|

| The Grand Review at Washington Harper's Weekly, June 10, 1865 via The Civil War |

Commentators often quote from the bracketed preface to Battle-Pieces, but rarely do they notice how Melville imagines his collected poems in military terms as soldiers or rather groups of soldiers on parade.

[With few exceptions, the Pieces in this volume originated in an impulse imparted by the fall of Richmond. They were composed without reference to collective arrangement, but, being brought together in review, naturally fall into the order assumed....]One notable exception is Juana Celia Djelal, who recognizes the military metaphor and reads it as Melville's self-presentation of "an enlisted man in the war of wayward winds." --Melville's Antithetical Muse: Reading the Shorter Poems

Sounds good to me, though in his role of self-editor (rather than poet) I'm tempted to rank him higher. Having composed his Civil War poems, Melville then had to organize them for publication. The act of organizing and presenting his verses is compared to a military review in which Melville as commanding officer (Colonel, say, but ultimately General) arranges his men/verses in their proper formations and superintends their marching/publication in front of hopefully an appreciative crowd. Being well-drilled, these figurative men "naturally fall into the order" of squads, platoons, companies, and battalions that General Melville has assigned them in his brigade of a book.

The Official Homepage of the United States Army helpfully diagrams the formal Organization of Units and Commands

For the sake of exercise I extended Melville's basic metaphor thus:

Squad = line of verseFor an improved, more historically accurate model we should consider Civil War Army Organization

Platoon = stanza

Company = single poem

Battalion = section of poems (thematically or structurally related, perhaps)

Brigade, Division, or Corps might aptly represent a book of poems, or multiple books.

and introduce regiments:

The regiment was the basic maneuver unit of the Civil War.(Closer to home, another helpful site is the Minnesota Historical Society's page on Civil War Military Organization ) Regiments (ten companies) usually began with 1,000 men and were led by colonels.

|

| New York Tribune, Monday, May 22, 1865 |

Melville's most immediate frame of reference for thinking of poems as soldiers in ceremonial review would have been the spectacular Grand Review held May 22-23, 1865 in Washington. The Grand Review was much on the poet's mind and specifically inspired "The Muster," as the full title of that poem acknowledges:

The Muster

Suggested by the Two Days' Review at Washington.

(May, 1865.)

Harper's Weekly for June 10, 1865 features suitably grand illustrations of the event, like the one below of Sheridan's Cavalry (minus Sheridan) passing through Pennsylvania Avenue, May 23, 1865.

It could be fun and potentially useful to compile a fuller list or index of Melville's military metaphors. For this project I'm most interested in Melville's use of military terms as figures of speech that signify something else. Such an index I'm guessing would be surprisingly extensive.

For a start, here's a good one from Melville's surviving correspondence. The military metaphor in this letter represents printed letters of the alphabet as soldiers and their weapons. Melville writes from Boston to Evert Duyckinck on February 24, 1849:

|

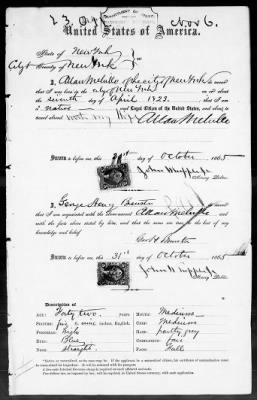

| Image Credit: Brown Digital Repository |

Joyce Sparer Adler's important study of War in Melville's Imagination deals with the theme of war-or-peace. Figurative language and imagery of war receive sustained attention in the chapter on Moby-Dick:

"War imagery characterizes not only the scenes of battle with the whale but all portrayals of ship and crew; of roles and relationships; of goals, machinery, and methods."Cited examples include painted whaling scenes that "remind Ishmael of battle pictures lining the gallery of the triumphal hall at Versailles"; and the metaphor of military ordnance in the "clamped mortar of Ahab's iron soul."

It could be fun and potentially useful to compile a fuller list or index of Melville's military metaphors. For this project I'm most interested in Melville's use of military terms as figures of speech that signify something else. Such an index I'm guessing would be surprisingly extensive.

For a start, here's a good one from Melville's surviving correspondence. The military metaphor in this letter represents printed letters of the alphabet as soldiers and their weapons. Melville writes from Boston to Evert Duyckinck on February 24, 1849:

I have been passing my time very pleasurably here, But chiefly in lounging on a sofa (a la the poet Grey) & reading Shakspeare. It is an edition in glorious great type, every letter whereof is a soldier, & the top of every "t" like a musket barrel.

--Correspondence, Northwestern Univ Press, ed. Lynn Horth

|

| Image Credit: Newberry Digital Exhibitions |

Related post:

- Military tropes in PIERRE

https://melvilliana.blogspot.com/2015/12/military-tropes-in-pierre.html