Here's a sample of my latest effort on Substack, documenting formerly unrecognized literary debts to some version of E. C. Brewer's pop-science guidebook in another 1854 short fiction by Herman Melville, Poor Man's Pudding and Rich Man's Crumbs. The borrowings identified so far all occur in "Poor Man's Pudding," the first of these paired sketches. Evidently Melville, having successfully ventriloquized Dr. Brewer on familiar science in "Poor Man's Pudding," kept his guidebook handy for the more extensive series of creative appropriations just uncovered in The Lightning-Rod Man.

As shown below, a closer look at the mechanics of Melville's rewriting reveals his penchant for parallelism. Further investigation, of the sort I hope to continue on Substack, may reveal other instances where Melville forges new parallel structures from the raw material of a source-text.

Near the close of “Poor Man’s Pudding,” the narrator records his observation of the oppressively “damp” and “heavy” air in the Coulters’ home, and then generalizes about the badly ventilated rooms that poor people too often inhabit, especially in winter. Invoking some imaginary abuser (maybe Malthus) of the poor and their alleged “instinct” for “ill-ventilation,” Melville’s narrator protests in their defense that stale indoor air has one great advantage “to any shiverer” in being warmer than air circulated and cooled through ventilation.

This ill-ventilation in winter of the rooms of the poor—a thing, too, so stubbornly persisted in—is usually charged upon them as their disgraceful neglect of the most simple means to health. But the instinct of the poor is wiser than we think. The air which ventilates, likewise cools. And to any shiverer, ill-ventilated warmth is better than well-ventilated cold.

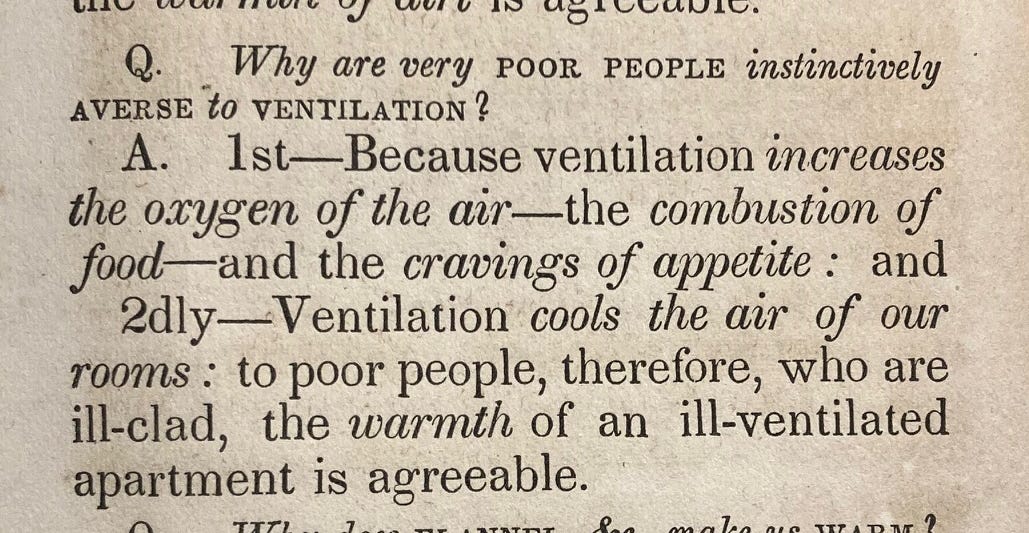

Rather than evincing habitual neglect of good health, as ostensibly alleged by unnamed critics, the observed preference for bad ventilation in winter results from the natural human “instinct” to keep warm. Thus reasons Melville’s compassionate narrator, who takes his theme directly from Dr. Brewer’s section on “Animal Heat,” #1115 in Peterson’s Familiar Science. Image below reproduces the same Q-and-A as it appears on page 93 of A Guide to the Scientific Knowledge of Things Familiar (New York: C. S. Francis & Co. and Boston: Crosby, Nichols & Co., 1854).

Q. Why are very POOR PEOPLE instinctively AVERSE to VENTILATION ?

A. 1st–Because ventilation increases the oxygen of the air—the combustion of food and the cravings of appetite : and

2dly—Ventilation cools the air of our rooms : to poor people, therefore, who are ill-clad, the warmth of an ill-ventilated apartment is agreeable.

In paraphrasing his source-text near the end of “Poor Man’s Pudding,” Melville has disregarded the first part of Dr. Brewer’s answer. Instead of bothering about scientific processes of oxygenation and combustion, Melville keys on the second part, about ventilation. As the latter part of the answer in Familiar Science #1115 explains, “poor people” without adequate clothing to wear actually prefer rooms without good air circulation for their relative warmth, in contrast to rooms that are better ventilated and therefore colder.

FAMILIAR SCIENCE #1115

Ventilation cools the air of our rooms :

MELVILLE

The air which ventilates, likewise cools.

Melville’s rewrite turns Brewer’s word ventilation into a verb, making the grammar of “ventilates” parallel to that of “cools.” Both the original and Melville’s rewrite have the word cools in italics.

The rest of the paraphrase features another parallelism created through revision of Melville’s source-text. Melville copied “ill-ventilated” from his source in Brewer’s Guide page 93 or Familiar Science #1115, and added “well-ventilated” to yield contrasting, parallel descriptors. He strengthened the parallelism through antithesis by copying the noun “warmth” and adding “cold” to sharpen the contrast in fresh, perfectly parallel phrases: “ill-ventilated warmth” vs. “well-ventilated cold.”

FAMILIAR SCIENCE #1115

… to poor people, therefore, who are ill-clad, the warmth of an ill-ventilated apartment is agreeable.

MELVILLE

And to any shiverer, ill-ventilated warmth is better than well-ventilated cold.

Another addition is the figure of “any shiverer,” one of the best changes Melville made to his source-text in some version of Dr. Brewer’s handy guidebook of popular science. When creatively rewriting source material, Melville often gravitates to the concrete and personal. In this case, where his source generalized about the predicament of “ill-clad” poor people. Melville individualizes the point of view, changing the perspective from that of “poor people” in the abstract to that of “any shiverer.” At the same, the construction invites empathy by appealing to a relatable experience of common humanity. In the image of “any shiverer,” Melville has visualized how any person, not excluding any reader, might feel and act in a cold apartment, with no winter clothes.

Related posts:

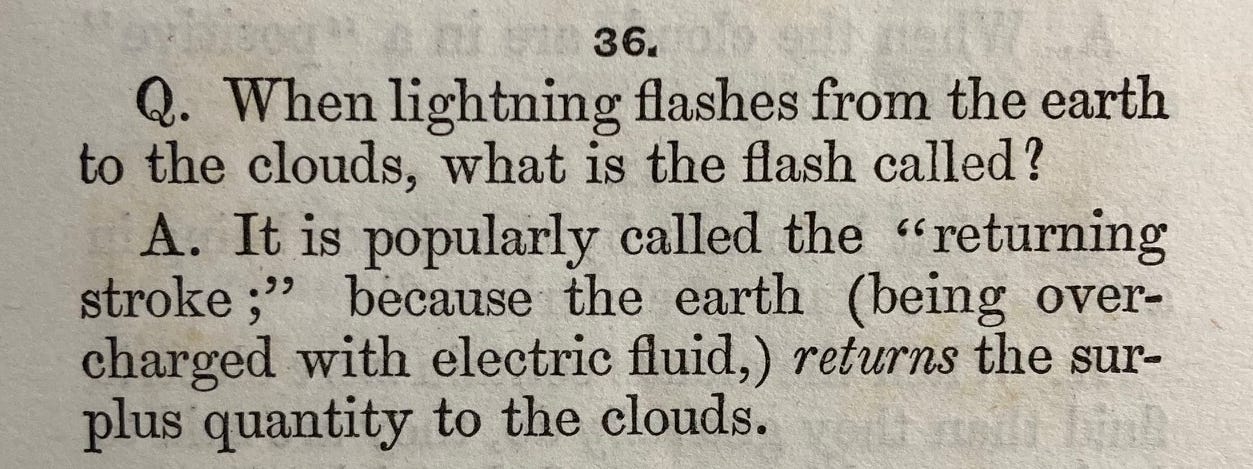

- Too-familiar science in The Lightning-Rod man

https://melvilliana.blogspot.com/2022/03/too-familiar-science-in-lightning-rod.html - Come away from the wall

https://melvilliana.blogspot.com/2022/03/come-away-from-wall.html