|

| Thomas Ritchie, Jr. via Find A Grave |

Previous research has largely, though by no means exclusively, focused on archives from New York, Boston, and the northeastern United States. Relatively neglected southern and western newspapers and periodicals, and foreign publications as well, in print and online archives, seem especially likely to yield important discoveries in the future. --Leviathan 13.1, March 2011Now that Genealogy Bank has old issues of Virginia newspapers in their database there's really no excuse for not starting.

What emerges from online searches in the Richmond Enquirer is a pattern of favorable mentions of Gansevoort Melville and unaffected praise for books by Gansevoort's younger brother Herman Melville.

Mastheads of the Daily Richmond Enquirer after May 1845 list William F. and Thomas Ritchie, Jr. as co-editors. Thomas Ritchie, Jr. and William Foushee Ritchie were sons of Enquirer founder, old Thomas Ritchie. As chronicled in the Editor and Publisher and Journalist 12.2:

In May, 1845, Ritchie left the Enquirer after forty-one years of service, and went to Washington to take the chief editorial management of the Union, the official organ of President Polk.

Just before his retirement from the Enquirer in 1843, two sons. William F. and Thomas Ritchie, Jr., had been associated in the management of the paper. On the departure of his father for the National Capital, William F. Ritchie became its editor.Another version of editorial changes at the Richmond Enquirer, from The Virginia Magazine of History and Biography:

On March 4, 1843, his sons William F. and Thomas Ritchie, Jr., were admitted into partnership, and the firm of publishers became Thomas Ritchie and Sons.

On March 19, 1845, the publication of a daily edition called the Daily Richmond Enquirer was commenced, and on May 9th of the same year Thomas Ritchie retired after editing the Enquirer for forty-one years. The editors and owners were then William F. and Thomas Ritchie, Jr. The files of the paper from 1845 to 1860 are not among those in the State Library; but it is known that during this period it was owned and edited by the two Ritchie brothers.The Richmond Ritchies were associated with Gansevoort Melville as active Democrats and fellow supporters of James K. Polk in the 1844 presidential campaign. The elder Thomas Ritchie, "Father" Ritchie is the "Napoleon of the press" who presided over dinner at the Exchange Hotel in Richmond on March 12, 1845 with John C. Calhoun, General Lamar, and Gansevoort Melville.

On August 5, 1844 the Richmond Enquirer reprinted the supportive column on Gansevoort from the New York Evening Mirror, backing the able new Secretary of Legation at London with special reference to the distinction of his "double revolutionary descent":

|

| Richmond [Virginia] Enquirer, August 5, 1844 via Genealogy Bank |

We are pained to learn by the last steamer, that Gansevoort Melville, Esq., of New York American Secretary of Legation at London, died in that city on the 12th ult., after an illness of three weeks. He was a gentleman of talents and high worth.On Saturday, July 4, 1846 the Enquirer copied the item from the Albany Argus reporting THE FUNERAL OF GANSEVOORT MELVILLE.

The favorable notice on June 29, 1846 by the Daily Richmond Enquirer of Herman Melville's first book Typee was lengthened by numerous excerpts from excellent reviews in other newspapers and magazines:

“Typee,” or a Residence in the Marquesas Islands.

This work, which we have read with great gratification, bids fair to acquire a most enviable popularity. It is truly a sort of New Robinson Crusoe. Its free, dashing style, and entertaining narratives and descriptions, render it at once novel and instructive. It is from the pen of Mr. Hermann Melville, of New York, a brother of Gansevoort Melville, our late accomplished and much lamented Secretary of Legation at London.

We subjoin some of the favorable opinions which this book has won in other quarters. We are proud to see that the literary genius of America is beginning to be appreciated in the Old World:

“A book full of fresh and richly colored matter. Mr. Melville’s manner is New World all over.”— [London Athenæum.

“A book of great curiosity; striking in the style of composition, many of the incidents but require us to call the savages celestials, to suppose Mr. Melville to have dropped from the clouds, instead of ‘bolting’ from the skipper Vangs, and to fancy some Ovidian graces added to the narrative in order to become scenes of classical mythology.”— [London Spectator.

“This is really a very curious book. The happy valley of our dear old Rasselas was not a more romantic or enchanting scene.” [London Examiner.

“This is a most entertaining and refreshing book. The picture drawn of Polynesian life and scenery is incomparably the most forcible and vivid that as ever been laid before the public. The writer of this narrative, though filling the post of a common sailor, is certainly no common man. His clear, lively and pointed style, the skillful management of his descriptive, the philosophical reflections and sentimental apostrophes scattered plentifully through the work, are the production of a man of letters.” [London Critic.

“These adventures are very entertaining.” [Tait’s Edinburgh Mag.

“There is no lack of incident or novelty, and he who commences the perusal of Mr.; Melville’s narrative will scarcely fail to complete it.” [London Eclectic Review.

“The scenes depicted are novel—the descriptions fresh. It is full of marvelous adventure, perilous journeyings and glowing pincillings [sic] of savage life and scenery, which possess a charm calculated to rivet the reader’s attention as strongly and continuously as De Foe’s Robinson Crusoe. There are so many passages and pages full of curious information, that our only difficulty is to abridge our extracts.” [Simmons’ Colonial Magazine.

“One of the most delightful narratives of adventure ever published. From the first line in the first page to the last in the last, interest, information, and the most genial freshness of description pervade the whole volume. Every chapter has its separate picture and every picture is glowing with life. Throughout it there are snatches of drollery that are irresistibly comic, and sometimes reflections of the most unstrained and winning pathos. We can cordially recommend the book as a most choice and delightful one: if we could possibly squeeze all its pages into a single column, we would prove its excellence by transcribing the entire work.” [London Sun.

“Since the joyous moment when we first read Robinson Crusoe, and believed it all, and wondered all the more because we believed, we have not met with so bewitching a work as this narrative of Herman Melville’s.”— [John Bull.

“The style is racy and pointed, and there is a romantic interest thrown around the adventures which to most readers will be highly charming.” [American Review.

“Those who love to roam and revel in a life purely unconventional, though only in imagination, may be gratified by following the guidance of Mr. Melville. He writes of what he has seen con amore, and his pen riots in describing the felicity of the Typees.”—[Graham’s Magazine.

"This has all the elements of a popular book—novelty, and originality of style and matter, and deep interest from first to last. Few can read without a thrill the glowing pictures of scenery and luxuriant nature, the festivities and amusements, the heathenish rites and sacrifices, and battles of these beautiful islands.” [Hunt’s Merchant’s Magazine.

“The adventures are of a youth in the romantic islands of the Pacific Ocean, among a strange race of beings, whose manners and modes of life are by no means familiar to us.”

“The scenes described with peculiar animation and vivacity, are of a description that must task the credulity of most plain matter of fact people; yet they are without doubt faithfully sketched, and afford evidence of ‘how little half the world knows how the other half lives.’ The volumes are of the most amusing and interesting description.” [Democratic Review.

--Daily Richmond [Virginia] Enquirer, Monday morning, June 29, 1846; found in the online Newspaper Archives at Genealogy BankWith a similar endorsement of the young author as representative of a growing national literature, Melville's next book Omoo also received highly favorable treatment in the Richmond Enquirer:

For Mardi, the "Checklist of Additional Reviews" in Herman Melville: The Contemporary Reviews, ed. Brian Higgins and Hershel Parker, gives the date of one notice by the "Richmond Enquirer, 11 May 1849."

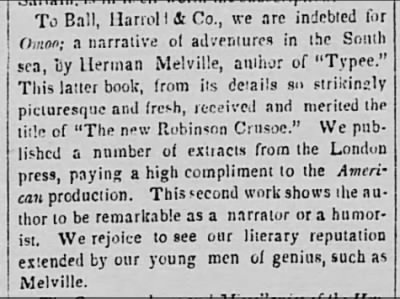

Richmond Enquirer, July 2, 1847 To Ball, Harrold & Co., we are indebted for Omoo; a narrative of adventures in the South sea, by Herman Melville, author of “Typee.” This latter book, from its details so strikingly picturesque and fresh, received and merited the title of “The new Robinson Crusoe.” We published a number of extracts from the London press, paying a high compliment to the American production. This second work shows the author to be remarkable as a narrator or a humorist. We rejoice to see our literary reputation extended by our young men of genius, such as Melville.-- Daily Richmond [Virginia] Enquirer, Thursday, July 1, 1847; reprinted the next morning, Friday, July 2, 1847. Available online via the Newspaper Archives at Genealogy Bank; and now Newspapers.com

Here is the brief take on Mardi from the Enquirer, May 11, 1849 under the heading NEW WORKS:

Wonderful to say, The 19th Century Rare Books & Photograph Shop is offering the volumes of Mardi owned by long-time editor of the Richmond Enquirer Thomas Ritchie "with his signature, and with his son’s later inscription":Mardi, and a voyage thither—a romance of Polynesian adventure, in two volumes; by Herman Melville, author of the popular “Typee.”—Same publishers [Harper & Brothers].

As two narratives of voyages in the Pacific, published by the author, had been received with incredulity, he determined to write a fiction, supposing that, vice versa, the fiction might be taken as a verity. It abounds in very spirited and graceful sketches of land and ocean, of the pursuit of the whale, &c.--found in the online Newspaper Archives at Genealogy Bank

Provenance: Thomas Ritchie (1778-1854), with his signature, and with his son’s later inscription. One of the leading American journalists of the first half of the nineteenth century, Ritchie was the longtime editor and publisher of the Richmond Enquirer, which Thomas Jefferson hailed as “the best [newspaper] that is published or has ever been published in America.” Letters to Ritchie from Herman Melville’s brother Gansevoort are in the Ritchie papers at William & Mary.A fine and tight set. Out of my league unfortunately, but it would be nice to learn something more about that later inscription--by Thomas Ritchie's son, meaning who? Thomas Ritchie, Jr. or William Foushee Ritchie?

Another place to look for favorable Melville mentions is the Richmond Examiner, edited by John M. Daniel (not W. F. Ritchie). Burton R. Pollin found a good one in Daniel's review of Redburn in the Examiner for November 23, 1849, transcribed in Melville Society Extracts 89 - June 1992. And I guess now we ought to look harder at the Washington Daily Union under the editorship of old Thomas Ritchie.