Thanks to the

thrilling finish of the first volume (1819-1851) of Hershel Parker's two-volume biography, Melville fans know "Maherbal" as the Berkshire correspondent of the Vermont

Journal who reported Melville's curiously formal dinner engagement with Nathaniel Hawthorne in the dining room of a Lenox hotel. From Lenox on January 10, 1852, "Maherbal" wrote to the Windsor, Vermont newspaper:

Not very long ago, the author of the "Scarlet Letter" and the author of "Typee," having, in some unaccountable way, gotten a mutual desire to see one another, as if neither had a home to which he could invite the other, made arrangements in a very formal manner to dine together at a hotel in this village. What a solemn time they must have had, those mighty conjurors in the domain of the imagination, all alone in the dining-room of a hotel!

Richard E. Winslow III found this and other letters from "Maherbal" in microfilm archives of the Vermont

Journal. At his blog

Fragments from a Writing Desk, Parker recounts years of searching that led to Winslow's exciting discovery.

In the same post Parker explains the evidence, chronology, and reasoning behind his depiction of the hotel scene in Volume 1 as the November 1851 "publication party" at which Melville must have presented a copy of his new book Moby-Dick to his "solitary guest," the dedicatee.

"Maherbal" wrote more of Melville in that January 1852 letter, about his reputation for "exclusiveness" in Pittsfield, about the rough treatment Melville received from unruly students in his early career as a schoolteacher. "Maherbal" wrote too of G.P.R. James and other famous Berkshire residents. In one of his earlier letters from Lenox (dated November 29, 1851), "Maherbal" had focused on Hawthorne, giving colorful details and commentary on Hawthorne's physical appearance and notoriously reclusive lifestyle.

So the other day I was playing around in the newspaper archives at

genealogybank.com.

Searching for "maherbal" (and maybe "maherbal + vermont") I found three "Letters from England" in the Vermont

Journal (September-October 1855), submitted by their old Lenox correspondent "Maherbal," who was now writing from London. No mention of Melville, but another hit for "maherbal" turned up another article in the Vermont

Journal from May 25, 1855--not a "Maherbal" letter at all, but an editorial on "America and the Russian War."

In "American and the Russian War" the editor of the Vermont

Journal replies to criticism of American newspapers by "Griffith," a foreign correspondent of another Vermont paper, the Burlington

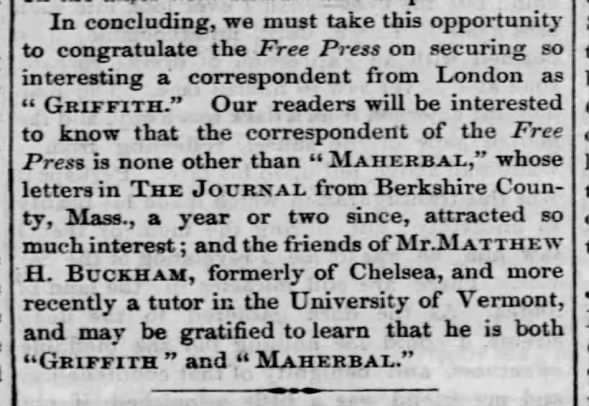

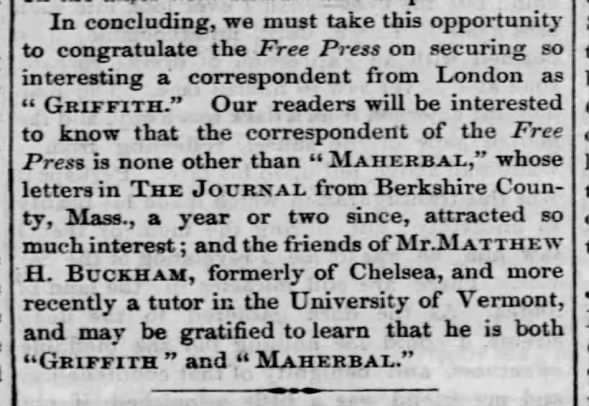

Free Press. At the end of the article the Journal editor unmasks (in a friendly way, I take it) this complaining "Griffith":

... Our readers will be interested to know that the correspondent of the Free Press is none other than "MAHERBAL," whose letters in THE JOURNAL from Berkshire county, Mass., a year or two since, attracted so much interest; and the friends of MR. MATTHEW H. BUCKHAM, formerly of Chelsea, and more recently a tutor in the University of Vermont, and may be gratified to learn that he is both "GRIFFITH" and "MAHERBAL." -- Vermont Journal, May 25, 1855

Also accessible via

Newspapers.com:

Fri, May 25, 1855 – 2 · Vermont Journal (Windsor, Vermont) · Newspapers.com

Fri, May 25, 1855 – 2 · Vermont Journal (Windsor, Vermont) · Newspapers.com

Aha! "Maherbal" =

Matthew Henry Buckham (1832-1910)

Matthew Henry BUCKHAM, of Burlington [Chittenden County, Vermont], was born 04 July 1832 at Hinckley, Leicestershire, England, son of Rev. James BUCKHAM. He pursued his preparatory studies in the academy at Ellington [Tolland County], Connecticut, and also at a private school in Canada. Entering the University of Vermont in September 1847, he graduated from it in August 1851. He was principal of the Lenox Academy at Lenox [Berkshire County], Massachusetts, from 1851 to 1853. In September 1853 he became tutor of languages in the University of Vermont. In August 1854 he sailed for Europe, spent two years there in travel and study, and returned in 1856 to enter upon a professorship in the University of Vermont. He occupied the chair of Greek in that institution from 1856 to 1871, and also performed the duties of professor of English literature from 1865 to 1871. -- Men of Vermont

|

Pittsfield Culturist and Gazette - October 1, 1851

via GenealogyBank |

Buckham was nineteen and just out of college when he became principal of the Lenox Academy and began sending letters from Lenox to the Windsor, Vermont newspaper. The

Bibliography of Vermont credits Buckham as "one of the authors of a 12mo. volume of about 200 pages, relating to Berkshire County, Mass., published in 1852 or 1853." That would be

Taghconic (1852), wherein putative author "Godfey Greylock" (real name Joseph Edward Adams Smith) credits "Mr. BUCKHAM, of Lenox" with two chapters:

10 Lenox and its Scenery

11 Lenox as a Jungle for Literary Lions

Sure enough,

chapter 11 of Taghconic contains most of Maherbal's letter dated November 29, 1851 and published in the Vermont

Journal on December 12, 1851. The following passage from

Taghconic is nearly verbatim from the

Journal, but with some interesting changes. For example, where the book version critiques Hawthorne's "unsympathising, morbid spirit," the original letter from "Maherbal" called it "a sort of dreamy, unsympathizing spirit." From

Taghconic, chapter 11, by "Mr. Buckham, of Lenox":

Mr. Hawthorne, even for a man of letters, leads a remarkably secluded life. He has a few literary friends with whom he cherishes an intimacy congenial to a mind of such cultivation and sensibility, and a friendship which does honor to his heart, but he shows no disposition to mingle largely in society. This aversion to social intercourse has been remarkable in him during his literary career, and even far back into his youth, if we may credit the accounts of his acquaintances. Not only in his private life, but all through his writings, there seems to breathe an unsympathising, morbid spirit, — a spirit that seems to take a satisfaction in keeping itself aloof from those who are guilty of the foibles which it takes a still greater satisfaction in contemplating. This spirit he could never have inherited from his ancestors, else those progenitors of his, who for so many generations " followed the sea," were a strange set of tars! Perhaps all his better sympathies were chilled in those speculations with his dreamy brethren of the Brook Farm Community; perhaps he and Emerson, enraptured with the mystic perfection of their own fantasies, abjured all communion with this our gross humanity; he certainly could not have had his feelings frozen into hate by contact with the genial and sympathizing intellect of Ellery Channing, or at the warm hearth-stone of Longfellow.

From the letter of "Maherbal" dated November 29, 1851 on "Nathaniel Hawthorne," published in the

Vermont Journal on December 12, 1851:

Mr. Hawthorne, even for a man of letters, leads a remarkably secluded life. He has, doubtless, a few literary friends, with whom he cherishes a friendship congenial to a mind of such cultivation and sensibility, but he shows no disposition to mingle in the highly intellectual society of our village, and even studiously declines any advances which are made towards a familiarity with him on the part of those whose acquaintance he might find ample reason to prize. This aversion to society has been so remarkable in him during his literary career, at least, and even far back into his youth, if we may credit the accounts of his acquaintances, that it seems to be constitutional with him. At any rate, a sort of dreamy, unsympathizing spirit, seems to breathe through all his writings, and to manifest itself in various acts of his life, as far back as we have any means of tracing it. We are sure he could not have inherited it from his ancestors, or else those progenitors of his, who for so many generations “followed the sea,” were a strange set of tars! Perhaps all his better sympathies were chilled in those speculations with this dreamy brethren of the Brook Farm community—perhaps he and Emerson, in their rapt fantasies, abjured all communion with their fellows of this our gross humanity; he certainly could not have had his feelings frozen into hate by contact with the genial and sympathizing intellect of Ellery Channing, or the warm hearthstone of Longfellow.

Possibly more of Mr. Buckham's letters from Lenox in 1851-1853 will be discovered, either in the Vermont

Journal or another Vermont newspaper. As we now know, in 1855 Buckham wrote to the Burlington Free Press under the name "Griffith." It remains to be seen whether the

Free Press ever published any communications from a Griffith, or even Maherbal, during Matthew Henry Buckham's tenure as principal of the Lenox Academy.

Bios

- Prentiss Cutler Dodge, Encyclopedia, Vermont Biography (Burlington, 1912) pages 132-133.

https://books.google.com/books?id=tt2_3hTQxFMC&pg=PA132&dq#v=onepage&q&f=false