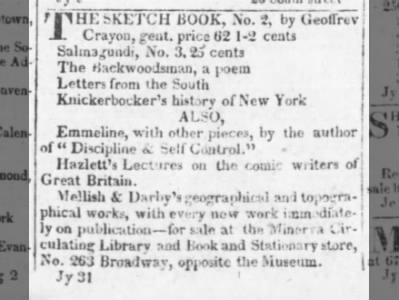

August 1, 1819 was a Sunday, so there was no Evening Post in New York City on the day Herman Melville was born. Ads on Saturday and Monday show what the Minerva Circulating Library and Book and Stationary store had for sale at 263 Broadway.

|

| New York Evening Post - Monday, August 2, 1819 |

Contents of Number One, published May 15, 1819:

The Author's Account of Himself

The Voyage

Roscoe

The Wife

Rip Van Winkle

Contents of Number Two, published in July 1819:

English Writers on AmericaIn his 1859 lecture on Travel, Melville approvingly paraphrased from Irving's chapter "The Voyage," first published in the year of Melville's birth:

Rural Life in England

The Broken Heart

The Art of Book Making

One must not anticipate unalloyed pleasure. Pleasure, pain and profit are all to be received from travel. As Washington Irving has remarked, the sea-voyage, with its excitements, its discomforts, and its enforced self-discipline, is a good preparation for foreign travel. --Melville's Lecture on TravelEveryone knows about Rip Van Winkle. Herman Melville would remake Irving's popular legend in "Rip Van Winkle's Lilac," part of the manuscript prose and poetry collection (posthumously published) titled Weeds and Wildings. Not so well known today is Irving's investigation into "The Art of Book Making." What Irving uncovered at the British Library and amusingly described was the practice by "predatory authors" of stealing material from old books to manufacture new ones.

Being now in possession of the secret, I sat down in a corner, and watched the process, of this book manufactory. I noticed one lean, bilious looking wight, who sought none but the most worm-eaten volumes, printed in black letter. He was evidently constructing some work of profound erudition, that would be purchased by every man who wished to be thought learned, placed upon a conspicuous shelf of his library, or laid open upon his table; but never read. I observed him, now and then, draw a large fragment of biscuit out of his pocket, and gnaw; whether it was his dinner, or whether he was endeavouring to keep off that exhaustion of the stomach, produced by much pondering over dry works, I leave to harder students than myself to determine.

There was one old getleman in bright coloured clothes, with a chirping, gossipping, expression of countenance, who had all the appearance of an author on good terms with his bookseller. After considering him attentively, I recognised in him a diligent getter up of miscellaneous works, that bustled off well with the trade. I was curious to see how he manufactured his wares. He made more stir and show of business than any of the others; dipping into various books, fluttering over the leaves of manuscripts, taking a morsel out of one, a morsel out of another, “line upon line, precept upon precept, here a little and there a little.” The contents of his book seemed to be as heterogeneous as those of the witches' cauldron in Macbeth. It was here a finger and there a thumb, toe of, frog and blind worm’s sting, with his own gossip poured in like “baboon's blood,” to make the medley “slab and good.

After all, thought I, may not this pilfering disposition be implanted in authors for wise purposes; may it not be the way in which providence has taken care that the seeds of knowledge and wisdom shall be preserved from age to age, in spite of the inevitable decay of the works in which they were first produced. We see that nature has wisely, though whimsically, provided for the conveyance of seeds from clime to clime, in the maws of certain birds; so that animals, which, in themselves, are little better than carrion, and apparently the lawless plunderers of the orchard and the cornfield, are, in fact, nature's carriers to disperse and perpetuate her blessings. In like manner, the beauties and fine thoughts of ancient and obsolete writers, are caught up by these flights of predatory authors, and cast forth, again to flourish and bear fruit in a remote and distant tract of time. Many of their works, also, undergo a kind of metempsychosis, and spring up under new forms. What was formerly a ponderous history, revives in the shape of a romance—an old legend changes into a modern play—and a sober philosophical treatise furnishes the body for a whole series of bouncing and sparkling essays. Thus it is in the clearing of our American woodlands; where we burn down a forest of stately pines, a progeny of dwarf oaks start up in their place; and we never see the prostrate trunk of a tree, mouldering into soil, but it gives birth to a whole tribe of fungi.

Let us not, then, lament over the decay and oblivion into which ancient writers descend; they do but submit to the great law of nature, which declares that all sublunary shapes of matter shall be limited in their duration, but which decrees also, that their elements shall never perish. Generation after generation, both in animal and vegetable life, passes away, but the vital principle is transmitted to their posterity, and the species continues to flourish. Thus, also, do authors beget authors, and having produced a numerous progeny, in a good old age they sleep with their fathers, that is to say, with the authors who preceded them—and from whom they had stolen.

--Washington Irving on The Art of Book Making

"The Art of Book Making" was reprinted with the review of Irving's Sketch Book in The London Literary Gazette for April 8, 1820.

Pitching Omoo, his second book, Melville wrote his publisher John Murray in July 1846 that

Pitching Omoo, his second book, Melville wrote his publisher John Murray in July 1846 that

"A little experience in this art of book-craft has done wonders." --The Letters of Herman MelvilleMelville evidently meant that his new manuscript would look better and be much closer to finished than were the messy and insufficient pages of Typee. Omoo would not need significant rewriting, padding, expurgating or editorial fixing. Irving's sense of book-making as stealing remains in play, nevertheless. In Omoo Melville creatively adapted numerous scenes from William Ellis and other writers on the South Seas. Hendricks House editors Harrison Hayford and Walter Blair aptly call Melville's way with other people's words, "dramatizing." On occasion Melville dramatized "spectacularly" from his source in Polynesian Researches, as when he describes night fishing by torch-light in Chapter 70, Life at Loohooloo.

Two days after Herman Melville's birth, the Evening Post extensively reviewed the second number of Irving's Sketch Book.

Found on Newspapers.com

In Melville and Repose, John Bryant devotes a whole chapter to The Example of Irving. There Bryant specifically discusses the influence of Salmagundi, and Knickerbocker's History of New York, both of which made the short list of works for sale at the Minerva Circulating Library, along with the new number of The Sketch Book.

Rarely mentioned in Melville criticism are the two works by Irving's good friend and literary collaborator James Kirke Paulding, sandwiched in the Minerva ad between Salmagundi No. 3 and Irving's History of New York. Below, links to some digitized volumes that are available online.

"The literary ambition of Mr. I. aims simply at a flute accompaniment, in our national concert of authors, leaving to the more aspiring the management of louder instruments. We gladly perceive, that he never suffers himself to be allured from his natural character, by a pompous display of his subject, or by an attempt to plunge his readers into the unfathomable depths of learning and research...."In closing, the reviewer (Henry Brevoort, so identified by Ralph M. Aderman in Critical Essays on Washington Irving) picks up on Irving's expose of authors and book-making, hoping that Irving will not imitate the practice he witnessed in the British Library, but carry on in his own modest and distinctively charming way.

We reverence the cause of true science; nor would we be understood to scoff at its unaffected votaries; but no one knows, who has not essayed the task, how cheaply an author may decorate his pages with the scattered fragments of learning, lying so invitingly at his mercy, in the multitudinous transactions and encyclopedias of our times. Our author has found out the art of book-making; he has traced to their fountain head, those muddy rills of knowledge that sometimes spread themselves even in America. It is not impossible, therefore, that in the future numbers of his work, he may avoid the labor of writing from the resources of his own mind, by compiling the present state of the Catholic question—the vast results of polar expeditions; or, peradventure, strike out some new geological hypothesis which shall reject the vulgar agency of fire or water. In such ambitious speculations, we fear, the admirers of his fine genius, might seek in vain for his sportive humor; his nice discrimination of character; his romantic associations of thought and language; his pure and affecting morality, and all the nameless graces of style, so appropriate to the captivating path of literature he has chosen to pursue.

--New York Evening Post, August 3, 1819Evert Duyckinck was right on many levels when he wrote in his diary that Melville

"models his writing evidently a great deal on Washington Irving...." --Melville in His Own Time, edited by Steven Olsen-SmithFor further study...

In Melville and Repose, John Bryant devotes a whole chapter to The Example of Irving. There Bryant specifically discusses the influence of Salmagundi, and Knickerbocker's History of New York, both of which made the short list of works for sale at the Minerva Circulating Library, along with the new number of The Sketch Book.

Rarely mentioned in Melville criticism are the two works by Irving's good friend and literary collaborator James Kirke Paulding, sandwiched in the Minerva ad between Salmagundi No. 3 and Irving's History of New York. Below, links to some digitized volumes that are available online.

- Letters from the South courtesy of the Internet Archive. Originally published in two volumes,

Letters from the South, Volume 1 via Google Books; and

Letters from the South, Volume 2 via Google Books

No comments:

Post a Comment