On January 5, 1914 the New York

Sun published a letter signed "M. W. Montgomery" that questioned the usual attribution of "A Visit from St. Nicholas" to Clement C. Moore and promoted the case for Henry Livingston, based on Livingston family lore. The writer was Mary Willis Montgomery (1850-1918), a descendant of

Henry Livingston and Sarah Welles. Evidently misinformed on several counts, M. W. Montgomery professed ignorance of "any direct claim" by Moore to authorship of "A Visit from St. Nicholas." Her conjecture of an original, irretrievably lost printing of "Visit" in the Poughkeepsie

Eagle is impossible, since the

Eagle only

became the Eagle in 1834, and did not exist in any form before 1828. The early newspaper version that Livingston family members recall reading and keeping was most likely the one in the Poughkeepsie

Journal on January 16, 1828.

Found on Newspapers.com The January 16, 1828 text of "A Visit from St Nicholas" in the Poughkeepsie

Journal was reprinted from the

National Gazette. It seems the Poughkeepsie editor had no knowledge of a prior appearance anywhere, let alone in his own newspaper. (And Major Livingston's published newspaper contributions typically were signed, "R.") Nevertheless, the 1914 letter from Mary Willis Montgomery, transcribed below, is an important document for Livingston genealogy and the history of authorship claims for Henry Livingston.

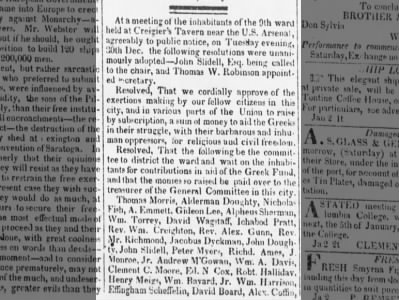

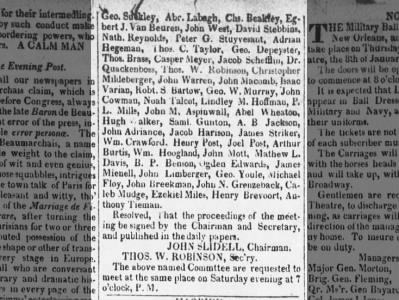

TO THE EDITOR OF THE SUN--Sir: An article in your paper of December 26 in which reference was made to the almost worldwide popularity of the poem entitled "A Visit from St. Nicholas" leads me to ask whether it is true, as I have heard stated, that the Rev. Clement C. Moore never himself made any direct claim to the authorship of this poem, which has been attributed to him.

I ask this because the testimony which points to Major Henry Livingston as being its author appears to be too strong to be ignored, and it might be interesting to sift the evidence. Major Livingston lived near Poughkeepsie, in a house built by his grandfather, Gilbert Livingston, where, it is asserted by his children, he wrote the poem on a Christmas Eve, and read it to them the following morning. I have heard both a daughter and a granddaughter of Major Livingston say that they were present on that occasion and that the success of his poem in the home circle led Major Livingston to consent to its publication in a Poughkeepsie newspaper.

Neither the name of the newspaper nor the exact date of publication was remembered by them, but they were positive that it antedated by several years the publication of the poem in the Troy Sentinel. The original manuscript and a copy of the Poughkeepsie paper containing this first publication of the poem were in the possession of Major Livingston's oldest son for a great many years, but were lost after his death.

A letter in my possession, written by a daughter of Major Livingston in 1879, says: "I well remember our astonishment when we saw it [the poem] claimed as Clement C. Moore's many years after my father's decease, which took place more than fifty years ago. We have often said, 'The style is so exactly his; how would it be possible that another could express the same originality of thought, and use the same phrases, so familiar to us as father's!'"

I have heard it stated by the two ladies I have already referred to, daughter and granddaughter respectively of Major Livingston, and by his youngest son, that there was present as a guest in the house on the Christmas morning when the poem was read a young lady who derived so much pleasure from the reading of it that she requested Major Livingston to give her a copy, which he did. This lady, on leaving Major Livingston's house, went to the house of Mr. Moore, where she had been engaged as governess to his children. The testimony I have outlined is given in perfect good faith by people of the highest character.

How is one to sift the evidence? It would seem as if the only proof would be the date of first publication. Thinking that the newspaper in question might have been the Poughkeepsie Eagle, I applied at their office some years ago for permission to look over their back files of the 1820's, but was told that all had been destroyed in a fire that had burned out the Eagle office.

Major Livingston left a number of poems, all written with a light touch, and most of them in a humorous vein. A few were published in the local papers, but always, I believe, anonymously.

M. W. MONTGOMERY.

New York, January 3.

Mrs. Montgomery's

1914 letter to the editor of the New York

Sun elicited swift answers in the same newspaper. In replies published on

January 7, 1914, two readers cited inscribed copies of

Clement C. Moore's 1844 Poems, which contains "A Visit from St. Nicholas" on pages 124-127, as strong evidence of Moore's characteristically "modest" claim to authorship of the Christmas classic.

John H. Morrison reported that he owned a copy presented "To Dr. Stewart with the respects of the author." A. S. Phelps said he owned a copy inscribed to his father, a student of Dr. Moore's at the General Theological Seminary, "as a token of friendship from the author."

From Philadelphia a few days later, Joseph Jackson wrote to express his wonderment over the very idea of an authorship controversy:

"That there should be any doubt as to Clement C. Moore's authorship of

"A Visit from St. Nicholas" at this late day seems to be

incomprehensible."

Mr. Jackson specifically called attention to the manuscript copy of "Visit" owned by the

New York Historical Society. In view of Clement C. Moore's personality and character, Jackson reasoned that

"Dr. Moore's entire life, which was always quiet, retiring and modest, does not admit of the slightest hint that he purposely or involuntarily assumed the robe of another poet."

In 2008 Christie's handled a

presentation copy of Moore's 1844 Poems inscribed to Nathaniel Paulding "from his old & sincere friend, the author."

Seth Kaller offers an association copy of the 1844 volume inscribed by Clement C. Moore to “Mrs. De Kay with the respects of the author, Mar. 1846.” "Mrs. De Kay" is Janet Drake De Kay, daughter of the celebrated poet Joseph Rodman Drake.

This day Abe Books lists five inscribed copies for sale. One copy to an unidentified recipient is available through

The Fine Books Company.

Bauman Rare Books has one inscribed to "Mr. Miller, / From the author, / Dec. 1849".

Town's End Books has another copy inscribed

"To Miss Southey | with the respects | of the author. | June,

1844." On the verso side of the half title page, the author has also

added a line of correction for page 58.

Glenn Books offers a presentation copy inscribed by Moore to "The Rev. Dr. Barry, with the respects of the

author, Mar. 1846". The longest and perhaps most interesting inscription of all appears in the volume offered by

Argosy Book Store. Moore presented this copy in Newport to a Dr. Raphall. The author's signed note reads

Newport, Sep. 2, 1850

Dear Sir,

I wish I had something to send you, better than this little book. But, such as it is, be pleased to accept it as a mark of respect from one of your much gratified auditors.

Clement C. Moore

Rev. Dr. Raphall --Argosy Book Store via AbeBooks

The Rev. Dr. Raphall can only be

Morris Jacob Raphall who would become "the leading rabbi not only in New York—then the home of a quarter of the nation’s Jews—but in the country," as

Howard B. Rock observes in his September 19, 2012

Tablet essay. As the Civil War began, Dr. Raphall also became famous for his controversial

defense of slavery on biblical grounds.

In 1850, however, Dr. Raphall was embarked on "a public literary career" that first flourished in England, as

Rabbi Henry Vidaver emphasizes in his 1868 memorial:

...very few English speaking Israelites knew the value and greatness of our Hebrew literature, and very few gentiles in England had a sound idea of Jew and Judaism. And at that time Dr. Raphall began to lecture and to write! A Jew lectures in English; in pure and sublime English; in the English of Addison, Hume, and Macaulay. What a marvel! And upon what subjects? Upon Hebrew poetry, upon rabbinical wisdom and literature!

My friends, I am not able to adequately describe the salutary influence his lectures and writings exercised upon Jews and Gentiles, especially in England; the immense good he effected for Israel and his religion….

--"Memorial of Rev. Morris J. Raphall, Ph.D." in The Jewish Messenger, July 3, 1868

Arrived from Birmingham, England in 1849, Dr. Raphall lectured on Hebrew literature in Brooklyn, Philadelphia, Baltimore, Charleston, and Richmond. "It was poetry illustrating poetry" according to the Richmond

Whig notice of March 26, 1850. In August 1850 the

Newport synagogue temporarily reopened for Dr. Raphall's course of six lectures on biblical poetry. Moore the seminary Professor of Hebrew attended one or more lectures, obviously, and pronounced himself one of the eloquent rabbi's many "gratified auditors."

In October 2015 Stewart Ogilby offered for sale the

Ogilby family copy, neatly inscribed in October 1844 "To the Rev. Dr. Ogilby, with the best respects of the author." As described by Stewart Ogilby, this volume contains

"errata corrections made by Moore in this book in his own handwriting."

John David Ogilby (1810-1851) was a younger colleague of Clement C. Moore's at General Theological Seminary from 1841 to 1846. Former seminary student Clarence Augustus Walworth remembered Ogilby as an earnest controversialist, opposed both to "Romanism" and low-church fundamentalism. By contrast, Walworth recalled Clement C. Moore as "unconsciously" eccentric:

Santa Claus himself could not be more welcome to children than was this odd and genial man upon his appearance in the Hebrew class. He was very particular in his ways; but one great feature of his peculiarity was, that he was utterly unartificial. He was droll, but unconsciously so. He never joked in the class, but always something made the classroom seem merry when he was in it. He was a true scholar in Hebrew. His knowledge of Hebrew words did not seem to be derived from the dictionary alone. He knew each word familiarly, and remembered all the different places where it occurred in the Hebrew Bible, and so could prove its significance in one place by the meaning which necessarily attached to it elsewhere. --The Oxford Movement in America

Additional volumes will probably emerge from time to time. For now we have identified ten copies of the 1844

Poems inscribed by Clement C. Moore, some with corrections apparently in his hand.