|

| Joel Munsell, Annals of Albany v. 10 |

Stephen Van Rensselaer aka "The Patroon" (or "new patroon," after the death of Stephen Van Rensselaer III in 1839) owned a Century Plant that bloomed in September 1842 while Herman Melville was on the Lucy Ann, nearing Tahiti.

Toby's tale, written by Melville's shipmate and fellow-adventurer Richard Tobias Greene, helpfully corroborated otherwise doubtful details of their indulgent captivity in Typee. Melville needed Toby's story to authenticate his own, and so rewrote it for a sequel to the main narrative.

Sept. 13 [1842]. The American aloe, or century plant, in the patroon’s garden was now in bloom, and had the appearance represented in the engraving. This ancient denizen of the Manor garden, was purchased soon after the revolutionary war, at the sale of a confiscated estate in the city of New York. It was then a well grown plant, and had now been standing in the green house of its present owner nearly sixty years, and was supposed to be between eighty and a hundred years old. For the first time it now gave signs of putting forth a flower stem. When the bud appeared, it grew with astonishing rapidity (18 inches in 24 hours), and attained 21 feet in height; and being a novelty, for very few had ever heard that such a plant existed anywhere, the numbers which visited it were very great, many coming from a great distance—one person came from Ohio expressly to see the phenomenon. --Joel Munsell, The Annals of Albany v. 10 (Albany, 1859), 332.Melville could have read about it later, in newspapers. As Hershel Parker documents in the second volume of Herman Melville: A Biography (page 945), one reminiscence of the Patroon's glorious Century Plant appeared on the same page of the same issue of the Albany Evening Journal (July 13, 1846) with "Toby's Own Story."

|

| Albany Evening Journal - July 13, 1846 via GenealogyBank |

|

| Albany Evening Journal - July 13, 1846 |

In a letter to Evert Duyckinck written in early February 1850, Melville pictured the Century Plant or American Aloe as an emblem of literary achievement and recognition. Comparing Duyckinck's library to a patriarchal greenhouse full of "exotics and other rare things in literature," Melville offered his third book Mardi as

a plant, which tho' now unblown (emblematically, the leaves, you perceive, are uncut) may possibly--by some miracle, that is--flower like the aloe, a hundred years hence--Melville's 1850 letter to Evert A. Duyckinck in manuscript is accessible online via NYPL Digital Collections.

--Some Personal Letters of Herman Melville

"During its exhibition at Mr. Thorburn's Saloon, upwards of five thousand persons visited it." --Christian Intelligencer, December 10, 1842.By contrast, only a "few" curious "sight-seers" come to view the plant imagined in Melville's poem "The American Aloe on Exhibition."

But few they were who came to seeMelville's "American Aloe" is extant in manuscript at Houghton Library, Harvard University, with other manuscript pieces from the posthumously published collection of prose and verse titled Weeds and Wildings.

The Century-Plant in flower:

Ten cents admission—price you pay

For bon-bons of the hour.

- Persistent Link http://nrs.harvard.edu/urn-3:FHCL.HOUGH:16083258?n=293

- Description Melville, Herman, 1819-1891. Unpublished poems: autograph manuscript, undated. Herman Melville papers, 1761-1964. MS Am 188 (369.1). Houghton Library, Harvard University, Cambridge, Mass. Folder 5. Weeds & wildings with a rose or two.

Now anybody with internet can look at manuscript images courtesy of Houghton Library, Harvard University and the Harvard Mirador Viewer. Here's my rough transcription, not bothering much about erasures that you would have to examine the physical manuscript to recover, possibly.

The American Aloe

On Exhibition

[It is but a floral superstition, asalmosteverybody knows, that this plant flowersbutonly once in a century. When in any instance the flowering is for decades delayed beyond the normal period, (eight or ten years at furthest) it isof courseowing to something retarding in theindividualenvironment or soil.]

But few they were who came to see

The Century-Plant in flower:

Ten cents admission—price you pay

For bon-bons of the hour.

In strange inert blank unconcern

Of wild things at the Zoo,

The patriarch let the sight-seers stare—

Nor recked who came to view.

These seldom more than two.

But lone at night the garland sighed

AndWhile moaned the

That crowned hisaged stem:

"At last, at last! but joy and pride

What part have I with them?

Why wail the thisdearth

Let be the causedearth that kept me back

How long from wreath decreed;

But ah, ye Roses that have passed gone

Accounting me a weed!

Ah, few divine what kept me back

Cleaned up below. Of two choices for line 8 (last line of second stanza), each in its way redundant, "These seldom more than two" seems to me marginally less repetitive and therefore stronger. The handwriting just there looks bolder, too, so I'm inclined to keep it despite restore marks that justify the preference for "Nor recked who came to view" in the Northwestern-Newberry edition. Robert Faggen gives "These seldom more than two" in the 2006 Penguin edition of Selected Poems, following the 1924 Constable edition (The works of Herman Melville v.16 (London: Constable, 1924), 321. Granted, the Constable edition often proves untrustworthy. In "Aloe" alone, for example, the readings "And While" and "Now long" are wrong. Well, Hennig Cohen I see reads "Now long" in his Selected Poems of Herman Melville. But "Now" for "How" illustrates the old problem, meticulously explained by William H. Gilman in 1946: Melville's "H" looks like "N," hence the name "Norman Melville" on the crew list of the merchant ship St. Lawrence, bound for Liverpool.

The American Aloe

On Exhibition

[It is but a floral superstition, as everybody knows, that this plant flowers only once in a century. When in any instance the flowering is for decades delayed beyond the normal period (eight or ten years at furthest), it is owing to something retarding in the environment or soil.]

But few they were who came to see

The Century-Plant in flower:

Ten cents admission—price you pay

For bon-bons of the hour.

In strange inert blank unconcern

Of wild things at the Zoo,

The patriarch let the sight-seers stare—

These seldom more than two.

But lone at night the garland sighed

While moaned the aged stem:

"At last, at last! but joy and pride

What part have I with them?

Let be the dearth that kept me back

How long from wreath decreed;

But ah, ye Roses that have passed

Accounting me a weed!"

As presented in Melville's "Aloe" poem, the exhibition is cheap (10 cents) and poorly attended. He can't have in mind the sensationally popular exhibit of the Patroon's Century Plant in 1842, unless he never learned how well attended it really was. Not likely that Melville remained so ignorant, since the wondrous Albany Century Plant was still remembered in 1872, decades after it flowered in Stephen Van Rensselaer's garden.

Some thirty years since, one of these century plants, which had been in the house of Van Rensselaer, the "Patroon of Albany," since the days of the Revolution, burst into bloom, and the event was the wonder of the season in scientific and refined society, hundreds of visitors from all parts of the United States coming to look upon and marvel at the mysterious plant, which, had it the power.of speech, might have told them of "the little birds that sang a hundred years ago" around it in its native land of sunshine and of flowers—far-distant Mexico. To those who had never looked upon its like before, and never might again, its name had a deep significance, for it was, in very truth, a century plant. It is no novelty to Californians, as it may be seen in the garden of almost every extensive private residence; but there are many facts connected with it which are not familiar to a majority of our readers. --The Overland Monthly Volume 9 - July 1872The magnificent plant of Melville's "American Aloe," like the rarer achievements of art that it represents (or has often been taken to represent), does have admirers, the "few" spectators whom the unnamed "patriarch" beholds like The Maldive Shark or The Berg or Bartleby's Wall Street wall: showing no human empathy for viewers or their feelings, only "strange inert blank unconcern." Few as they are, even these admirers are regarded as "sight-seers," tourists.

Critics occasionally relate Melville's "American Aloe" poem to the 1876 American centennial. In Clarel, Melville's ironic, isolated use of the aloe figure anticipates and effectively subverts the patriotic main conceit of more than one 1876 poem. Take, for example, "The Blossoming of the Aloe," originally published in the July 1876 issue of The Aldine, The Art Journal of America:

"Ah, no! The aloe blooms! And here to-day

A great Republic wears its starry crown

More proudly than a monarch on his throne,

While nations come to praise its grand array!

Thu, Sep 7, 1876 – Page 1 · The News Journal (Wilmington, New Castle, Delaware, United States of America) · Newspapers.com

Thu, Sep 7, 1876 – Page 1 · The News Journal (Wilmington, New Castle, Delaware, United States of America) · Newspapers.com

In "Blossoming of the Aloe"

The aloe blooms!And similarly in "The Century Plant,"

The time approaches—nay 'tis now,Whereas in Clarel (1876), crazy monkish writing on the wall looks for a scar ("cicatrix") at best:

In which the flowers should appear,

And thirteen buds are opening wide

Our hopes to fill, our hearts to cheer;

Watch, brothers, watch, the time draws near

In which the century flowers appear. --John Cruikshank, Washington, D. C. Capital, May 28, 1876.

—What's hereSo the aloe image in Clarel Part 3 Canto 27 presents a plant unable to bloom, as Cody Marrs observes in Clarel and the American Centennial, Leviathan 13 (October 2011) at 105. In Melville-Habbibi's darkly prophetic vein, the blighted century-plant figures the century-old nation, scarred and stunted by civil war. But that aloe is a cryptically expressed metaphor. That aloe is not our "American Aloe on Exhibition" in Melville's uncompleted "Weeds and Wildings" project. This aloe flowers, however belatedly. And talks about it.

Half faded:'. . . teen . . six,

The hundred summers run,

Except it be in cicatrix

The aloe—flowers—none.'—

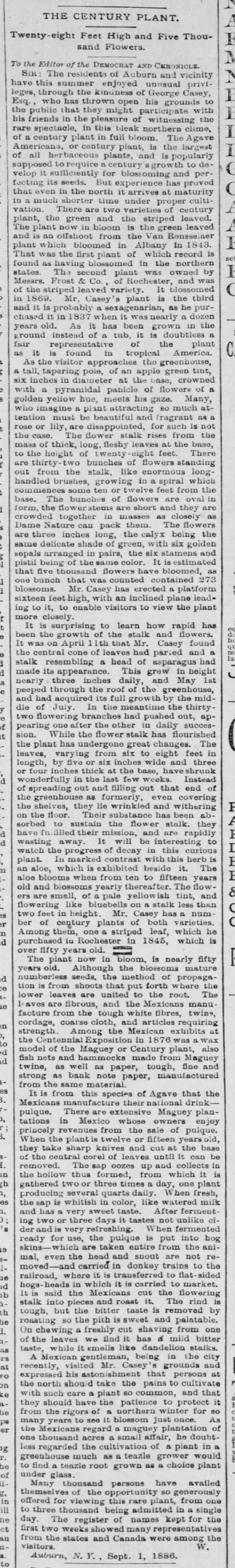

In 1886, thousands flocked to view an offshoot of the Patroon's Century Plant exhibited in Auburn, New York by one George Casey, Esq. Generous and mindful of guests, so nothing like Melville's stony "patriarch,"

Mr. Casey has erected a platform sixteen feet high, with an inclined plane leading to it, to enable visitors to view the plant more closely. --Rochester, NY Democrat and Chronicle, September 3, 1886

Fri, Sep 3, 1886 – Page 3 · Democrat and Chronicle (Rochester, Monroe, New York, United States of America) · Newspapers.com

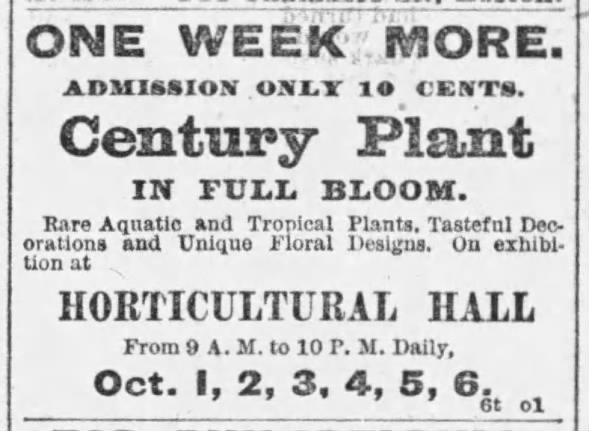

Fri, Sep 3, 1886 – Page 3 · Democrat and Chronicle (Rochester, Monroe, New York, United States of America) · Newspapers.comTwo years later in Boston, the advertised price of admission ("ONLY 10 CENTS"), matched the cheap ticket that Melville posits in "American Aloe." Thousands came to see that blossoming century plant at Horticultural Hall: 7000 persons in one afternoon according to the Boston Globe of September 26, 1888.

Thu, Oct 4, 1888 – 7 · The Boston Globe (Boston, Suffolk, Massachusetts, United States of America) · Newspapers.com

Thu, Oct 4, 1888 – 7 · The Boston Globe (Boston, Suffolk, Massachusetts, United States of America) · Newspapers.com

Where on earth is the counterpart of Melville's "patriarch"? Maybe nowhere. After all, "American Aloe" is a work of imagination. And no century plant really soliloquizes at night like the one in Melville's poem. Still, I can't help wondering: was there ever a real exhibition of a real century plant, in Philadelphia, 1876 or anywhere, anytime, to which "few" people came?

|

| Century Plant - Floral Hall Courtesy of The Library Company of Philadelphia |

|

| New York World - May 18, 1872 |

|

| New York Commercial Advertiser - July 12, 1872 |

|

| New York World - July 16, 1872 |

The century plant on exhibition in East Thirteenth street is just now at its best--the stalk showing the perfect flowers, the buds, and the clusters part blown. The plant was brought from Jacksonville, Fla., is twenty-five feet high, and contains about five thousand flowers and buds upon its stalk. The flowers are of sulphurish hue, and the stamens resemble those of a lily. Considering that it dies as soon as it has flowered, the question arises, Was it worth while to live so long to accomplish so little?

No comments:

Post a Comment