|

| Cleopatra before Caesar / Jean-Léon Gérôme, 1866 |

NUDE ART IN NEW YORK.

The Scenes at the Theater Comique

N. Y. World, Dec. 9

The following letter was the other day received at the World office:

“MR. EDITOR: Are public theatricals and unlimited license synonymous terms? If so, I can comprehend why Matt Morgan thrusts upon the public his nude and suggestive figures daily and nightly.

Please reply through your columns, or give this an insertion in your valuable journal, and oblige

AN OLD SUBSCRIBER.”

At a question so intricate as one pertaining to license, limited or unlimited, and in view of the recent action of the authorities, it was deemed best to dispatch a trusty reporter with instructions to inquire rigidly into the matter. One who had visited the Jardin Mabille, had attended trials of repute, and yawned at the “Black Crook” in all its original splendor, and fallen asleep over the impassioned strains of the “Timblale d’Argent,” was selected as a person capable of doing equal justice to unalloyed art and decency. It being a day of matinees, this reporter hastened yesterday afternoon to the seat of the present alleged immorality, the Theatre Comique, and making known his business, was politely shown to the office of Mr. Matt Morgan.

“I have come,” began the reporter, “to inquire, in the interest of public morals, whether your exhibition at this house, or that particular portion of your exhibition styled the ‘beautiful pictures,’ is—er?”

“No, it isn’t.”

“Oh! Well, is it—er?”

“No, it is not.”

“Umph! Well, then, what is it?”

“It’s an attempt (and here Mr. Morgan gathered himself upon his toes) to educate the American mind.”

“To educate the—“

“American mind, sir.”

“And is—er—nudity essential to the education of the American mind, Mr. Morgan?”

“Parbleu! It’s ‘nudity,’ always ‘nudity.’ Sir, have you an esthetic instinct? Would you see Cleopatra in the presence of the mighty Caesar decked out with a panier and pinback? Would you have Diana and her nymphs clad in gray flannel bloomers? Could you expect Phryne to appear before the Tribunal in a costume of Worth’s latest design?”

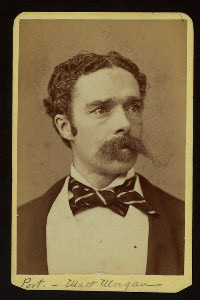

Here Mr. Morgan paused for breath, and the reporter entered the theatre to discriminate for himself. After enduring the eccentricities of numerous negro and Celtic characters for the space of an hour, the curtain at last rose upon the first of the “beautiful classic pictures.” “Cleopatra before Caesar.” To any one familiar with the original painting, it is but necessary to say that an exact counterpart was given to flesh and blood; to others it may be described as a tall symmetrical woman standing before the representative Caesar, clad in so fine and superior an article of flesh-colored silk and illusion lace mingled in the same mysterious way. Roughly estimating it, about seven-tenths of Cleopatra’s divine figure was exposed to public scrutiny. Surrounding the whole a broad frame was placed, while a suitable back-ground, painted by Matt Morgan, gave the whole a good deal of the appearance of mere paint and canvas. To the strains of Strauss the second picture was unveiled, entitled “The Shower of Gold.” On an Oriental divan reclined a Circassian blonde, whose sole raiment was a blue silk parasol held at a comfortable distance above her head by an African slave. Around about the divan in graceful postures clustered other females, each of whom exhibited a degree of pink skin tights commensurate with the size of her person. In surveying this work of art it was a matter of some perplexity to reconcile the picture with Mr. Morgan’s statement that he has “added to the drapery of the figures considerably.” Since his difficulty with the authorities. Another picture was the “Slave Merchant,” and still another “Diana and her Nymphs Surprised.”

|

| Diana and her Nymphs surprised by Satyrs / Peter Paul Rubens, 1638-40 |

“Now, sir,” said Mr. Morgan briskly, as the reporter wended his way from the art gallery, “you have seen the performance; do you see anything immoral or indecent in it?” Without waiting for a reply, the artist relieved the embarrassment by continuing: “Of course you don’t; and I intend to exhibit these pictures as long and as often as I choose. Diana in a bathing suit, or Cleopatra in a crinoline! Bah? It’s shocking, and no-where but in the prurient mind of the Young Men’s Christian Association would the idea be tolerated.”And you wonder why I would rather live in the 19th century? Not just for Morgan's classical tableaux at Theatre Comique, but also for the glorious newspapers with writing like this.

We're only showing what Matt Morgan was about in the years when Melville and Walt Whitman most likely visited his New York studio. For the record, the story so far:

Looks like McDougall's references to Walt Whitman in the Mercury and This is the Life! might be new all around, to Whitman studies as well as Melville studies. Also a new discovery, Matt Morgan's offer in April 1876 to host a benefit performance for Whitman at the Lyceum Theater.

Related posts at melvilliana:

No comments:

Post a Comment