Celebrated in verse, known around Boston as the "last of the cocked hats,"

Herman Melville's paternal grandfather was also remembered as a famous fake Indian. Oliver Wendell Holmes said so in later

commentary on The Last Leaf:

"He was often pointed at as one of the "Indians" of the famous "Boston Tea-Party" of 1774."

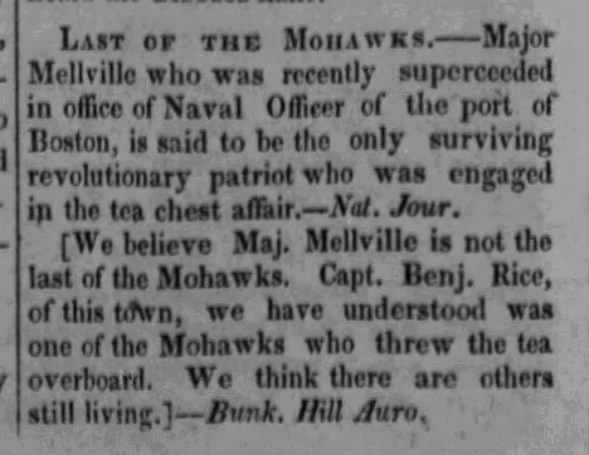

For corroboration see the following item, as reprinted in the New York Spectator from the

Washington Daily National Journal:

Major Melville, who was reformed out of the office of Surveyor of the port of Boston, by Gen. Jackson, is said to be the only surviving revolutionary patriot who was engaged in the tea chest affair. This gentleman had signalized himself by his bravery and patriotism during the Revolution. It is said that when he was unceremoniously and causelessly thrown out of the little office he filled, he shed tears, not for the loss of the office, but at the ingratitude of his country. He had looked upon his appointment to the situation as a testimony of the respect in which his last services were held, and was contented with it, although it was humble. The “Hero of two wars,” in contempt of his revolutionary services, unfeelingly threw him out, in order to pay a partisan, and the majority in the Senate, obedient to the imperial mandate, confirmed the nomination of his successor. In the beautiful language of a Senator from Kentucky, “the fine enamel of their sensibilities could not be ruffled” by the cruelty of the act.—Nat. Jonr

--New York Spectator, Tuesday, April 6, 1830; found at GenealogyBank.

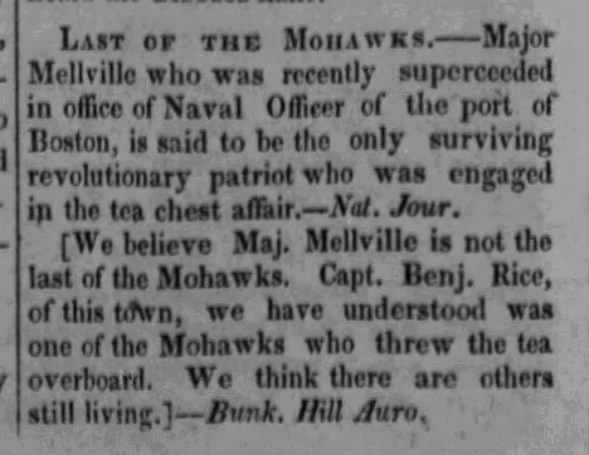

Reprinted from the

Bunker Hill Aurora in the Manchester, Vermont

Horn of the Green Mountains on April 20, 1830. The Aurora disputed the claim, commenting that "Maj. Mellville is not the last of the Mohawks."

Tue, Apr 20, 1830 – 2 · The Horn of the Green Mountains (Manchester, Vermont, United States of America) · Newspapers.com

Tue, Apr 20, 1830 – 2 · The Horn of the Green Mountains (Manchester, Vermont, United States of America) · Newspapers.com

These published treatments of Thomas Melville as a fake Mohawk, a Mock-Mohawk, call to mind the dastardly Indian chief Mocmohoc in Herman Melville's 1857 book

The Confidence-Man.

Who has noted that Mocmohoc = Mock Mohawk?

James P. Kaetz in

Melville Society Extracts Volume 79 ("Layers of Fiction," November 1989) summarizes William Ramsey on "The Moot Points of Melville's Indian-Hating," crediting Ramsey with the insight that

"the name of the treacherous Indian Mocmohoc can easily be seen as "mock mohawk" or "fake Indian."

Michael Rogin in

Subversive Genealogy is alert to the irony and potential significance of Major Melville's assumed identity:

“As Mohawks or the conquerors of Mohawks, in

the cause of American independence, the Gansevoort and Melvill grandfathers

acquired heroic power”

Some years back I quoted Rogin in a message on The Confidence-Man to the

Google group Ishmailites. Prompted by an earlier post from Clare Spark, I went on to offer a different way of reading the Mocmohoc episode as a kind of masquerade or upside-down allegory. Here it is again, cut and pasted:

Clare rightly places the “Indian-Hating” chapters in Melville’s Confidence-Man “among the most difficult chapters in a difficult book.” Her reading of the admittedly complex sequence as a critique of Rousseau, the Noble Savage, and associated notions of human goodness and divine benevolence seems plausible enough. More than a few readers take the whole Confidence-Man as a satire on American optimisms, and with good reason. Still, one has to wonder why Melville the deep thinker and gifted writer would take so much trouble merely to affirm a hackneyed Puritan stereotype of Indians as devils and thereby implicitly countenance the practical and historical annihilation of Native Americans with whom, as Clare also rightly allows, Melville on principle must have regarded sympathetically as brothers. The independent-minded and sensitive-souled writer does not, one hopes, so readily embrace commonplaces.

Let me here propose another level of meaning. Not the only level worth considering, obviously, but an important one that is consistent with Melville’s characteristic aesthetic and humanist values, and consistent also, as it turns out, with Clare’s perception of a satire on smooth optimism. Try this out. Perhaps the most atrocious incident of Indian savagery in the entire “Indian-Hating” section is the massacre perpetrated by a devilishly treacherous Indian chief named “Mocmohoc.” The tale is told in chapter 26 by a mysterious stranger (identified later on as Charles Arnold Noble) who has adopted the persona of James Hall, a real-life frontier celebrity in his own right. In brief, Mocmohoc invites his new friends the Wrights and Weavers over for a feast of barbecued bear and then slaughters them. This is too terrible. What monster could be more fiendish than the host who kills his confiding guests?

But who is this Mocmohoc? As others before now have noticed, the name “Mocmohoc” suggests a fake Indian, a Mock Mohawk. Who then are fake Mohawks? The rebellious colonists who dressed up like Indians during the famous “Boston Tea Party,” of whom Herman’s paternal grandfather Thomas Melvill made one. After the Party, ebullient Bostonians chanted “Rally Mohawks! Bring your axes, and tell King George we’ll pay no taxes,” according to Michael Paul Rogin in Subversive Geneaology (p49). Rogin goes on to observe, “As Mohawks or the conquerors of Mohawks, in the cause of American independence, the Gansevoort and Melvill grandfathers acquired heroic power” (49).

Yow! A key, and the bolt turns. The story always felt like allegory anyway, and so it is. In true allegorical fashion, something stands for something else. THIS means THAT. This Mocmohoc stands for those mock Mohawks the white English colonists and revolutionary founders of America. But the mistreated Wrights and Weavers, who are they? The Indians! Consider: the strange backstory of the five cousins allusively recalls the “Five Nations” and the Iroquois Confederacy. The word “covenant” as employed by Mocmohoc suggests the “Covenant Chain” or alliance between the Indians and English colonists. The “Albany Congress” convened in 1754 to repair the chain which Mohawk leader Hendrick had declared was broken in 1753. In the Confidence-Man it is the white prisoner of Mocmohoc who accuses him of breaking “covenant.”

In a larger view, Mocmohoc’s falsely offering to “bury the hatchet, smoke the pipe, and be friends forever” mirrors the long course of treaty making and treaty breaking pursued by the new American government. For a glimpse of Melville on the official mistreatment of Indians, we might go to Typee or, closer to home, the prairie as described in John Marr and Other Sailors:

“The remnant of Indians thereabout—all but exterminated in their recent and final war with regular white troops, a war waged by the Red Men for their native soil and natural rights, had been coerced into the occupancy of wilds not very far beyond the Mississippi...

Melville evidently likes to invert stereotypical attributes of Indians and Whites. He imputes the noblest motives to the Indians, using the noblest words and phrases. Indians are Men, fighting heroically to defend “their native soil and natural rights.” The motives that inspired the great revolutions of Europe and America, the motives that inspired Melville’s grandfathers, likewise inspired the Indians. The allegory of Mocmohoc similarly inverts the usual and expected associations. By way of Judge Hall and Charlie Noble, Melville gives us a remedial lesson in American History by turning it upside down, standing history (as told by the victors) on its head.

To get the true drift, you have to own the whiteness of Mocmohoc, and the Indian-ness of the Wrights and Weavers. -- Ishmailites