|

| A Visit from Saint Nicholas. New York: James G. Gregory, 1862 via Library of Congress <www.loc.gov/item/24005582/>. |

|

| Daily National Intelligencer - January 2, 1826 via GenealogyBank |

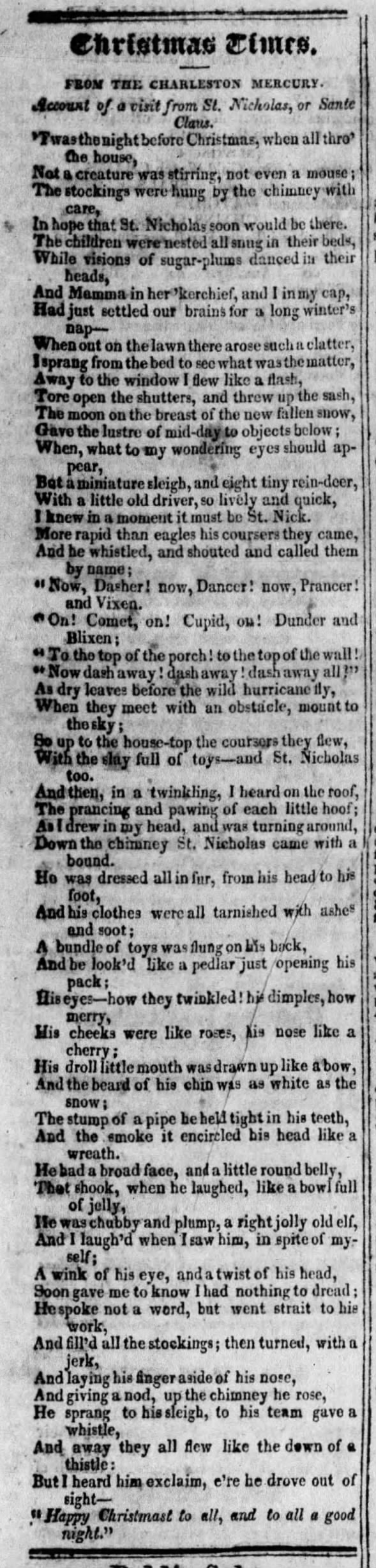

CHRISTMAS TIMES.

FROM THE CHARLESTON MERCURY.

Account of a visit from St. Nicholas, or Sante Claus.

’Twas the night before Christmas, when all thro’ the house,Some distinctive features of 1826-7 newspaper reprintings "from the Charleston Mercury," not present in the Troy Sentinel first printing:

Not a creature was stirring, not even a mouse;

The stockings were hung by the chimney with care,

In hope that St. Nicholas soon would be there.

The children were nested all snug in their beds,

While visions of sugar-plums danced in their heads,

And Mamma in her ’kerchief, and I in my cap,

Had just settled our brains for a long winter’s nap —

When out on the lawn there arose such a clatter,

I sprang from the bed to see what was the matter.

Away to the window I flew like a flash,

Tore open the shutters, and threw up the sash.

The moon on the breast of the new fallen snow,

Gave the lustre of mid-day to objects below;

When, what to my wondering eyes should appear,

But a miniature sleigh, and eight tiny rein-deer,

With a little old driver, so lively and quick,

I knew in a moment it must be St. Nick.

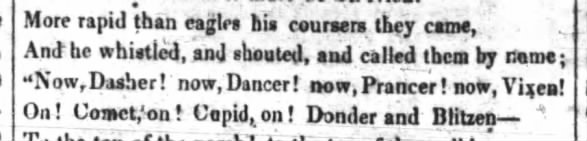

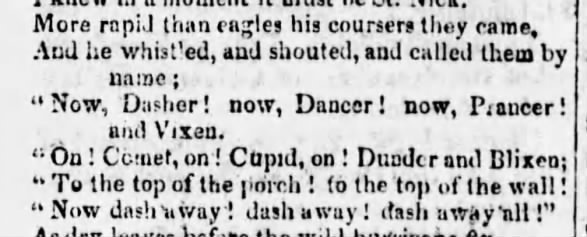

More rapid than eagles his coursers they came,

And he whistled, and shouted, and called them by name;

“Now, Dasher! now, Dancer! now, Prancer! and Vixen.

“On! Comet, on! Cupid, on! Dunder and Blixen;

“To the top of the porch! to the top of the wall!

“Now dash away! dash away! dash away all!”

As dry leaves before the wild hurricane fly,

When they meet with an obstacle, mount to the sky;

So up to the house-top the coursers they flew,

With the sleigh full of Toys—and St. Nicholas too.

And then, in a twinkling, I heard on the roof,

The prancing and pawing of each little hoof;

As I drew in my head, and was turning around,

Down the chimney St. Nicholas came with a bound.

He was dressed all in fur, from his head to his foot,

And his clothes were all tarnished with ashes and soot;

A bundle of toys was flung on his back,

And he look’d like a pedlar just opening his pack;

His eyes—how they twinkled! his dimples, how merry,

His cheeks were like roses, his nose like a cherry;

His droll little mouth was drawn up like a bow,

And the beard of his chin was as white as the snow;

The stump of a pipe he held tight in his teeth,

And the smoke it encircled his head like a wreath.

He had a broad face, and a little round belly,

That shook, when he laughed, like a bowl full of jelly.

He was chubby and plump, a right jolly old elf,

And I laugh'd when I saw him, in spite of myself;

A wink of his eye, and a twist of his head,

Soon gave me to know I had nothing to dread;

He spoke not a word, but went straight to his work,

And fill’d all the stockings; then turned, with a jerk,

And laying his finger aside of his nose,

And giving a nod, up the chimney he rose.

He sprang to his sleigh, to his team gave a whistle,

And away they all flew like the down of a thistle:

But I heard him exclaim, ere he drove out of sight—

"Happy Christmas to all, and to all a good night."

- Singular "hope" in line 4 instead of "hopes."

- Children "nested" not "nestled" in line 5.

- Reindeer names Dunder and "Blixen" not "Blixem"

- Re-ordering of exclamation marks and commas around first three reindeer names, for example "Now, Dasher!" instead of "Now! Dasher, now!"

|

| A Visit from St. Nicholas. Boston: L. Prang & Co., 1864 via Library of Congress, <www.loc.gov/item/73169323/>. |

"It was not until the Sentinel broadsheet of 1830 that the exclamation marks and commas were transposed, to read "Now, Dasher!" --Chapter 3, Who Wrote The Night Before Christmas, (McFarland & Company, 2016) page 18; see also page 23.The revision to "Now, Dasher!" is not an original feature of the holiday poem as published in 1830 by the Troy Sentinel. Nevertheless, as Jackson correctly states, the 1830 Troy Sentinel broadside did make significant changes to the usual punctuation including exclamation marks in the next line of reindeer names. With revised punctuation the new and metrically improved line in 1830 reads, "On, Comet! On, Cupid! On, Dunder and Blixem!" After further investigation, however, I'm finding that these 1830 revisions in the second line of reindeer names had almost no direct influence on subsequent reprintings. Newspapers long continued to favor the weirdly punctuated second line of reindeer names as exemplified in the first printing:

On! Comet, on! Cupid, on! Dunder [or Donder] and Blixem [or Blixen, or Bltizen]So did many books, including the landmark New-York Book of Poetry with text presumably authorized by Clement C. Moore himself.

| The New-York Book of Poetry (New York, 1844) page 218 |

Despite the availability of Moore's best text after 1844, the odd punctuation around Comet and Cupid, Dunder and Blixem persisted for decades in published anthologies.

| The Poets and Poetry of America Ed. Rufus W. Griswold (Philadelphia, 1858) |

'Now, Dasher! now, Dancer! now, Prancer! now, Vixen!It's Dunder not Donder in The Young Speaker (New Haven, 1845), but editor John E. Lovell still gives the improved punctuation in the second line of reindeer names.

On, Comet! on, Cupid! on, Donder and Blixen!

|

| Marked passage in "Christmas Times" by "Moore" (Lesson 151) in The Young Speaker, ed. John E. Lovell (New Haven, 1845) page 200 |

Hop, and Mop, and Drap so clear,

Pip, and Trip, and Skip, that were

To Mab their sovereign dear,

Her special maids of honour;

Fib, and Tib, and Pinck, and Pin,

Tick, and Quick, and Jill, and Jin,

Tit, and Nit, and Wap, and Win,

The train that wait upon her.

--Michael Drayton, Nymphidia. The History of Queen Mab; or, The Court of Fairy

Wed, Dec 24, 1845 – Page 2 · Wilmington Chronicle (Wilmington, North Carolina) · Newspapers.com

Wed, Dec 24, 1845 – Page 2 · Wilmington Chronicle (Wilmington, North Carolina) · Newspapers.comWhy then did so many newspaper editors, and apparently even Moore himself in 1837, fail to fix the punctuation in the second line of reindeer names? I blame Dunder and Blixem. Not the reindeer, but their resonant names, in all their varying forms, as triggers of a stereotype with comical and also potentially offensive associations in the 19th century. Moore's St. Nicholas is mainly "Dutch" by association: with the pseudo-Dutch heritage invented by Washington Irving in the guise of Diedrich Knickerbocker; and according to T. W. C. Moore, by mental association with a "portly rubicund Dutchman" living near the poet's family home in Chelsea. Readers with real Dutch ancestry might justly protest with Irving's friend (and Clement C. Moore's seminary colleague) Gulian Crommelin Verplanck that Americans had "imbibed much of the English habit of arrogance and injustice towards the Dutch character.” In Verplanck's view, Irving's "burlesque History of New York" betrayed a talented mind

"wasting the riches of its fancy on an ungrateful theme, and its exuberant humour in a coarse caricature" --Quoted by Derek Kane O’Leary, Journal of the History of Ideas blog, Dutch Pasts and the American Archive.Fans or haters, readers of A History of New-York would have been well-prepared for caricature. They already knew that St. Nicholas smoked like a chimney and had been witnessed "laying his finger beside his nose" before flying away "over the treetops" in his aerial wagon. Elsewhere in his influential History, Irving also quoted the oath supposedly characteristic of Dutchmen, "Dunder and blixum!" Moore's St. Nick whistles, shouts, and calls the roll of reindeer names. By the time he gets to Dunder and Blixem, he could be swearing at the lot.

Below, another reprinting "FROM THE CHARLESTON MERCURY" headed "Christmas Times," this one in the Lexington, Kentucky Reporter of January 23, 1826:

Mon, Jan 23, 1826 – 4 · Kentucky Reporter (Lexington, Kentucky) · Newspapers.com

Mon, Jan 23, 1826 – 4 · Kentucky Reporter (Lexington, Kentucky) · Newspapers.com

Additional reprintings "From the Charleston Mercury," all with the variant forms "nested"; "Blixen"; and "Now, Dasher!"

- Frankfort, Kentucky Commentator, January 28, 1826

- Leesburg, Virginia Genius of Liberty, December 26, 1826

- Poultney, Vermont Northern Spectator, December 27, 1826

Wed, Dec 27, 1826 – 1 · Northern Spectator (Poultney, Vermont) · Newspapers.com

Wed, Dec 27, 1826 – 1 · Northern Spectator (Poultney, Vermont) · Newspapers.com- Poulson's American Daily Advertiser (Philadelphia, PA) December 24, 1828 [Headed "Christmas Times," without crediting the Charleston Mercury or any source.]

Related posts:

- Montreal Visit from St Nicholas, 1826

https://melvilliana.blogspot.com/2021/11/montreal-visit-from-st-nicholas-1826.html

- Charleston Mercury, early printings of A Visit from St Nicholas

https://melvilliana.blogspot.com/2019/12/charleston-mercury-early-printings-of.html

- Genius of Liberty, 1826 reprinting of A Visit from St Nicholas

https://melvilliana.blogspot.com/2019/12/genius-of-liberty-1826-reprinting-of.html

- First printing of A Visit from St Nicholas

https://melvilliana.blogspot.com/2019/04/first-printing-of-visit-from-st-nicholas.html

- Dunder-Donder, Blixem-Blixen, Dunder Mifflin, Donder and Blitzen

http://melvilliana.blogspot.com/2017/03/dunder-donder-blixem-blixen-dunder.html

- Pre-1844 attributions to Clement C. Moore

https://melvilliana.blogspot.com/2018/08/pre-1844-attributions-of-visit-from-st.html

No comments:

Post a Comment