|

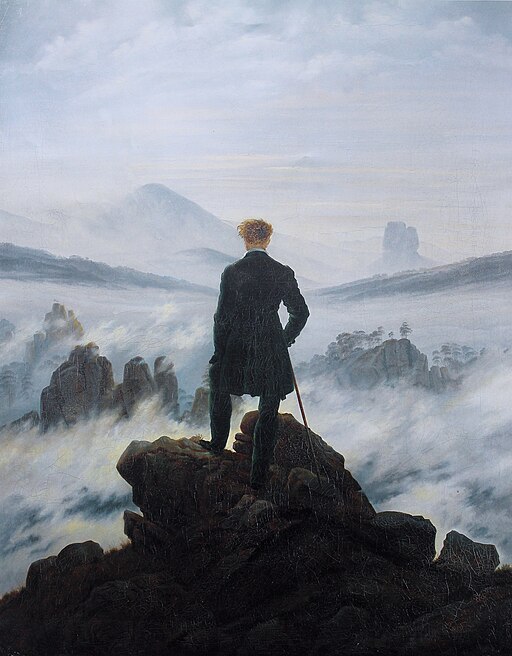

| The wanderer above the sea of fog Caspar David Friedrich via Wikimedia Commons |

In Herman Melville: Making of the Poet (Northwestern University Press, 2008) Hershel Parker observes the evolution of Melville's seventh book in "Wordsworthian" passages that demonstrate "the unfolding of the inner mind in majestic natural settings" (94). One specific influence on Pierre; Or, The Ambiguities (1852) is a passage from Wordsworth's Excursion (book 3) giving names to rocks, a source for sections in Pierre about boulders named Memnon and Enceladus as shown in Herman Melville: A Biography Volume 2, 1851-1891 pages 57-58. Another source from The Excursion, book 5, is cited by Thomas F. Heffernan: the "fertilising moisture" of certain rocks is recast in Pierre; Or, The Ambiguities as "a subtile moisture, which fed with greenness" the nearby ground ("Melville and Wordsworth," American Literature, November 1977: 338-351 at 340 fn 9.).

The following passage from Wordsworth's "Descriptive Sketches" refers to "nearer mist," an unusual phrasing which also occurs in Pierre, in a similar context:

— 'Tis morn: with gold the verdant mountain glows,More high, the snowy peaks with hues of rose.Far stretched beneath the many-tinted hillsA mighty waste of mist the valley fills,A solemn sea! whose vales and mountains roundStand motionless, to awful silence bound.A gulf of gloomy blue, that opens wideAnd bottomless, divides the midway tide.Like leaning masts of stranded ships appearThe pines that near the coast their summits rear;Of cabins, woods, and lawns a pleasant shoreBounds calm and clear the chaos still and hoar;Loud thro' that midway gulf ascending, soundUnnumber'd streams with hollow roar profound:Mount thro' the nearer mist the chaunt of birds,

And talking voices, and the low of herds,The bark of dogs, the drowsy tinkling bell,And wild-wood mountain lutes of saddest swell.

-- Descriptive Sketches, Poetical Works page 50

And below, the passage with "nearer mist" extracted from the online text of Pierre at Project Gutenberg:

Well for Pierre it was, that the penciling presentiments of his mind concerning Lucy as quickly erased as painted their tormenting images. Standing half-befogged upon the mountain of his Fate, all that part of the wide panorama was wrapped in clouds to him; but anon those concealings slid aside, or rather, a quick rent was made in them; disclosing far below, half-vailed in the lower mist, the winding tranquil vale and stream of Lucy's previous happy life; through the swift cloud-rent he caught one glimpse of her expectant and angelic face peeping from the honey-suckled window of her cottage; and the next instant the stormy pinions of the clouds locked themselves over it again; and all was hidden as before; and all went confused in whirling rack and vapor as before. Only by unconscious inspiration, caught from the agencies invisible to man, had he been enabled to write that first obscurely announcing note to Lucy; wherein the collectedness, and the mildness, and the calmness, were but the natural though insidious precursors of the stunning bolts on bolts to follow.

But, while thus, for the most part wrapped from his consciousness and vision, still, the condition of his Lucy, as so deeply affected now, was still more and more disentangling and defining itself from out its nearer mist, and even beneath the general upper fog. For when unfathomably stirred, the subtler elements of man do not always reveal themselves in the concocting act; but, as with all other potencies, show themselves chiefly in their ultimate resolvings and results. Strange wild work, and awfully symmetrical and reciprocal, was that now going on within the self-apparently chaotic breast of Pierre. As in his own conscious determinations, the mournful Isabel was being snatched from her captivity of world-wide abandonment; so, deeper down in the more secret chambers of his unsuspecting soul, the smiling Lucy, now as dead and ashy pale, was being bound a ransom for Isabel's salvation. Eye for eye, and tooth for tooth. Eternally inexorable and unconcerned is Fate, a mere heartless trader in men's joys and woes.

I was prompted to wrestle again with Melville's words in book 5 of Pierre while reading in Hershel Parker's new book, Melville Biography: An Inside Narrative. In chapter 2, "Textual Editor as Biographer in Training" (35-36), Parker explains the practically irresistible emendation of "nearer" to "nether." Parker offers this appealing change, now effected I see at pages 105 in the Trade Paper edition of Pierre or The Ambiguities (3rd printing, Northwestern University Press, 1999), as an example of the common readerly response of mentally, then marginally correcting a text by substituting "the right word" for a wrong one. The correction makes good "topographical" sense, neatly clarifying the upper vs lower distinction that is already there, an ongoing contrast that later on includes the explicit reference to "upper and nether firmaments." Earlier on Melville pictured "the lower mist" hiding Lucy-as-valley from Pierre-as-mountaineer. Well then, nether means "lower" so correcting "nearer mist" to "nether mist" eliminates the puzzling "nearer" and keeps everything and everybody properly aligned and oriented.

Piece of cake?

Maybe not, after all, considering the precedent in Wordsworth--and considering, too, the shared situation of a youthful traveler in the mountains: Wordsworth's literal Alps and valley, Melville's metaphorical mountain and valley. Metaphorically, Melville's upper and lower somehow represent parts of the psyche, conscious and repressed unconscious. But here as throughout Pierre the language is tricky, the progress convoluted.

Two paragraphs are involved, and looking again and trying to follow more closely I see a possible twist in the second paragraph, a turn involving both action and orientation that is signaled at the start of the paragraph in the word "But." Before, in the first paragraph, we were looking down into the valley with Pierre seeing things as they looked "to him," but here, wait: has the orientation weirdly shifted? The grammatical subject of the relevant sentence is an abstract noun, condition--more concretely, Lucy's condition. What is emerging more visibly? Lucy's condition. From what is Lucy's condition "disentangling and defining itself? From, emerging out from, its "nearer mist."

ITS. Possessive pronoun, third person, antecedent "the condition of Lucy." Nearer to whom I guess is still the question. Most immediately to Lucy, below, still contrasted with Pierre above, in or closer to the "upper fog." It is the same "lower mist" as in the previous paragraph, only pictured now as nearer, closer to Lucy. Yes all of this has reference to the mind of Pierre, his conscious thoughts and unconscious stirrings. These metaphorical mists that lately had hidden Lucy from Pierre's conscious thoughts are both "nether" and "nearer": "nether" to Pierre on the mountain, "nearer" to Lucy in the valley. Lucy's condition is emerging from the mists nearer to, closer to Lucy's condition, which are also nether, lower mists in Pierre's subconscious mind.

What is Lucy's figurative condition? That of a cruelly suffering crime victim, tied up in the basement and held for ransom. O!

In Wordsworth's scene a sea of mist covers the valley below, seen through an opening or "gulf" in the mist. Bordering this figurative bay is a figurative "shore" of familiar things, all comfortably natural: cabins, woods, lawns. Melville's Lucy belongs to the same kind of cozy valley scenery, seen like the features of Wordsworth's "pleasant shore" through a hole in the mists. In Wordsworth's passage, bird songs and other sounds from that homey lower world waft up through "nearer mist." That's the mist closer to the birds, people, cows and dogs.

I think. Hmm. I have to admit what Wordsworth means by his "nearer mist" is for me hard to de-mistify. And what about other (later?) versions with many changes including the change of "nearer mist" to "nearer vapours"?

"for Wordsworth, the nearer, domestic" sounds are distinct, as in Clarke, "but not those heard through the gloomy midway gulf."

-- "The Image of a Mighty Mind (1805, Book 13)" in William Wordsworth's The Prelude: A Casebook, edited by Stephen Gill (Oxford University Press, 2006) page 229. Update! now accessible online via Oxford Academic:Wordsworth, Jonathan, 'The Image of a Mighty Mind (1805, Book 13)', in Stephen Gill (ed.), William Wordsworth’s: The Prelude (New York, NY, 2006; online edn, Oxford Academic, 31 Oct. 2023), https://doi.org/10.1093/oso/9780195180916.003.0008.

I need to get hold of these studies, too:

- Maxine Moore, "Melville's Pierre and Wordsworth: Intimations of Immorality." Ha! immorality. New Letters 39 (Summer 1973): 89-107; and

- Michael Davitt Bell, "The Glendinning Heritage: Melville's Literary Borrowings in Pierre." Studies in Romanticism 12 (Fall 1973): 741-762; and

- Hershel Parker, “Melville and the Berkshires: Emotion-Laden Terrain, ‘Reckless Sky-Assaulting Mood,’ and Encroaching Wordsworthianism,” in American Literature: The New England Heritage, ed. James Nagel and Richard Astro (New York: Garland Publishing, 1981) 65-80; and

- Johnathan Hall, "The Non-correspondent Breeze: Melville's Re-writing of Wordsworth in Pierre." ESQ: A Journal of the American Renaissance 39 (1993): 1-19.

Update

Hey look! a whole dissertation by Cory R. Goehring on

"The Wordsworthian Inheritance of Melville's Poetics."

And check this out, Robert A Duggan, Jr. on Melville's poem "The House-top" and The Prelude.

It's great to see the Wordsworth-gap closing, as identified by R. D. Madison:

"The study of the relationship between Melville and Wordsworth remains one of the largest gaps in Melville criticism."

-- "Literature of Exploration and the Sea" in A Companion to Herman Melville (Wiley-Blackwell, 2006; paperback 2015) edited by Wyn Kelley, page 285.

No comments:

Post a Comment