|

| Apollo of the Belvedere Livioandronico2013, CC BY-SA 4.0 via Wikimedia Commons |

Here then are three contemporary reports of Melville's 1857-8 lecture on Roman statuary from newspapers in Detroit, Boston, and Clarksville, Tennessee.

First and best is the report from Detroit, where Melville lectured on January 12, 1858. Text below is transcribed from the front-page article in the Detroit Free Press (January 14, 1858) which Sealts called

the fullest version of "Statues in Rome" published by any newspaper. --Melville as Lecturer, 36Interesting that the Detroit reporter heard "Ardua" which might tell us how Melville pronounced "Padua."

Mr. Melville’s Lecture.

On Tuesday evening Mr. Herman Melville, of Pittsfield, Mass., lectured before the Young Men’s Society. He is well known to the literary world as the author of “Omoo,” “Typee,” and “Moby Dick,” books that made some sensation a few years ago from the graphic manner in which they described scenes and incidents among the far off islands of the Pacific. Mr. Melville has roamed around in this part of the world more than any other American author, and the incidents with which he has enlivened his books have been those which he has himself experienced. The subject of his present lecture was announced as “Roman Statuary.”

Mr. Melville said that among the higher emotions is a feeling for art, and this exists wherever there is beauty or grandeur. This feeling appeals to all men. Art strikes a chord in the lowest as well as in the highest; the rude and uncultivated feel its influence as well as the polite and polished. It is a spirit that pervades all classes; but the uncultivated never express the emotions which they feel, from the fear that they may use terms that shall be unscientific and unprofessional. There are many examples on record to show this, and not only this, but that the educated are very often more susceptible to this influence than the learned. There can be no doubt that Burns saw more poetry in a single daisy than Linnaeus in all the flora of which he treated. The speaker remarked that this must be his excuse; he pretended to be no critic or connoisseur in thus attempting to speak of the statuary at Rome, and he would relate merely his own impressions in reference to it.

As you enter Rome, upon its very threshold you meet with statuary. Here are the mute citizens who will be remembered when other things in the Imperial City are forgotten. Wherever you go in Rome, in is gardens, its walks, its public squares or its private grounds, statues may be seen. They abound on every side, but by far the greatest assemblage of them is to be found in the Vatican. These are all well known by repute; they have been often described in the traveler’s record and on the historic page; but the knowledge thus gained, however perfect the description may be, is poor and meagre when compared with that gained by personal acquaintance. Here are ancient personages, the worthies of the glorious days of the Empire and Republic. Histories and memoirs tell us of their achievements, whether on the field or in the forum, in public action or in the private walks of life; but here we find how they looked, and we learn them as we do living men. Demosthenes is better known by statuary than by history. The strong arm, the muscular form, the large sinews, all bespeak the thunderer of Athens who hurled his powerful denunciations at Philip of Macedon. Just so with the chiseled Titus; his short neck, broad shoulders and thick set person make him known and appreciated.

In the bust of Socrates we see a countenance more like that of a bacchanal or the debauchee of a carnival than of a sober and decorous philosopher. It reminds one much of the broad and rubicund phiz of an Irish comedian. It possesses in many respects the characteristics peculiar to the modern Hibernian.

|

| Bust of Socrates in the Vatican Museum |

The head of Julius Caesar fancy would paint as robust, grand, and noble; something that is elevated and commanding.

But the statue gives a countenance of a business-like cast that would well befit the president of the Erie Railroad. Just such a one has Seneca, whose philosophy would be christianity itself save its authenticity. It is iron-like and inflexible, and would be no disgrace to a Wall Street broker. That of Seneca’s pupil, Nero, at Naples, done in bronze, resembles that of one of our fast young men who drive spanking teams and abound on race-courses. The first view of Plato surprises one. Engaged in the deep researches of philosophy as he was, we certainly would expect no fastidiousness in his appearance, neither a carefully adjusted toga or pomatumed hair. Yet such is the fact, and this great transcendentalist has the sleek and smooth appearance of a modern Brummel.

This subject was illustrated by instances taken in modern times with which we are all acquainted because in this way we best obtain a true knowledge of the appearance of the statue. The aspect of the human countenance is the same in all ages. If five thousand ancient Romans were mingled with a crowd of moderns, it would be difficult to distinguish the one from the other unless it were by a difference in dress. The same features—the same aspects—belong to us as belonged to them. Their virtues were great and noble, and these virtues made them great and noble. They possessed a natural majesty that was not put on and taken off at pleasure, as was that of certain eastern monarchs when they put on or took off their garments of Tyrian dye—Christianity has disenchanted many of the vague old rumors in reference to the ancients. We can now easily compare them with the moderns. The appearance of the statues, however, is often deceptive, and a true knowledge of their character is lost unless they are closely scrutinized. A lady remarked in the lecturer’s presence that the statue of Tiberius did not look so bad as he was represented; it has more of a sad and musing air. To some it would convey the impression of a man broken by great afflictions, of so pathetic a cast is it. Yet a close analysis brings out all his sinister features, and a close study of the statue will develop the monster portrayed by the historian.

The lecturer next spoke of the Apollo, the crowning glory of all, which stands alone in the Belvedere chapel of the Vatican. Every visitor rushes to the chapel to behold the statue, and, when he departs, his last glance is turned toward this loadstone. Its very presence is overawing. Milton’s description of Zephon makes the angel an exact counterpart of the Apollo.— In fact, the whole of that immortal poem, Paradise Lost, is but a great Vatican. Milton, when young, spent a year at Rome, and here he got many of those ideas from heathen personages which he afterwards appropriated to his celestials, just as the Pope’s artist converted the old heathen Parthenon into a Christian church. Lucifer and his angels cast down are taken from a group in a private palace at Ardua [Padua!]. This was sculptured out of one block by one of the later Italian artists. Three-score of the fallen lie wound together writhing and tortured, while, proud and sullen in the midst, is the nobler form of Satan.

Speaking of the Apollo reminds one of the Venus de Medici, although the one is at Rome and the other at Florence. She is no prude, but a child of nature, modest and unpretending. She is sculptured at the moment when, returning from the bath, she is surprised by an intrusion.

In a niche of the Vatican stands the Laocoon, the very semblance of a great and powerful man writhing with the inevitable destiny which he cannot throw off. Throes, and pangs, and struggles are given with a meaning that is not witheld.

The hideous monsters embrace him in mighty folds, and torture him with agonizing embraces. In all the ancient statues representing animals there is a marked resemblance with those described in the Book of Revelations. This class of Roman statuary and the pictures of the Apocalypse are nearly identical. But the ferocity in the appearance of this statuary is compensated by the pastoral nature of others. The quiet, gentle, and peaceful scenes of pastoral life are represented in some of the later of Roman statuary just as we find them described by that best of all pastoral poets, Wordsworth.

When standing within the Coliseum the solitude is great and vast, just such as one experiences when shut up in a vale of the Apennines, hemmed in by towering cliffs on every side.— But the imagination must build it as it was of old; it must be re-peopled with the terrific games of the gladiators, with the frantic leaps and dismal howls of the wild, bounding beasts, with the shrieks and cries of the excited spectators. Unless this is done, how can we appreciate the Gladiator? It was such a feeling of the artist that created it, and there must be such a feeling on the part of the visitor to view it and view it aright.

It is with varied feelings that one travels through the sepulchral vaults of the Vatican.— The statues are of various character: Hope faces Despair; Joy comes to the relief of Sorrow; Rachel weeps for her children and will not be comforted. Job rises above his afflictions and rejoices. The marbles alternate; some are of a joyous nature, followed by those that are of a sad and sombre character.

Just as a guide hurries one on through these scenes with his torch light, bringing out one statue in bold relief while a hundred or more are hidden in the gloom, so did the lecturer say it was necessary for him to do to keep within the limits of an hour.

If one stands a hundred feet in front of St.Peter’s and looks up, a vast and towering pile meets his view,—High, high above are the beetling crags and precipices of masonry, and yet higher still above all this is the dome. The mind is carried away with the very vastness. But throughout the Vatican it is different. The mind, instead of being bewildered within itself, is drawn out by the symmetry and beauty of the forms it beholds. These are of different and varied character. Remarkable, however, among all are the sculptured horses, riderless and rearing, seeming, like those of Elijah, to soar to heaven. The most of these were sculptured by the Greeks.— The horse was idealized by the ancient artist as majestic next to man, and they loved to sculpture them as they did heroes and gods. To the Greeks nature had no brute. Everything was a being with a soul, and the horse idealized the second order of animals just as man did the first.

Of the statues of large size much might be said, and that of Perseus at Florence would form a theme by itself. Prominent among the colossals, however, is that of Hercules.

This statue is not of that quick, smart, energetic strength that we should suppose would appertain to the powerful Samson or the mighty Hercules; but rather of a character like that of the lazy ox, confident of his own strength, but loath to use it. No trifles would call it forth; it is reserved only for great occasions. To rightfully appreciate this, or, in fact, any other statue, one must consider where they came from and under what circumstances they were formed. In other respects they reveal their own history.

But Roman statuary is by no means confined to the Vatican, or even to Rome itself. The villas around are filled with it, and, in these quiet retreats, we catch some of the last and best glimpses of the art. Here are found many of those trophies which have challenged the admiration of the world; here, where once exhaled sweets like the airs of Verona, now comes the deadly malaria, repelling from those ancient myrtles and orange groves, like Lucretia Borgia who invites to a feast and then destroys. One of the finest of the statues to be found in these villas is the Minerva, a creature as purely and serenely sublime as it is possible for human hands to form.

|

| Athena Albani |

Here also, is found a bust of Aesop, the dwarfed and deformed, whose countenance is irradiated by a lambent gleam of irony like that we see in Goldsmith’s. Many of these villas were built long years ago by men of the heathen school, for the express purpose of preserving these ancient works of art. The villas which were to shield and protect them have now crumbled, while most of the statues which were to be thus preserved still live on.

Here the lecturer entered upon a discussion of the festive habits of the ancients. It was not unusual for them at their feasts to talk upon the subject of death and other like mournful themes. Such topics were not considered irrelevant to the occasion, and, instead of destroying the interest of the feast by their ill timed intrusion, they rather added to it a temperate zest.

In conclusion, said Mr. Melville, since we cannot mention all the different works, let us bring them together and speak of them as a whole. It will be noticed that statues, as a general thing, do not present the startling features and attitudes of men, but are rather of a tranquil, subdued air such as men have when under the influence of no passion. They appeal to that portion of our being which is highest and noblest. To some they are a complete house of philosophy; to others they appeal only to the tenderer feelings and affections. All who behold the Apollo confess its glory; yet we know not to whom to attribute the glory of creating it. The chiseling them shows the genius of the creator—the preserving them shows the bounty of the good and the policy of the wise.

These marbles, the works of the dreamers and idealists of old, live on, leading and pointing to good. They were formed by those who had yearnings for something better, and strove to attain it by embodiments in cold stone. We can ourselves judge with what success they have worked. How well in the Apollo is expressed the idea of the perfect man. Who could better it? Can art, not life, make the ideal? Here, in statuary, was the Utopia of the ancients expressed. The Vatican itself is the index of the ancient world, just as the Washington Patent Office is of the modern. But how is it possible to compare the one with the other, when things that are so totally unlike cannot be brought together? What comparison could be instituted between a locomotive and the Apollo? The moderns pride themselves upon their superiority, but the claim can be questioned. They did, indeed, invent the printing press, but all the best thoughts that it sends forth are from the ancients, whether it be law, physics or philosophy. The deeds of the ancients are noble, and so are their arts; and as the one is kept alive in the memory of man by the glowing words of their own historians and poets, so should the memory of the other be kept green in the minds of men by the careful preservation of their noble statuary.

“When the Colisseum falls, Rome shall fall,

And when Rome, the world.”

--Detroit Free Press, January 14, 1858; found at the Detroit Free Press Archives. Many thanks to the Detroit Free Press and Michigan.com for permission to use here.And here is another, earlier report of Melville's lecture on Roman statuary, this one from the Boston Daily Evening Traveller (Thursday, December 3, 1857). Found in the Newspaper Archives at GenealogyBank.

The third lecture of the course before the Mercantile Library Association, was delivered last evening at the Tremont Temple, by Herman Melville, Esq., the author of “Omoo,” ”Typee,” &c. The audience was not so large as on the two previous evenings. “Statuary in Rome,” was the subject of the lecture.

Mercantile Library Lectures.Wednesday Evening, December 2.

Mr. Melville spoke in a clear and distinct voice. After a brief introduction, he proceeded directly to his subject. The statues in Rome, he believed, were peculiarly attractive to strangers, and the denizens of the city with whom they became best acquainted. They were scattered everywhere, and they gave to the present a better idea of the reality of the men of elder days.

In the expressive marble, Demosthenes became a present existence; so in the statue of Titus, of whom we read a dim outline in Tacitus, stood mildly before us Titus himself, with his lineaments and strength of form. In Socrates’ face we saw a countenance like a comic masque. In Julius Caesar’s statue we beheld a practical, business-like expression. In that of Seneca, whose utterances so amazed one of the early fathers that he thought he must have corresponded with St. Paul, we saw a face more like that of a disappointed pawnbroker, pinched and grieved. In Nero’s statue, at Naples, we saw only a fast and pleasant young man, such as those we saw in our day. In Plato, that aristocratic transcendentalist, we beheld a smoothness and neatness in the hair, and a beard such as would have graced a Venetian exquisite.

Yet in all these we saw but the men of to-day, so that we might believe that if a hundred men of that age should be transplanted to this, we would perceive that humanity was the same to-day as ever,—in what went to make up the basis of human character. We might learn that then, as now, appearances were deceptive. “That Tiberias,” said a lady. “It does not look bad.” If he did, he would not be Tiberias. That arch dissembler wore a sad, intellectual look, in which only deep attention perceived the sinister lines. It was beautiful in its features. But all these things told us how true was the statue to the description of the man and his character.

The Apollo, often drew the last glance of departing strangers, when bidding farewell to Rome, bearing as it did the appearance almost of divinity. It was a model for poets, and even Milton must have gleaned from these representations of the great men or the gods of ancient Rome high ideas of the grand in form and bearing. The Venus, in Florence, was beautiful, but it seemed, should a match be made between them, as if the divine was wedding one of the fair daughters of Eve. In the Venus the ideal and actual were blended, yet only representing nature in her perfection, a fair woman startled by some intrusion when leaving the bath.

The Laocoon, and its kindred class of horrible conceptions, formed the next subject of discussion, and after them, in contrast, the gentle and pastoral statues. The existence of the latter proved that the Roman people were not entirely destitute of the gentler feelings. When he stood in the Coliseum, with its walls rising round him like a mountain range, the lecturer had felt as solitary as if in some deep green valley in the Apennines. Imagination restored the arches, and then taking the statue of the triumphant gladiator from the Louvre, and that of the dying gladiator from the Capitol, as a centre piece, there sprang up around him again the mighty crowds which once peopled that vast temple. And he had felt, from the knowledge of the greater statues which existed, a belief that there were some among that gladiatorial people who beheld with horror and sadness the cruel scenes which the Coliseum had beheld.

The great square of the Vatican was next briefly described; then followed a vivid description of the statues on Mount Cavallo, in Rome, where the marble horses seemed to represent the fiery audaciousness of Roman power. The Moses, by Michael Angelo, appearing like a stern, bullying genius of druidical superstition; the Hercules rescued from the ruins of the baths of Caracalla—formed further subjects of comment. To understand the statues of the Vatican, it was necessary to visit often the scenes where they had stood, the Coliseum, which threw its shade like a mighty thunder cloud, the forum, the ruined temples, and remember all that had there taken place.

After extended allusions to all the statues and structures which we have enumerated thus far, the lecturer considered the Roman villas in a very pleasing way, and spoke also of the statues to be found in connection with them. In conclusion, some comprehensive ideas in reference to statuary, and to the influence exercised by the marble forms created by the sculptor, were advanced, and in this connection the lecturer said that as instinct is below reason, so is science below art—a proposition which caused some little discussion in several groups of homeward-bound listeners, after the lecture was closed.

On the whole it was a most interesting lecture, though too long by one-fifth, covering an hour and a quarter. The next lecture will be by George W. Curtis of New York.

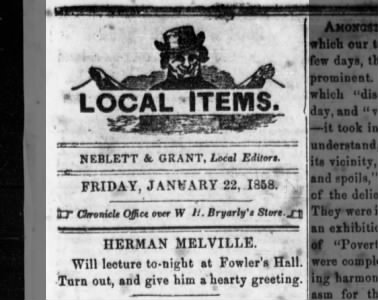

Our last item is a gem of sympathetic appreciation from the Clarksville [Tennessee] Chronicle, Friday, January 29, 1858. Accessible at the great Library of Congress site, Chronicling America.

HERMAN MELVILLE. —The Fifth Lecture to the Literary Association, was delivered on last Friday evening, by this distinguished author. With our small skill in criticism, we feel entirely unable to do justice to the production of so ripe a genius and so pure a taste. Indeed the subject was so faultless in conception and execution, that its subtle yet marvellous beauty escaped only the most appreciative sensibility and the most cultivated discernment. With that true instinct of genius, which turns aside from lofty and high sounding themes, Mr. Melville selected one of unpretending title, from which to educe noble and inexhaustible thought, and quiet, but none the less striking philosophy. His subject was "Statues in Rome;" and having been himself a wanderer in that grand old city, whose very name fires the imagination of the classic student with the magic of storied antiquity; he brought those mute forms of a distant age out of the dim and dreamy haze of fancy, into the bright and vivid light of reality. He had looked with no unthoughtful eye upon those glorious masterpieces of ancient genius from which the artists of a modern day have drawn all their inspiration. Unbiassed by the prepossessions of fancy, he traced in the marble features of those great warriors, philosophers, statesmen, and poets, whose names are now almost deified, the same lineaments of passion, and frailty, that blend in the noblest faces of our own day; and though thus stripping them of their divinity, made them dearer to us as men. The description of the ideal statuary of Rome, held us breathless by its wonderful nicety of appreciation, and subtlety of expression. Of all the tributes of genius to the Apollo, and Venus de Medici, those statues that "enchant the world," we never read one more worthy of their divine beauty. The expression of doubt, and dark groping of human speculation, in the ideal statuary of that age, when the old mythology was passing away, and men's minds had not yet reposed in the new faith, was finely portrayed. A most striking and beautiful thought was introduced, when speaking of the equestrian statues of Rome, and the expression of untamed docility, rather than conquered obedience which their artists have given to the horse, the lecturer deduced the enlarged humanity of that elder day, when man gave himself none of those upstart airs of superiority over the brute creation which he now assumes.

We do not remember in all our reading to have met with a more beautiful passage, than that in which Mr. Melville described his musings in the Coliseum, and the recurrence of his imagination far back to the day when its mighty walls enclosed such countless throngs to witness the gladiatorial combats, and the eye of fancy saw many in the vast assemblage who looked not coldly on the dying gladiator whose eyes looked far away to

——where his rude hut by the Danube lay,

There were his young barbarians all at play.

But we hung entranced upon the closing remarks of the lecturer, which vindicated these spiritual productions of the ancient mind from their alleged inferiority to the utilitarian inventions of the present age. Never before was the superiority of art over science, so triumphantly and eloquently sustained. But we will not add more of our feeble praise to a production which, if published, would elicit commendation from the highest critical sources.—

Some objected to Mr. Melville's subdued delivery; but if we rightly reflect, we will observe a striking congeniality between this quiet manner and those mute forms that stand still and silent amid the venerable ruins of "ancient Rome."

Those who appreciate the sublimity of Nature, only when the storm is loosed, and are insensible to the grandeur of her noontide silence, felt not the beauty of Mr. Melville's lecture. Those who prefer, what they term truth, and practicality and subjects of every day interest, who relish the strong meat that makes bone and muscle, above that "Nectar of the Gods" that sublimates a finer essence, tasted not of the divine chalice that the lecturer held to their lips. Mr. Melville goes from us, with the appreciation of many pure tastes, and the kindly feelings of many hearts that penetrated through the natural reserve of his character to the noble nature beneath.

Related posts:

- Statuary of Rome, Melville's 1857 lecture in Boston

https://melvilliana.blogspot.com/2019/10/statues-in-rome-lecture-boston-bee.html - Melville on Justinian and Juvenal, remembered in Minnesota

https://melvilliana.blogspot.com/2021/08/melville-on-justinian-and-juvenal.html - Melville's anti-communist math

https://melvilliana.blogspot.com/2021/08/2-2-4-melvilles-anti-communist-math.html

A related piece on Melville's lecture in New Bedford:

ReplyDeletehttps://whalingmuseumblog.org/2015/02/24/herman-melvilles-return-to-new-bedford/

Much obliged for the link to your wonderful post. I loved the entertaining newspaper account of Fowler's lecture. Also the cool images from Smith's Classical Dictionary. Thank you!

Delete