|

| Youth on the Prow, and Pleasure at the Helm William Etty, Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons |

"How any man, even if in some mad hours of excitement he had written such a book, could read the proof-sheets and not heave the whole mass upon the fire, we cannot conceive."

--Benjamin J. Wallace on Melville's Pierre

| From The Bard: A Pindaric Ode in The Works of Thomas Gray |

"wrote all the book-notices during the ten years of his editorial charge, and forty-one articles on various subjects."For this reviewer, Typee and Omoo exhibit Melville's characteristic "voluptuousness," Mardi his "dreamy scepticism." Nothing about Moby Dick. Among other interesting points here, Rev. Wallace prefers Dickens and Esther Summerson over Melville and Isabel. From The Presbyterian Quarterly Review, Volume 2 (June 1853): 124-155.

The same "foul flowering" that shows itself in society, appears appallingly in literature. Instead of any general review of the books that our sons and daughters read with so much eagerness, we will select the works of one Author—a man of genius, else we should not think it worth our while to notice him—a writer of a most beautiful, not to say delicious style, at least in his earlier productions, a man of sufficient ability to concentrate, and then spread, the miasmata of the country, and so to become an exponent of the disease which is preying upon its vitals. Whom can we mean but Herman Melville? When the foul vapors of the land are pervaded with the light of his brighter genius, or made lurid with the glare of his phosphorescent flashings, they take with tolerable distinctness the form of a voluptuous dreaminess and beauty which first invests all truth with a fair hue, and ends by dissolving it. The pupil in this school is left without fixed principles, or a sure compass; and then by an Epicurean process as old as the world, but never more dangerously realized than now, his leading propensities, carried out without restraint, become the chief good. If we be the victims of a dark fate, if with the semblance of free will, man vainly struggles in a net-work of influences utterly beyond his power to unmesh; if it be doubtful whether God or the devil govern the universe, or whether they exist at all; or if potentially, both are in man, the angelic in the shape of aesthetic beauty, and the demoniac in the shape of pain and low spirits, and so that which theologians call God be simply the aggregate of joy, and love, and beauty, rosy wine and rosy sunsets, and that called devil be only poverty and old age, and icy cold, heartlessness and contempt, hatred and sorrow; if the ministry are a body of cunning men who have taken advantage of a weakness in humanity to climb to place and wealth; if the Church is a vast conventional worldly machine which rebukes only the vice which is not respectable, and winks hard at sin amongst vestrymen, ruling elders, and bank directors; then there is nothing better, muses the young neophyte, than that I should launch my bark,Multiple volumes with the "Young America" article are also accessible courtesy of HathiTrust Digital Library:

Youth at the prow, and pleasure at the helm.He does it. He meets many disciples of the same school, of both sexes, and the revellings described in Putnam's Magazine [in Our Best Society by George William Curtis, February 1853 issue with Fitz-James O'Brien's article, Our Young Authors — Melville] are the result, as natural and legitimate as the flow of water down hill, or the upheaving of the tides beneath the influence of a summer moon. This is the ultimate efflorescence of the choice mingling of voluptuousness and dreamy scepticism.

[Thomas Gray, The Bard: A Pindaric Ode 2.2; earlier verse at 1.3 personifies "huge Plinlimmon" with "his cloud-topt head"]

That we are doing no injustice in speaking of the tendency of these books, we shall attempt to prove by a slight analysis. It pains us to speak evil of any thing. We never do so, except of the works of one who voluntarily appears before the public, and so loses his right of privacy, as an author. That we distinguish between the author and the man appears in this, that we charge on Mr. Melville no intention of evil. For aught we know, he may write purely for amusement, or money, or fame. But the tendency of his writings is public property. Of that only we mean to speak.

"Typee," in point of descriptive power and beauty of style reminds us both of Defoe and Washington Irving. The impression produced by it as a work of genius was both natural and deserved. With Irving, Willis and Curtis, Melville has shown a peculiar power, hitherto supposed to be like picturesque ruins, or very refined manners, only possible in an old country, aristocratic in its institutions. Many ideas of this kind, however, are destined to be exploded by our Western republic. In this beautifully written book, the character of Fayaway has been admired by men and women as its chief gem. Lady writers of high reputation have recorded their admiration in permanently printed words. Yet if the book is truthful, the hero lived in careless ease among these poor Polynesians, without any one effort to benefit them, and both the descriptions and the story of the beautiful central figure imply—shall we use a soft word ?—voluptuousness. This ought to have given the alarm on the threshhold of Mr. Melville's authorship.

"Omoo" advanced another step, not, we presume, in any deliberate design to do mischief, but certainly in the wrong direction. Not content, to say the least, with carelessness as to the welfare of the simple beings amongst whom his hero is represented as amusing himself, in Omoo a deliberate effort is made to hold up to contempt the men and women, who at great cost of labor and sorrow, went to those islands to Christianize and civilize their degraded fellow-men. If these arrows have fallen harmless at their feet, it is not Mr. Melville's fault. If America received the attempt with disgust, it was because America is sagacious, and can appreciate enterprise and virtue. It is too late to sneer at Christian missionaries.

Mr. Melville presently gave us "Mardi." This strange book, it is true is so fashioned, that the author may very readily say that ho had no intention to teach any thing whatever. It professes to be a rhapsody. It sets out to be a South Sea romance; a floating amid sunny and stormy waves, water-lilies and plantains, beautiful women and orientally philosophic and poetic men, kings and courtiers, maidens and attendants, after a peculiar South Sea fashion. But the book has genius, and will be read, and therefore we have something to do with it. It is our business to analyze subtle potions, because we are physicians of the soul. We have said that these books are pervaded with two essences, ever mingling, voluptuousness and dreamy scepticism. By scepticism, we do not mean infidelity, technically so called, or opposition to the Christian religion, but doubt as to almost every thing. In Typee and Omoo, the former element predominates; in Mardi, as is natural, the latter appears more prominently. We have a king, or powerful ruling practical man, a philosopher, who has examined all manner of systems of belief and thought, a poet rich in genius and melody, a mystic maiden whom they ever pursue, who may possibly represent "truth" or "happiness." They voyage the world around, in their Polynesian way, examine all climes, and discuss all methods of existence, find savage and civilized much the same in essence, and end the search as unsatisfactorily as they began. They are amused; their intellect, imagination and sensibilities are played upon by the way; but the result is nought—Pyrrhonism, like the old Greek, or "Nothing," like that celebrated Japanese school of philosophy, of which we read, in which the professors discoursed so eloquently of this ultimate outcrop of human things, that their disciples would cry out for hours, like the Ephesians of Diana, "great is nothing!" "nothing! nothing!" If all this of "Mardi" had been written, mutatis mutandis, in Greece, before the Christian era, we might admire it, and amuse ourselves with it, while lamenting that over such a mind the true light had not risen. But the case is widely different when "the times of this ignorance" have passed away. There is no kind of excuse for dwelling in darkness or penumbra when God hath spoken, and the man that weaves a frail artificial summer-house of leaves and flowers over and around him, that in his twilight arbor he may not see things clearly, but dream amid sensuous enjoyment and skeptical doubt, will presently learn with all like-minded, that it is not with them in responsibility, as with those who moved in procession in Cyprus and at Corinth, where genius and pleasure wove their wreaths around youth and beauty, and gods and demi-gods smiled from heaven and on earth, to their fancy, over their voluptuousness. The true light now shineth, into the noonday must men come with their principles and deeds, or presently God will bring them into a brighter light than the sun at noonday, before men and angels!

If Mr. Melville agrees with us in these statements, and Mardi was written to teach some such lesson, then we have but to inquire the meaning, last of all, of a book called "Pierre, or the Ambiguities." How any man, even if in some mad hours of excitement he had written such a book, could read the proof-sheets and not heave the whole mass upon the fire, we cannot conceive. We will give the reader an idea of it, by tracing the plot in the simplest possible language. A young man is born and brought up in a village where his ancestors had lived and owned a large part of the soil for generations. He is handsome, physically brave, cultivated, an only child, left with his mother, who is a widow, but proud and beautiful. He becomes engaged to a lovely girl, who is devoted to him. He suddenly discovers that his father had an illegitimate child, who exists in the shape of a young lady of remarkable beauty. He determines to protect her, and in order to do so, persuades her to pass for his wife. His mother disowns him, and dies soon after, leaving the entire estate, which was her's by will of the father, to his cousin. The hero flies the village, and presently passes through a number of romantic phases, into incest with his sister. His betrothed bride, who had been on the verge of death at his desertion, now insists on coming to live with him, of course without being married to him, and against the wish of all her relatives. The end of it is, that he murders his cousin, he and his sister commit suicide, and the betrothed bride falls dead at his feet—all before he is of age.

We would inquire whether it is at all necessary to import Parisian novels, in order that we might have the French school full fledged among us, if such books as Pierre are to be tolerated as American literature?

If it be asked whether we charge the author with approving the conduct of his hero, and of any other character in Pierre, (for nearly every one is vicious or silly,) we reply, of course, in the negative. But there is in man a strange passion of sympathy and imitation. The constant familiarity with murder, produces murder; sensuality begets sensuality; a nightmare literature is both cause and effect of a vicious state of society. God creates the beautiful and pure in nature, he establishes it in his kingdom of grace, He "sets the solitary" in no unnatural and horrible position, but in "families." And such influences carried out benignantly, create a pure and virtuous society. With all his faults compare Dickens with Melville, the death of poor Jo with the death of Pierre, Esther Summerson with Isabel. The one* is the breath of morning driving away the pestilence that walketh in darkness, the other the enervating south wind relaxing our vigor, or the hot simoom of the desert, withering the nerves and turning life itself bitter within us. Mr. Melville is a young man. Let him listen to the friendly voices which urge him to a better path.

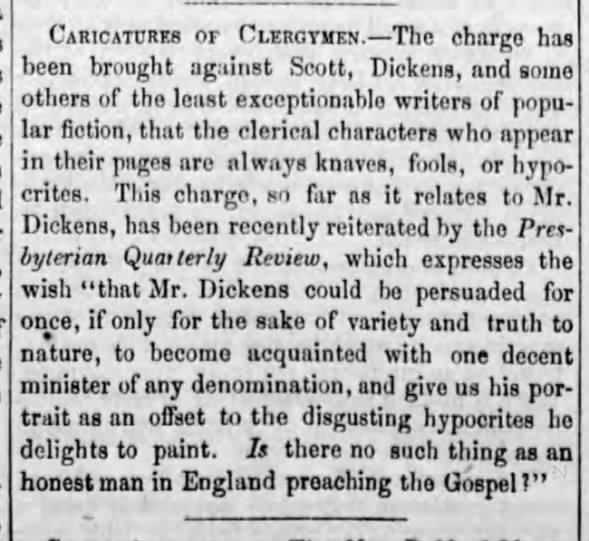

* We wish Mr. Dickens could be persuaded for once, if only for the sake of variety and truth to nature, to become acquainted with one decent minister of any denomination, and give us his portrait as an offset to the disgusting hypocrites he delights to paint. Is there no such thing as an honest man in England preaching the Gospel?

- The Presbyterian quarterly review. v.2 - University of Wisconsin

https://babel.hathitrust.org/cgi/pt?id=wu.89077096881;view=2up;seq=134 - The Presbyterian quarterly review. v.2 1853/54 - Cornell University

https://hdl.handle.net/2027/coo.31924057538807?urlappend=%3Bseq=136 - The Presbyterian quarterly review. v.2 1853/54 - Penn State

https://hdl.handle.net/2027/pst.000060122766?urlappend=%3Bseq=134 - The Presbyterian quarterly review. v.2 1853/1854 Jun-Mar. - University of Michigan

https://hdl.handle.net/2027/mdp.39015074643373?urlappend=%3Bseq=134

|

| Digitized by Google - Original from Cornell University via HathiTrust Digital Library |

|

| Cleveland Plain Dealer - June 22, 1853 via GenealogyBank |

Sat, Jul 2, 1853 – 2 · New England Farmer (Boston, Massachusetts, United States of America) · Newspapers.com

Sat, Jul 2, 1853 – 2 · New England Farmer (Boston, Massachusetts, United States of America) · Newspapers.com

Extracts on Pierre from the 1853 Presbyterian Quarterly Review essay did make their way into the "Our Weekly Gossip" section in Joseph M. Church's Bizarre: for Fireside and Wayside (June 18, 1853), pages 155-6. Introduced there with a fresh hit at Melville's latest book as "the abomination of all abominations, in the shape of romance."

— The last number of the Presbyterian Review has an article entitled "Young America," from which we select the following touching Melville's last work—the abomination of all abominations, in the shape of romance—entitled "Pierre or the Ambiguities:" ...

<https://hdl.handle.net/2027/nyp.33433081750360?urlappend=%3Bseq=168>

Herman Melville: The Contemporary Reviews, edited by Brian Higgins and Hershel Parker (Cambridge University Press, 1995; paperback 2009) has the earlier notice of Pierre ("wild, wayward, overstrained in thought and sentiment, and most unhealthy in spirit"), as first published in Church's Bizarre: for Fireside and Wayside on August 21, 1852.

No comments:

Post a Comment