union dead," poetically mingling their remains in a transcendental gesture that looks forward to a more enlightened and ultimately trans-national future. Equally unconcerned with the details of Melville's prose note, Stanton Garner had the same idea, interpreting Melville's monument before and after transfiguration as a unifying symbol that humanely

"honors all the dead who lay together on the field."

-- The Civil War World of Herman Melville (University Press of Kansas, 1993) page 248.

Just the other day I heard the same take on "every bone" proposed in a thoughtful discussion of "Gettysburg" and other poems from Battle-Pieces on the Critical Readings podcast.

Thankfully, Jonathan Alexander Cook has provided a needful history lesson, reminding us that cemetery and monument specifically and exclusively honor "all the Union dead at Gettysburg" and "their sacrifice for the preservation of the Union":

The individual "warrior-monument" in Melville's poem becomes synonymous with all the Union dead at Gettysburg, whose graves now have an "ampler" meaning with the civic rituals ("Soldier and priest with hymn and prayer") performed at the national cemetery to honor their sacrifice for the preservation of the Union.

-- "Melville and the Lord of Hosts: Holy War and Divine Warrior Rhetoric in Battle-Pieces" in This Mighty Convulsion, edited by Christopher Sten and Tyler Hoffman (University of Iowa Press, 2019) pages 135-152 at pages 142-3.

Looking further into the relevant background as reported in Melville's time and ours, I think even more might be said about both the original "warrior-monument" and later "civic rituals" to which Cook points. Hopefully, closer examination of the historical record will enable a better understanding of Melville's poem "Gettysburg," the last stanza in particular:

Sloped on the hill the mounds were green,

Our centre held that place of graves,

And some still hold it in their swoon,

And over these a glory waves.

The warrior-monument, crashed in fight,

Shall soar transfigured in loftier light,

A meaning ampler bear;

Soldier and priest with hymn and prayer

Have laid the stone, and every bone

Shall rest in honor there.

First, about the original "warrior-monument" as Melville termed it, "crashed in fight." Melville explained the reference in the first part of his note to "Gettysburg":

Among numerous head-stones or monuments on Cemetery Hill, marred or destroyed by the enemy's concentrated fire, was one, somewhat conspicuous, of a Federal officer killed before Richmond in 1862.

As shown previously on Melvilliana

the "warrior-monument" in Melville's poem refers to the damaged grave stone of Sergeant Frederick A. Huber (1842-1862) at Evergreen Cemetery, adjacent to the National Cemetery at Gettysburg. To this day, Gettysburg historians and tour guides continue to visit what's left of Sgt. Huber's grave marker.

Without identifying the fallen soldier by name, Melville's note to "Gettysburg" correctly gives the place and year of his death. Frederick Huber, First Sergeant Company F of the

Twenty-Third Pennsylvania Volunteer Infantry aka

Birney's Zouaves was killed at Fair Oaks, Virginia in the

Battle of Seven Pines on May 31, 1862. A number of contemporary newspaper accounts relate the sad story of Sgt. Huber's death in battle and the damage to his tall grave marker in Evergreen Cemetery one year later. One of the best, by a friend and former classmate, was signed "W." and published in the Cleveland

Weekly Plain Dealer on December 16, 1863.

|

Cleveland, Ohio Weekly Plain Dealer

December 16, 1863 |

A Bit of Sad Romance.

GETTYSBURG, Dec. 3, 1863

EDITOR PLAIN DEALER--I have just been glancing over a letter of "G. H.," written to you from this place. Much interested as I was in his account, pardon me if I add a few words to one paragraph. It is in reference to the broken tombstone of a Union volunteer.

It was at Fair Oaks, and not at Mill Spring, that FRED. A. HUBER, Orderly Sergeant of Co. F, 23d Regiment Pennsylvania Volunteers, gave up his life for the glorious Union. Poor FRED! I knew him well. We were college mates and friends, in the years that are gone, and a braver, truer heart than his never beat. From the striking of the first war note, his heart was in the field, but family reasons for a long time held him at home. When he did make up his mind to go, it was after serious and sober reflection, and from a stern sense of duty. He went from sheer patriotism. To prove this it is only necessary to say that he rejected the offer of a Lieutenancy in a Pennsylvania Cavalry Regiment and enlisted as a private in BIRNEY's 23d. Well instructed in the duties of a soldier--for he had for months made military matters a study--he was offered the post of Orderly Sergeant, but with native modesty rejected it, preferring to win his laurels. Well read in the theory of medicine--almost ready to practice--he was offered a post of comparative safety about the hospital--if I am not mistaken, that of hospital Steward--but his answer was: "I am able-bodied, strong, young, and fit to carry a musket; my place is in the ranks." Through the long winter in front of Washington I would receive letters from him, every one praying for a fight.

At length came the move on the Peninsula, and in his first charge FRED fell, shot through the lungs. His friends would have carried him off, but his practiced soul--cool even amid the horrors of battle and death--knew the wound was mortal, and told them to desist. "Tell my parents that I died for my country," were the last words mortal man ever heard him utter.-- When the roar of battle was over--when the thunder of artillery and the rattle and crash of musketry had ceased--when the foe was vanquished and the field of Fair Oaks was won, they found him where they had left him--dead on the field of battle. They brought him home, and as I helped to consign his corpse to its final resting place, I could only murmur, "If he had only lived!"

When our thinned and mangled lines went grimly back before the surging charge of the rebel hosts, and the fortunes of the day looked red and lowry, I watched the flashing of the artillery as it kept guard around the tombs of the departed, and wondered then if amidst the storm of battle I could reasonably expect FRED's tomb stone to remain untouched. Five days later I found it almost the only one destroyed. Gallant soldier! He needs no monument, for he lives in the hearts of his friends.

W.

Regarded as a poetic device, Melville's conceit in the last stanza of "Gettysburg" is that the stricken "warrior-monument" to the sacrifice of one individual war hero will some day in the not too distant future be "transfigured" into a grander symbol of victory that honors all Union soldiers who died for their country.

In this context, civic honors may only be accorded to those who made the ultimate sacrifice and thus gave what

Lincoln at Gettysburg famously called "the last full measure of devotion" to save the United States of America. The Soldiers' National Cemetery continues to be introduced as

"the final resting place for more than 3500 Union soldiers from the Battle of Gettysburg."

Considered together the carefully arranged headstones demonstrate "the magnitude of the loss and the cost to preserve our Democracy." -- Gettysburg Foundation - Gettysburg National Cemetery

In his chosen role as national bard, Melville could and did portray the kinship and common humanity of boy-soldiers on both sides of the divide. As required by setting and theme, he might fittingly respect, lament, mourn, or remember any one of the Confederate dead. Characteristically, Melville sympathizes most readily with grieving widows, mothers, and sisters. Grief felt and expressed in the defeated South over loved ones killed in the war is natural, of course--and no less holy than grief experienced in Northern families, as Melville insists in the prose Supplement to Battle-Pieces:

The mourners who this summer bear flowers to the mounds of the Virginian and Georgian dead are, in their domestic bereavement and proud affection, as sacred in the eye of Heaven as are those who go with similar offerings of tender grief and love into the cemeteries of our Northern martyrs.

While heartfelt grief must be equally "sacred in the eye of Heaven" the expression of that grief here on earth normally occurred in separate cemeteries. With the fall of Richmond, the side of secession and slavery lost. For all of his generous forbearance and post-war regard for the losers as countrymen, it could never be in Melville's power to bestow national honor on the remains of fallen Confederate soldiers.

"Each column is pannelled, and bears the names of the eighteen States whose troops have shed their blood upon the consecrated field. The dead are gathered in circular rows, those of each State in separate lots, and the names of all identified carved upon the curb. The unknown dead are gathered to themselves and form a large proportion of the heroes who sleep. Thus far, it is estimated, that 3,800 soldiers rest within the enclosure. The Confederate dead sleep strewn apart in the valleys and on the hills."

-- "The Gettysburg Memorial," Baltimore Sun, July 6, 1865.

The distinction of honorable rest at Gettysburg National Cemetery could not be expanded to include Rebels without diminishing the honor. Inevitably, bones of Confederate dead did get buried with those of Union soldiers--by accident. As Sarah Kay Bierle explains in her 2016 blog post on

Dead Confederates at Gettysburg:

"Confederate soldiers were not reburied in Gettysburg National Cemetery. Samuel Weaver – the man in charge of overseeing the disinterment of original graves to move the bodies to the new cemetery – was zealous in his goal not to have a single Rebel buried alongside Union men in the national cemetery. (We now know that at least two Southern soldiers are buried in the national cemetery)."

In his formal statement of March 19, 1864, reprinted in

Soldiers' National Cemetery at Gettysburg, Pennsylvania (Indianapolis, 1865), Samuel Weaver attested "that there has not been a single mistake made in the removal of the soldiers to the Cemetery, by taking the body of a rebel for a Union soldier."

|

Soldiers' National Cemetery at Gettysburg, Pennsylvania

Indianapolis, 1865

|

The whole point of the project, however imperfectly conducted, was to identify bodies of Federal heroes from every State of the Union and bury them with honor. In the words of

Michael E. Ruane, "no Confederate could rest" in the new National Cemetery (Washington

Post, September 13, 2013).

Despite the practical difficulties of identifying the dead, the contrast in treatment of Union and Confederate bodies could hardly have been sharper. The notion that bones of dead Rebels would be honored in the new National Cemetery ignores the dramatic, lasting, and eventually embarrassing disregard for killed Confederates at Gettysburg.

With the approach of planting season in 1864, Pennsylvania farmers were ready to plough the battlefield under, corpses and all. From the Annapolis Gazette of April 7, 1864:

THE REBEL DEAD AT GETTYSBURG.

From evidence developed to the workmen and others engaged in removing the dead bodies on the battle-field, they are fully convinced that not less than seven thousand Rebels lost their lives in this conflict, the bodies of whom are still there.-- In one space of three acres was found three hundred and twenty-five confederates slain; and elsewhere, in a single trench two hundred and fifty more. A considerable portion of the battle-ground is likely to be ploughed up this spring and summer, by farmers owning it, preparatory to planting corn and other grain. As a matter of course the Confederate graves must be obliterated, and the trenches which now indicate their places. There is a strong desire with the people, in respect to humanity, to have these bodies, though of the enemy, respectably and decently put away in some inclosure where they may not be disturbed. Our common humanity should impel us to such a step.-- Gettysburg Star and Banner

In the summer of 1865 "CASTINE," a special correspondent of the Sacramento Daily Union, noted the contrast in reporting on "The Graves of Gettysburg":

Several years ago the citizens of Gettysburg laid out upon the summit of what is now Cemetery Hill a beautiful burial ground, adjoining which is the National Cemetery, where lie buried the remains of those who fell here fighting for the Union. The rebel dead are buried in spots all over the field; but here all of the Union soldiers, representing nearly every loyal State, are gathered. -- Sacramento, California Daily Union, July 14, 1865.

To the same effect, another observation of "Gettysburg Battle-Field" two years after "the terrible conflict" there appeared in a letter from regular correspondent "CYMON," printed in the New York Times on July 10, 1865:

"Reopened graves on the easterly slope of the hill mark where our gallant dead were first buried, now exhumed and interred with honor in the nation's cemetery. Down in the ravine where the rebel line of battle issued are mounds, grass-grown, unmarked and untouched, where the enemy's dead were buried, a trench their sepulchre, an army blanket their winding-sheet, and the sighing of the forest breezes their only requiem."

When the Soldiers' Monument was finally installed in July 1869, three years after Melville's poem "Gettysburg" first appeared in Harper's New Monthly Magazine, featured speakers at the formal ceremony noted and variously deplored the continuing neglect of the remains of fallen Confederate soldiers. Henry Ward Beecher, George G. Meade, and Oliver P. Morton all remarked on the pitiful sight of these shallow, unmarked mounds and trenches. Gen. Meade made a strong plea for the decent burial of "the bones of the Rebel dead." Elsewhere, obviously, not in the National Cemetery at Gettysburg.

From the New York Semi-Weekly Tribune ("Gettysburg. / The National Monument. / Dedication Services") of July 2, 1869:

"Then Henry Ward Beecher uttered a solemn prayer in the large, and loving, and fervent words so familiar from his lips. Gen. Meade said a few earnest words, recalling the history of the place, recognizing the courage, and self-sacrifice, and patience that made this day possible, and feelingly pleading that the bones of the Rebel dead should be gathered, and kindly and decently interred."

|

| New York Journal of Commerce - July 2, 1869 |

There is one subject, my friends, which I will mention now and on this spot where my attention has been called to it, and in which I trust my feeble voice will have some influence. When I contemplate this field I see here and there, marked with hastily dug trenches, the graves in which the dead with whom we fought are gathered. They are the work of my brothers in arms the day after battle. Above them a bit of plank indicates simply that these remains of the fallen foe were hurriedly laid there by the soldiers who met them in battle. Why should we not collect them in some suitable place? I do not ask that a monument should be erected over them. I do not ask that we should in any way indorse the course of their conduct, or entertain other than feelings of condemnation for their course. But they are dead; they have gone before their Maker to be judged. In all civilized countries it is the usage to bury the dead with decency and respect, and even to fallen enemies respectful burials are accorded in death. [Applause.]

I earnestly hope this suggestion may have some influence throughout this broad land, for this is only one among a hundred crowded battle-fields. Some persons may be designated by the Government, if necessary, to collect these neglected bodies and bury them without commemorative monuments, but simply indicate that below sleep the misguided men who fell in battle for a cause over which we triumphed.... --Boston Daily Evening Transcript, Friday, July 2, 1869.

Without going as far as General Meade before him in urging their removal and proper burial, featured orator Oliver Perry Morton of Indiana called attention to the plainly unhonored "graves of the rebel dead":

|

New York Commercial Advertiser - July 2, 1869

|

"In the fields before us are the graves of the rebel dead, now sunk to the level of the plain, "unmarked, unhonored, and unknown." They were our countrymen, of our blood, language, and history. They displayed a courage worthy of their country, and of a better cause, and we may drop a tear to their memory. The news of this fatal field carried agony to thousands of Southern homes, and the wail of despair was heard in the everglades and orange groves of the South. Would to God that these men had died for their country and not in fratricidal strife, for its destruction. Oh, who can describe the wickedness of rebellion, or paint the horrors of civil war!" --reprinted in John Russell Bartlett, The Soldiers' National Cemetery at Gettysburg (Providence, Rhode Island, 1874) page 91. A digitized version of this 1874 volume is accessible online courtesy of the Internet Archive:

https://archive.org/details/soldiersnational00bart/page/n7/mode/2up

Henry Ward Beecher the influential Congregational minister was reportedly "shocked at the exposed remains and robbery of the shallow graves and trenches in which the Southern slain were not decently buried, and whose proper reinterment has never been cared for since." As quoted in the Alexandria, Virginia Gazette for October 28, 1869, Rev. Beecher

"... refers to the fact that "We disburden the gibbet tenderly and give sepulture to murderers" and asks "Can it be possible that a great and generous nation will much longer suffer the Confederate dead to lie disheveled in such utter and contemptuous neglect?"

|

| Alexandria, Virginia Gazette - October 28, 1869 |

Three years after the first appearance of Melville's "Gettysburg" in print, the "disheveled" remains of dead Confederate soldiers lay in "utter and contemptuous neglect." Mistakes excepted, nobody had any idea of deliberately honoring dead Rebels there in the new National Cemetery at Gettysburg. To receive any sort of honors, remains of fallen Rebels first would have to be disinterred and sent home.

Ladies’ Memorial Associations across the South formed the resolution to raise money, find helpful connections, disinter the Confederate soldiers, and re-bury them in Southern cemeteries. It was clear the Confederate dead were not welcome in the Gettysburg National Cemetery, so the ladies decided to bring their fallen back to Southern soil.

-- Sarah Kay Bierle, Dead Confederates at Gettysburg via gazette665.com

Being inclined to philosophize, Melville when he wanted to could certainly take the long view of things. Differently framed, against the backdrop of classical art and mythology, ancient history, the wisdom of Solomon, geologic time, or the Cosmos, the honors reserved for Union dead might seem a rather trivial affair. To be sure, "Gettysburg" the poem begins in Bible history with Dagon as emblem of unrighteous rebellion. From there, however, the poem rehearses "three waves" of Pickett's Charge on July 3, 1863 before moving on to the 1865 proceedings conducted by "soldier and priest," laying the cornerstone of the Soldiers' Monument.

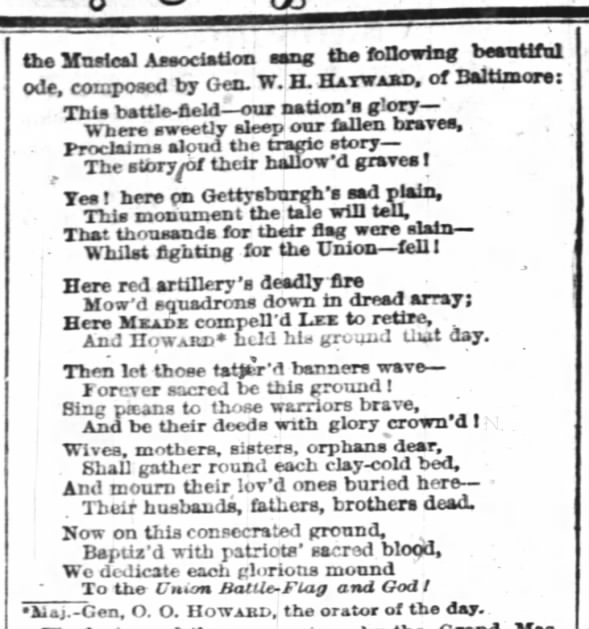

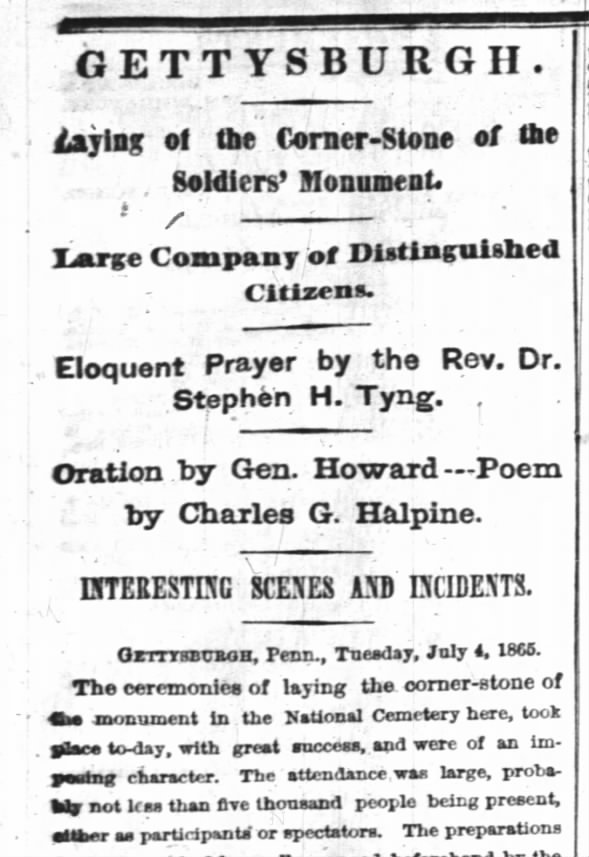

As affirmed in Melville's note to "Gettysburg," the poet's present-day in the last stanza must be just after the time of that

imposing 1865 ceremony. Two participants, General William H. Hayward and Reverend

Stephen Higginson Tyng could be seen as real-life counterparts of Melville's unnamed "soldier and priest." More on them in another post, hopefully. After the singing of Gen. Hayward's

Monumental Ode by the National Union Musical Association of Baltimore, the prayer by Rev. Tyng, and the ceremonial laying of the corner stone by

Pennsylvania Freemasons, General

Oliver O. Howard delivered the featured oration. (Also part of the formal program, the reading of a

letter from President Andrew Johnson who was ill at the time and unable to attend. Conciliatory language in the President's message may have influenced some of the words and the tone of Melville's

prose supplement to Battle-Pieces.) After Gen. Howard's well-received speech came a reading of the poem composed for the occasion by

Charles Graham Halpine aka "Private Miles O'Reilly." The following lines of which seem directly relevant to the imagery and symbolism at the end of Melville's "Gettysburg":

To-day a nation meets to build

A nation's trophy to the dead,

Who, living, formed her sword and shield,

The arms she sadly learned to wield,

When other hope of peace had fled;

And not alone for those who be

In honored graves before us blest,

Shall our proud column broad and high,

Climb upward to the blessing sky,

But be for all a monument.

An emblem of our grief as well

For others, as for these, we raise;

For these beneath our feet who dwell,

And all who in the good cause fell,

On other fields in other frays.

-- One Hundred Choice Selections in Poetry and Prose, edited by Nathaniel K. Richardson (Philadelphia, 1866) pages 46-49.

Herman Melville could have found all of this "exquisite poem" in the July 15, 1865 issue of Harper's Weekly, printed under the heading "Thoughts of the Place and Time." Accessible online courtesy of the great Internet Archive:

Colonel Halpine's poem illustrates the transforming effect then expected of the Soldiers' Monument, yet unveiled but already perceived as emblematic of shared national grief. The "ampler meaning" forecasted in Melville's poem similarly alludes to the unifying function of the still-forthcoming monument. As national symbol, the lofty Soldier's Monument memorializes all the Union dead--not only those soldiers buried State-by-State in the Gettysburg National Cemetery, but

"all who in the good cause fell,

On other fields in other frays."

Including poor Fred Huber, who gave up his life for the glorious Union, and whose broken tombstone may still be found in Evergreen Cemetery.

Related posts: