|

| The Attack of Two Lanoon Pirate Proas on the Proa Jolly Bachelor, belonging to Rajah Brooks of Sarawack and manned by the crew. Image credit: Lebrecht Music & Arts / Alamy Stock Photo |

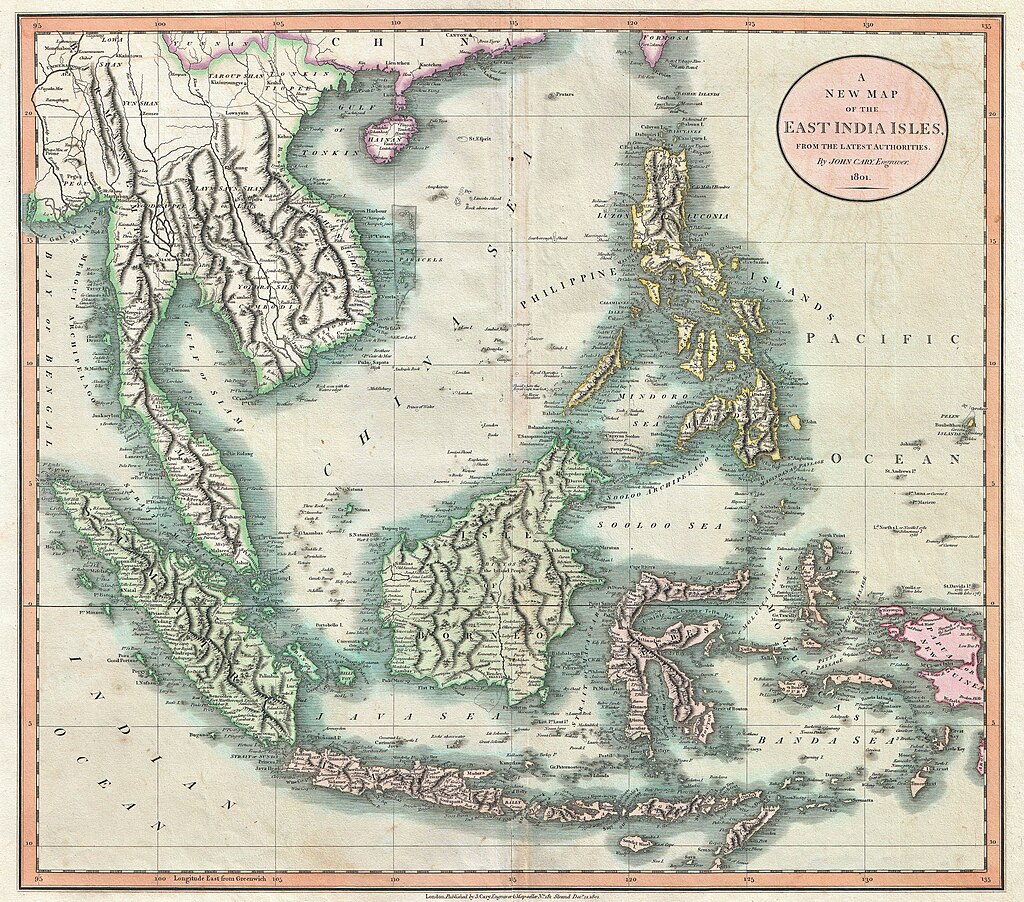

Fearing treachery from the Spanish captain of the San Dominick, Amasa Delano as portrayed in Benito Cereno thinks of pirates. Twice, at least. The last time is when Don Benito jumps into Delano's boat, and Delano melodramatically accuses him of being a homicidal "plotting pirate." Earlier, Delano mentally connected his enigmatic Spanish host with "Malay pirates" and horror "stories" of their deceptive maneuvers in what used to be called the East India Isles.

Geographically, "Malay" for Melville and his nineteenth-century audience denoted natives of Malacca, the Malay peninsula, and nearby islands in the East Indian or "Oriental" archipelago. Later designated Southeast Asia or, more broadly, Asia Pacific. As a racial construct the term Malay is (like Caucasian, as Nell Irvin Painter has explained) a legacy of pseudoscience influentially practiced by Johann Friedrich Blumenbach. John Ogilvie's 1856 Supplement to the Imperial Dictionary explicitly credits Blumenbach for the sense of MALAY as a racial classification. Herein, I mainly understand Malay pirates as a stereotype of popular culture that Melville adapts in "Benito Cereno" for distinctive literary purposes and fantastic effects.

According to Melville's Delano, one maneuver attributed to Malay pirates was feigning distress while waiting below decks with spears to attack hostile boarders by surprise:

... But then, might not general distress, and thirst in particular, be affected? And might not that same undiminished Spanish crew, alleged to have perished off to a remnant, be at that very moment lurking in the hold? On heart-broken pretense of entreating a cup of cold water, fiends in human form had got into lonely dwellings, nor retired until a dark deed had been done. And among the Malay pirates, it was no unusual thing to lure ships after them into their treacherous harbors, or entice boarders from a declared enemy at sea, by the spectacle of thinly manned or vacant decks, beneath which prowled a hundred spears with yellow arms ready to upthrust them through the mats. Not that Captain Delano had entirely credited such things. He had heard of them — and now, as stories, they recurred.--Benito Cereno in Putnam's Monthly-October 1855; and The Piazza TalesIn chapter 11 of his Narrative of Voyages and Travels (well before the Tryal matter which takes up chapter 18), Amasa Delano notes the notorious "treachery and cruelty of the Malays." He warns against landing boats in the Natuna and Anambas islands, "treacherous harbors" in Melville's words. Delano also gives practical advice for chasing off a menacing Malay fleet (fire your big guns, "soon as you can") in the Banca or Bangka Strait. But the real, historical Delano did not tell any tales about the risky business of chasing after and boarding a Malay ship.

|

| via Patricia Hului at Kajo Mag, 10 Interesting Facts about the 19th Century Iranun Pirates |

"... a very wicked, but a very clever book." -- The Spectator.

"This fanciful autobiography opens like a Marryat novel with an account of youthful hardships, pranks, and enlistment in the navy. Soon follows a racy tale of wild East Indian life, for Trelawny turns pirate, captains a crew of dare-devil Arabs, Mussulmans, Daccamen, Coolies, and Lascars, with a sprinkling of Swedes, Dutch, French, and Portuguese, and argues that in preying upon others he is but despoiling robbers. Most of his rascality proceeds, however, from unbridled passion. He plays the savage with zest, runs amuck, is devoted to wine and women, and in his thirst for liberty or license, his hatred of priests, and his romantic attachment to the Arab girl Zela is a more venturesome and less sentimental Byron." --Frank W. Chandler, The Literature of Roguery Vol. 2 (Houghton, Mifflin and Company, 1907) page 349.

Somewhere in the Laccadives (now Lakshadweep) Trelawny's Malay pirates do what Delano according to Melville only imagines:

... We approached her [unnamed ship, previously described as "a large Malay brig, full of men"] warily. Not the smallest impediment was opposed to us. Indeed nothing gave token that there was a being on board of her. I ordered the Rais, who commanded one boat, to board her on the bow with his Arabs; whilst I, with a party, chiefly Europeans, and a gallant set of fellows they were, climbed up her ornamented quarters and bamboo stern. On getting on board, we saw many dead and wounded on her deck, but nothing else. She was only about two-thirds decked, having an open waist, latticed with bamboo, and covered with mats. Her sails and yards were hanging about in confusion. We were now all on deck, and a party of men was preparing to descend between decks; when, while replying to De Ruyter's questions, I was suddenly startled at hearing a wild and tumultuous war-whoop, and springing forwards, I saw a grove of spears thrust up from below, which, passing through the matting, wounded many of our men. I was certainly as much astonished at this novel mode of warfare as Macbeth at the walking wood of Dunsinane. Running round the solid portion of the deck, several spears were thrust at me, which I with difficulty escaped. --Adventures of a Younger SonAs a teenager, the narrator of Trelawny's Adventures falls in with a devilishly charismatic and cosmopolitan privateer named De Ruyter, aka De Witt. De Ruyter himself is Dutch-American with a French commission, although personally he (much like the real Amasa Delano, later in chapter 11) disdains "the scum that the French revolution has boiled up" at the Isle of France. The "Malay brig" under attack is rumored to be loaded with plunder. After disabling the brig and attempting to board, De Ruyter's crew are astonished when Malays in hiding present them with "a grove of spears thrust up from below." Similarly, Melville's Delano conceives a surprise attack by stereotyped Malay pirates as "a hundred spears with yellow arms ready to upthrust them through the mats." Melville's figure of one hundred spears indicates he has in mind a relatively large vessel, comparable in size to the "Malay brig" described by Trelawny.

For one contemporary analogue, Hershel Parker in Herman Melville: A Biography Volume 2, 1851-1891 (Johns Hopkins University Press, 2002) pages 238-9, cites an 1847 report about Malay pirates in the New York Herald.

|

| New York Herald - December 6, 1847 Chronicling America: Historic American Newspapers. Library of Congress. |

<http://chroniclingamerica.loc.gov/lccn/sn83030313/1847-12-06/ed-1/seq-2/>This is the kind of story Melville knew from reading newspapers. But such items usually reported attacks by Malay pirates, so-called, rather than hostile attempts by privateers to capture Malay vessels as prizes of war.

The correspondences with Adventures of a Younger Son are more precise. Details that Melville's image in "Benito Cereno" shares with Trelawny's narrative include the premised attack on a Malay vessel, Malays below deck with spears, their action of thrusting spears upward, and specific mention of the mats through which they stab at enemy boarders.

Another published analogue for the "Malay pirates" ruse that Melville's Delano recalls in "Benito Cereno" appears in The Eventful Narrative of Capt. William Stockell (Cincinnati, 1840).

... we stood on towards Angry point on the island of Java. Sailing round the point where the brig was run ashore we discovered a large Malay Prow, which as soon as she saw us, swept towards the shore. We out with all boats and outflanked her, got to the shore before she did, and boarded her. Not a man was to be seen upon her deck, which was only of loose bamboo. I was one of the first on board, and received a prick of a spear through the deck. In two minutes the decks were crowded with our seamen, and the Malays below kept pushing their spears through and wounding the men. Seeing that, I jumped into our boat, took out a port-fire and hove it in amongst them, which brought them up, and they surrendered. --Eventful Narrative of Capt. William StockellAs Stockwell relates it, he was impressed at gunpoint into service on the British frigate Egeria. The attack on the "Malay brig" is featured in the synopsis for chapter 10, as follows:

In the straits of Sunda surprize and take a Malay brig.--Description of their mode of defence.

The manner of "defence" described by Stockwell is basically the same tactic employed by Malays according to Trelawny, and Melville's Delano. However, the language in Trelawny's version is closer to Melville's, particularly the locutions thrust up and matting, corresponding to Melville's "upthrust" and "mats." And Stockell's narrative was and is fairly obscure, whereas Melville clearly knew something about Trelawny. In White-Jacket Melville invokes Trelawny as a literary sailor and ultra romantic, famous (via "Mr. Trelawney's Narrative" in Leigh Hunt's 1828 volume Lord Byron and Some of His Contemporaries) for managing the cremation of Shelley.

In his illuminating study of Melville's "ethnic cosmopolitanism," Timothy Marr cites other influential presentations of Malays as "shadowy pirates of terror": Thomas de Quincey's Confessions of an Opium Eater (also cited in the editorial notes for the Hendricks House Moby-Dick) and published accounts of the Sumatran expedition by U.S. frigate Potomac, avenging the 1831 attack at "Quallah-Battoo" (Kuala Batu) on the merchant ship Friendship. Questia has "Without the Pale: Melville and Ethnic Cosmopolitanism" by Timothy Marr in A Historical Guide to Herman Melville, ed. Giles Gunn (Oxford UP, 2005).

Is it solely for the Malay, the living Ishmaelite of the world, that prolific nature has been thus bountiful? The Malay— treacherous, cruel, and vindictive as, he is—fierce and unrelenting as the tiger of his own mountains, by which he is often destroyed, —is still a being entitled to the sympathy and compassion of the civilized world; and we cannot but pity his condition, even when his vices demand a measure of punishment at our hands. How black and damning would be the page containing an account of his wrongs from boasted Christians, since the year 1510, when Albuquerque landed on his shores. For three centuries, what has been the history of Europeans trading on his coast, under the direction of heartless, grasping monopolies, but a record of oppressions, cruel exactions, and abominable injustice! To the honour of the British name, though her track in the east has, in all directions, been stained with blood, she has ever shown more humanity than either of her former powerful competitors; whose every thought, impulse, and action, appear to have been concentrated in one festering canker—insatiable avarice!The "living Ishmaelite" line was quoted in The Philadelphia Enquirer, also excerpted in Volume 7 of the New York Knickerbocker. If the Malay be a modern Ishmael, then Melville's Ishmael may be regarded as Malay, figuratively speaking. Call the Malay Ishmael my pointy-headed footnote to Spencer Tricker, "'Five Dusky Phantoms': Gothic Form and Cosmopolitan Shipwreck in Melville's Moby-Dick," recently published by Johns Hopkins University Press in Studies in American Fiction, vol. 44 no. 1, 2017, pp. 1-26. Project MUSE, doi:10.1353/saf.2017.0000. Tricker's article was recently honored with the Hennig Cohen Prize Award for opening "a radical reassessment of race in Melville’s fiction." The second part deals with "The Malay in Melville's Pacific Works," but Tricker keys on the different, earlier reference in "Benito Cereno" to "Lascars and Manilla-Men," rather than the later image of lurking Malay pirates. For historical context Tricker introduces "The Malay Pirates" in The Albion, which I see was reprinted from The United Service Journal for April 1837, published in London. (Though published in New York, The Albion was a "British, colonial, and foreign weekly gazette" that chiefly promoted British literature and interests.) Bad as they are, Malays in their lust for war and violence "remind us of our northern forefathers, the sea-kings of the olden time." Vikings, like Jarl in Mardi. An earlier survey of Oriental Pirates appeared in the September 1835 issue of The United Service Journal.

Relevant previous scholarship includes the aforementioned chapter on Melville's "ethnic cosmopolitanism" by Timothy Marr in A Historical Guide to Herman Melville, ed. Giles Gunn (Oxford UP, 2005); and Hershel Parker's reading of "Benito Cereno" in light of Melville's evolving Gothic aesthetic:

"One can measure three stages of Melville's growth between the spring of 1847 and the end of 1854--roughly, since his marriage--in the gothic chill of the passage in Mardi; then in Moby-Dick the evocative imagery of yellow peoples of the immemorial East and in Pierre the image of hooded phantoms from the unconscious disembarking in Pierre's soul; and now the gothic revisited as an illustration of the psychological and metaphysical problem of evil in the universe." --Herman Melville: A Biography Volume 2, 1851-1891 (Johns Hopkins University Press, 2002) page 239.

<https://books.google.com/books?id=5bI50n5WImkC&pg=PA239&lpg#v=onepage&q&f=false>In the summer of 1848 when Melville was deep into writing Mardi, a long discussion of "Piracy in the Oriental Archipelago" appeared in The Edinburgh Review v. 88 (July 1848): 63-94; reprinted in Littell's Living Age Volume 18 no. 222, 12 August 1848. The unsigned Edinburgh Review essay (by James St. John) was criticized in The Examiner of October 21, 1848 ("Piracy in the Eastern Archipelago"); and defended by Spenser St. John in Piracy in the Indian Archipelago, published in The Journal of the Indian Archipelago and Eastern Asia, Volume 3 (April 1849). As in the 1837 article on "Malay Pirates" in The United Service Journal, the original Edinburgh Review article traces pirate history back to the Vikings. Again, no mention that I can find of Malays lurking below deck.

But getting back to Trelawny: Henry A. Murray in 1947 credited Adventures of a Younger Son as a Byronic "prototype" for Melville's narratives of South Sea adventure:

"...the prototype of Melville's early works is Childe Harold, or, to name a more specific model flavored with Byronism, Trelawny's Adventures of a Younger Son." --Henry A. Murray, Introduction to Hendricks House edition of Pierre; or, The Ambiguities.Zela, the narrator's Arab bride in Adventures of a Younger Son, may have influenced Melville's conception of Yillah in Mardi.

My love for Zela knew no diminution. Every day I discovered some new quality to admire in her. She was my inseparable companion. I could hardly endure her out of my sight an instant; and our bliss was as perfect as it was uninterrupted. My love was too deep to fear satiety; nor did ever my imagination wander from her, to compare her with any other woman. She had wound herself about my heart till she became a part of me. Our extreme youth, ardent nature, and solitude, had wrought our feeling of affection towards each other to an intensity that perhaps was never equalled, assuredly never surpassed. <https://hdl.handle.net/2027/wu.89099222911?urlappend=%3Bseq=288>

... a light and bounding figure, with her loose vest and streaming hair flying in the wind, and in speed like a swallow,—(but oh! how infinitely more welcome than that harbinger of spring and flowers!) came all my joy, my hope, my happiness, my Zela! She sprung into my arms, we clasped each other in speechless ecstasy, and there thrilled through my frame a rapture that swelled my heart and veins almost to bursting. The rude seamen forget their danger, and looked on not unmoved. --Adventures of a Younger SonIn Moby-Dick, Ahab with his "Anacharsis Clootz deputation" of global "isolatoes" on the Pequod recalls De Ruyter with his band of exiles and outlaws--viewed later on by the eccentric surgeon Van Scolpvelt as a "barbarous crew" with "heathenish prejudices":

We had fourteen Europeans, chiefly from the dow; they were Swedes, Dutch, Portuguese, and French. We had also a few Americans, together with samples of almost all the seafaring natives of India; Arabs, Mussulmans, Daccamen, Cooleys, and Lascars. Our steward and purser was a mongrel Frenchman, the cabin-boy English, the surgeon Dutch, and the armourer and master-of-arms Germans, De Ruyter was indifferent as to where his men were born, or of what caste they were; he distinguished them by their worth alone. I was astonished at such dissimilar and incongruous ingredients being mingled together with so little contention; but it was the consummate art of the master-hand, his cool and collected manner, which regulated all: before a murmur was heard, he forestalled every complaint by a timely remedy. He himself was the most active and unwearied in toil, the first in every danger, and every thing he did was done quicker and better than it could have been by any other person. In short, he would have been, amidst an undistinguished throng of adventurers, in any situation of peril or enterprise, by a unanimous voice, their chosen leader. --Adventures of a Younger SonIn chapter 24 De Ruyter invites his protege to command "an Arab grab brig" with a mysteriously "secreted" crew of Europeans and Americans. As sailors and fighters, however, the narrator prefers "Daccamen" in "red caps, jackets and turbans."

"Besides, I like the look of those Arabs, and of those savage, lean, wild-eyed fellows, with their red caps, jackets and turbans. I never saw cleaner or lighter-made fellows to fly aloft in a squall, or board an enemy in battle.” “Yes, they are our best men, and come from Dacca; and they'll fight a bit, I can tell you.” --Adventures of a Younger SonPrimitive and nonhuman features of Trelawny's "savage" and "wild-eyed fellows" are shared by Ahab's "savage crew" (chapter 46, Surmises) of whale-hunters, depicted in chapter 36 (The Quarter-Deck) as having the "wild eyes" of prairie wolves.

As noted above, White-Jacket (A Man-of-War Race) contains the one explicit reference to Trelawny (spelled "Trelawney") in Melville's writings. Jack Chase names Trelawny in the honor roll of great sailor-writers, in between Shelley and Byron.

There's Shelley, he was quite a sailor. Shelley—poor lad! a Percy, too—but they ought to have let him sleep in his sailor's grave—he was drowned in the Mediterranean, you know, near Leghorn—and not burn his body, as they did, as if he had been a bloody Turk. But many people thought him so, White-Jacket, because he didn't go to mass, and because he wrote Queen Mab. Trelawney was by at the burning; and he was an ocean-rover, too! Ay, and Byron helped put a piece of a keel on the fire; for it was made of bits of a wreck, they say; one wreck burning another! And was not Byron a sailor? an amateur forecastle-man, White-Jacket, so he was; else how bid the ocean heave and fall in that grand, majestic way?Also in White-Jacket, Melville gives traits of Trelawny's comically severe and amputation-obsessed doctor Van Scolpvelt to navy surgeon Cadwallader Cuticle. More on Van Scolpvelt another time, hopefully.

|

| Albany Daily Argus - June 18, 1832 |

"in essence a boy's dream of heroic and romantic adventure, elaborated with the realism of a sailor, and the extraordinary power and imagination with which he was endowed by nature." --Anne Hill, Trelawny's Family Background and Naval Career, in Keats-Shelley Journal 5 (Winter 1956): 11-32 at 14.The New-York Society Library listed "Younger Son, by Trelawney, 2 vols." in their 1838 Alphabetical and Analytical Catalogue. Still there in the online NYSL Catalog, both volumes: F T CS v. 1 and F T CS v. 2. So Melville could have read or re-read them at NYSL c. 1848-50, when he lived in New York City.

A few years ago (maybe more than a decade), HP queried me about a naval bombardment of a Pacific island. I responded that in terms of naval history I thought the occurence was too frequent to allow for a definitive identification. But I've recently returned to Reynolds and the Potomac volume, which I suspect harbors more than we've dredged out of it in terms of direct influence.

ReplyDeleteBob, great to hear from you. Being a smatterer myself when it comes to naval history and lit, I only got to Reynolds' Potomac volume the back way via Trelawny's Adventures. And I only read Trelawny on the recommendation of "A Captain of U. S. Dragoons" and "I. F." = the narrator's Imaginary Friend in the September 1851 installment of "Scenes Beyond the Western Border."

ReplyDeleteI. F.—De Witt and the nameless hero, are every inch sailors and soldiers too.

"Do you remember the Malay chief and his red horse?"

I. F.—Remember them! It is a splendid picture of glorious bravery—of heroic action!

https://books.google.com/books?id=UAkNAQAAIAAJ&pg=PA570&dq#v=onepage&q&f=false

Reprinted in Part II of Scenes and Adventures in the Army (Lindsay & Blakiston, 1857) pages 254-5:

https://archive.org/details/scenesadventures00incook/page/254/mode/2up