In the second volume of Abraham Lincoln: A Life, historian Michael Burlingame cites a newspaper clipping of an 1879 letter to the editor of the Chicago Tribune in which Lincoln's friend Herrring Chrisman (1823-1911) recalled the president-elect's determination, early in 1861, to conciliate pro-Union Virginians. The scene that Chrisman wrote about happened in Springfield, Illinois before Lincoln left for Washington, and before the Virginia Secession Convention. Professor Burlingame quotes the part of Chrisman's published reminiscence that detailed specific actions Lincoln would commit to for the sake of preserving the Union, including his promises to enforce the Fugitive Slave Act and "protect slavery" where it legally existed already:

"Tell them I will execute the fugitive slave law better than it has ever been. I can do that. Tell them I will protect slavery in the states where it exists. I can do that. Tell them they shall have all the offices south of Mason's and Dixon's line if they will take them. I will send nobody down there as long as they execute the offices themselves." --Abraham Lincoln: A Life, Volume 2, page 120In Lincoln and the Civil War, Professor Burlingame summarizes Lincoln's stand, repeating the key concessions in the order that Chrisman gave them in 1879:

Lincoln evidently believed that if he could frame an inaugural address that was conciliatory enough for Southern Unionists, yet firm enough to satisfy Republican hard-liners, and then show the South by his actions--enforcing the Fugitive Slave Law, not interfering with slavery in the states where it existed, not appointing antislavery zealots to federal posts in the Southern states--that he was no John Brown, then the crisis would pass. --Lincoln and the Civil WarMore recently, Daniel W. Crofts in Lincoln and the Politics of Slavery has referenced Lincoln's vow to "protect slavery," footnoting the source as "an 1879 recollection by H. Chrisman" by way of Burlingame in Abraham Lincoln: A Life, volume 2.

Professor Burlingame does not deal with all of Chrisman's letter. Professor Crofts cites Burlingame for the good evidence of Lincoln's pragmatism, without elaborating on Chrisman's 1879 letter. Crofts does cite important corroborating evidence of Chrisman's role, in letters from H. Chrisman to William C. Rives written in early February 1861, extant among the William Cabel Rives papers in the Library of Congress. Neither historian mentions the "look of unutterable grief" that Chrisman observed on Lincoln's face. According to Chrisman, Lincoln's expression of "mournful sadness" reflected his private expectation of failure in the effort to prevent civil war. Chrisman attributed Lincoln's gloom to his understanding that southerners would not finally abide the restriction of slavery to slave-holding states in the South.

In reporting Lincoln's promises to Virginia Unionists and the anguish they evoked in the president-elect, Chrisman also quoted Lincoln as saying something never attributed to him since:

"slavery is a sin."

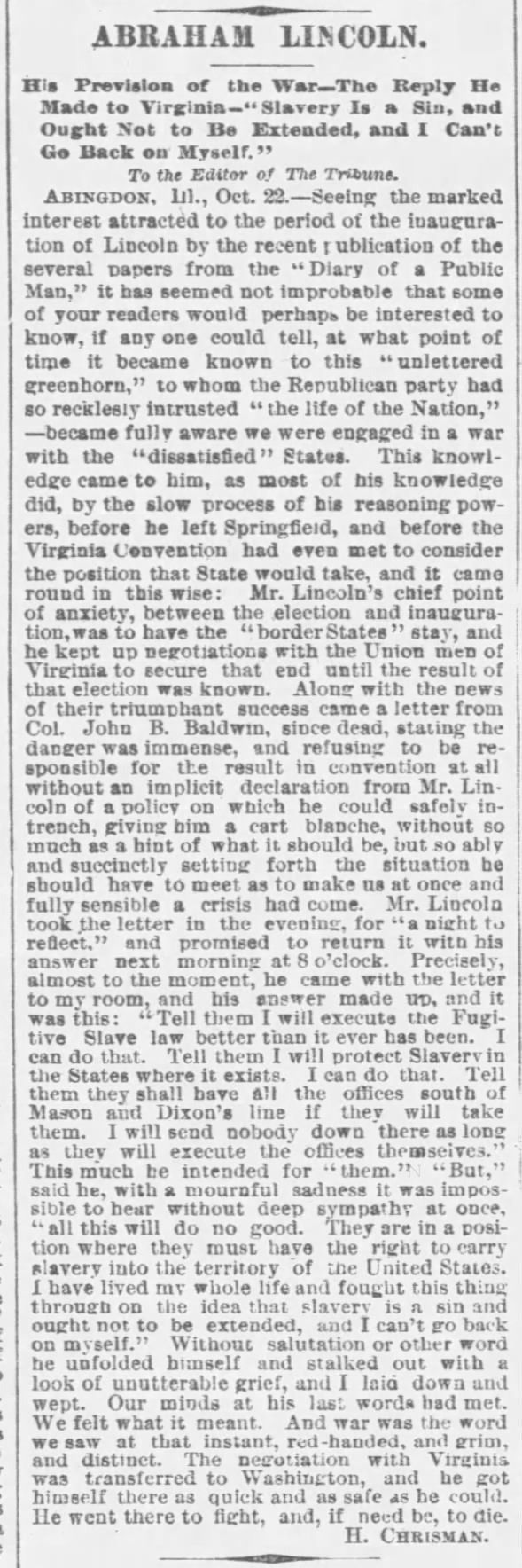

Sat, Oct 25, 1879 – 11 · Chicago Tribune (Chicago, Cook, Illinois, United States of America) · Newspapers.com

Sat, Oct 25, 1879 – 11 · Chicago Tribune (Chicago, Cook, Illinois, United States of America) · Newspapers.comABRAHAM LINCOLN.

His Prevision of the War—The Reply He Made to Virginia—"Slavery Is a Sin, and Ought Not to Be Extended, and I Can't Go Back on Myself."

ABINGDON, Ill., Oct. 22.—Seeing the marked interest attracted to the period of the inauguration of Lincoln by the recent publication of several papers from the "Diary of a Public Man," it has seemed not improbable that some of your readers would perhaps be interested to know, if any one could tell, at what point of time it became known to this "unlettered greenhorn," to whom the Republican party had so recklessly intrusted "the life of the Nation," —became fully aware we were engaged in a war with the "dissatisfied" States. This knowledge came to him, as most of his knowledge did, by the slow process of his reasoning powers, before he left Springfield, and before the Virginia Convention had even met to consider the position that State would take, and it came round in this wise: Mr. Lincoln's chief point of anxiety, between the election and inauguration, was to have the "border States" stay, and he kept up negotiations with the Union men of Virginia to secure that end until the result of that election was known. Along with the news of their triumphant success came a letter from Col. John B. Baldwin, since dead, stating the danger was immense, and refusing to be responsible for the result in convention at all without an implicit declaration from Mr. Lincoln of a policy on which he could safely intrench, giving him a cart blanche, without so much as a hint of what it should be, but so ably and succinctly setting forth the situation he should have to meet as to make us at once and fully sensible a crisis had come. Mr. Lincoln took the letter in the evening, for "a night to reflect." and promised to return it with his answer next morning at 8 o'clock. Precisely, almost to the moment, he came with the letter to my room, and his answer made up, and it was this: "Tell them I will execute the Fugitive Slave law better than it ever has been. I can do that. Tell them I will protect Slavery in the Sates where it exists. I can do that. Tell them they shall have all the offices south of Mason and Dixon's line if they will take them. I will send nobody down there as long as they will execute the offices themselves." This much he intended for "them." "But," said he, with a mournful sadness it was impossible to hear without deep sympathy at once, "all this will do no good. They are in a position where they must have the right to carry slavery into the territory of the United States. I have lived my whole life and fought this thing through on the idea that slavery is a sin and ought not to be extended, and I can't go back on myself." Without salutation or other word he unfolded himself and stalked out with a look of unutterable grief, and I laid down and wept. Our minds at his last words had met. We felt what it meant. And war was the word we saw at that instant, red-handed, and grim, and distinct. The negotiation with Virginia was transferred to Washington, and he got himself there as quick and as safe as he could. He went there to fight, and, if need be, to die.To the Editor of the Tribune.

H. CHRISMAN. --Chicago Tribune, October 25, 1879.Chrisman's published letter was widely reprinted in contemporary newspapers under the heading "A Reminiscence of Lincoln"; for example in the New York Times on Friday, October 31, 1879; the Daily Saratogian on November 6, 1879, the Cleveland Leader on November 7, 1879, the Staunton Spectator (Staunton, Virginia) on November 11, 1879, and the Philadelphia Inquirer on November 26, 1879. Various reprintings do not always include the writer's published signature, "H. Chrisman," but the ones I have seen all include the statement attributed to Lincoln that "slavery is a sin and ought not to be extended." Below, Chrisman's letter as reprinted in the Staunton Spectator, November 11, 1879; accessible online via Chronicling America, Library of Congress.

|

| Staunton Spectator - November 11, 1879 |

"We were both of Southern blood and knew what the South would do."In the introductory note to the 1930 volume Memoirs of Lincoln, J. Houston Harrison (like Chrisman in the body of his memoirs) seems keen to emphasize not only Lincoln's friendship with Herring Chrisman, but also his kinship as the grandson of Bathsheba Herring. This Bathsheba was the sister of Herring Chrisman's maternal great grandfather:

Through her marriage to Captain Abraham Lincoln, their son Thomas, the President's father, inherited maternal strains of Colonial ancestry among the most prominent in Old Augusta, later Rockingham County, Virginia.--Introduction, Memoirs of LincolnThe revised version keeps the essential point about Lincoln's non-negotiable stand on the extension of slavery "into the territories," but drops altogether Lincoln's quoted conviction that "slavery is a sin."

That letter was submitted to him as soon as it came to my quarters at the hotel. It was received late at night. He asked to take it for reflection and promised his answer at eight o'clock in the morning. Promptly to the hour he came stalking gloomily in, and without salutation sat down upon the bed and began to deliver himself with great solemnity in this wise: "You may tell them I will protect slavery where it exists; I can do that. You may tell them I will execute the fugitive slave law better than it ever has been; my people will let me do that. You may tell them they shall have all the offices south of Mason's and Dixon's line if they will take them. I will send nobody down there to interfere with them." He then remarked to me personally, and in a tone that pierced me almost like the faint wail of a suffering infant, and with a look of anguish I shall never forget: "But all of that will do no good. They have got themselves to where they might have the right to carry slavery into the territories, and I have lived my whole life and fought this campaign; and I can't go back on myself." Of course we both of us felt, and knew, it meant War. We were both of Southern blood and knew what the South would do. He went as he came, and I wept. Our minds had met. It was the first time either of us had allowed ourselves to look that awful War squarely in the face. He could have seen nobody to consult, and in so vital a matter he would wish to consult only himself.

--Memoirs of Lincoln, by Herring ChrismanWhy did Chrisman omit "slavery is a sin" in revision? Perhaps Chrisman felt he had made an error in 1879 and wanted to correct it in the 1900 version. On reflection he may have thought it a mistake to have made Lincoln utter such a familiar tenet of abolitionism. On the other hand, maybe the deleted quote was accurate but deemed regrettable, in hindsight. Several chapters in Chrisman's Memoirs exude nostalgia for the old South. The new century found Chrisman prone to condone the institution of slavery and even to idealize it. Whatever Lincoln thought, Chrisman by 1900 plainly did not regard slavery as inherently sinful. Thus, both the added emphasis on southern kinship and the deletion of Lincoln's view of slavery as a sin might have been motivated by a revived identification with southern culture and causes by Herring Chrisman himself, or by his son, or possibly by others in the family.

The volume Memoirs of Lincoln as published by his son documents southern alliances throughout, for example when John Houston Harrison points out that Herring Chrisman's brother George Chrisman served as a Major in the Confederate army. More revealingly, the chapter on Vital Causes of Our Civil War develops Chrisman's hopelessly racist and ultra-romantic defense of slavery as ideally practiced in the southern states, before the mania for "expansion" pervaded and doomed the South. Nevertheless, before and after the 1860 election Chrisman the Virginian was also a loyal Unionist with a job to do. As narrated in "The Hope of Saving Virginia" and elsewhere in the Memoirs of Lincoln, Chrisman had to empower pro-Union Virginians and thereby hold off increasingly militant secessionists in his native state, incited by Jefferson Davis. The mission as Chrisman conceived it, and expressed it to Lincoln in that Springfield hotel room, was to "save the Capitol for his inauguration" (Memoirs of Lincoln - page 87) through relentless personal diplomacy (unrewarded and unacknowledged in the public sphere, as he reflected many decades later). In Chrisman's view, his good work of supporting and placating Virginia Unionists over many months, although ultimately ineffective, at least ensured that militants in Richmond would not have the backing to attack Washington by force before the inauguration.

In any case, as far as I can tell, no subsequent version contains the lost words "slavery is a sin" that Herring Chrisman in 1879 attributed to president-elect Lincoln.

Available online via The Library of Congress:

The Abraham Lincoln Papers at the Library of Congress include in the category of "General Correspondence" a letter of support from Herring Chrisman to Abraham Lincoln, received evidently in February 1861. Below, my transcription:

Hon A. LincolnOn September 17, 1862 Orville H. Browning wrote Abraham Lincoln, forwarding him an encouraging letter from Herring Chrisman dated September 12, 1862. Here is my transcription of Chrisman's letter to Browning:

Dear Sir

This letter will be handed you by my father. We have sustained a loss by his withdrawal as candidate for the convention. I learn his vote would have been almost unanimous. He goes to tender you his friendly offices with the people of Virginia adopting fully my personal sentiments towards you.

When you visit Virginia you will come to understand the absorbing interest I feel in your personal glory. It is in no idle sense then that I rejoiced in your evident selection of the Father of his Country for your model. The grand secret of his wonderful success seems to be owing to two habits-- First to balance & adjust his powerful judgment like a pair of scales-- 2nd to invite a free discussion or rather a free expression to himself of all shades of opinion from the wise and the good of all parties-- & lastly to follow implicitly his own enlightened judgment under God, regardless of everything personal to himself excepting his honor.

With the happiest reliance as well upon your faculties as your dispositions and with the most earnest prayers for your successful administration and future happiness

I have the honor &c.

Your friend

Herring Cushman

St. Augustine - Knox Co.

September 12, 1862

Dear SirFound on Newspapers.com

You seem a little surprised at the generous warmth everywhere manifested by the democrats towards the President. I have watched its steady growth among them and believe it to be very general. It grows out of a personal trust they repose in him that he will preserve the constitution at every hazard. It seems to be his natural prerogative to be popular. He is always most so when he is most like himself. The strong man of the administration among the people in doubtful matters the Cabinet cannot do better than follow his judgment. Like General Jackson in that he seems certain to be endorsed by the people.

He has saved us from anarchy & ruin at home, given us a united North, preserved the government perfect in all its parts & satisfied the world we are still a first rate power.

There are it seems not a few who insist he must hazard all this upon a theory. Some apprehension was felt that he might be misled by this clamor. Hence the general joy over the letter to Greeley-- so calm so cool so gentle yet so firm, it satisfied the Country he was still himself. How much depends upon his life.

Your presence among the people is producing a good effect. Many good people who were being misled will see things more as they are, hereafter. The radical leaders begin already to call themselves administration men, a fact we were in danger of forgetting if indeed they were not themselves. The administration is too strong for them & they know it. Their role will now be support to betray. They will aim to borrow what strength they can from the administration to get votes to control it. My best wishes attend you.

Very truly,

Herring Chrisman

No comments:

Post a Comment