Many commentators have noticed thematic and other parallels between representations of Agatha in

Melville's Agatha letters to Hawthorne and Hunilla in the

eighth sketch of The Encantadas. In his

1951 biography, Leon Howard observed that

"Through the character of Hunilla, in the eighth of his sketches, Melville at last managed to get his admiration for a strong patient widow into print."

--Leon Howard - Herman Melville, page 210

Howard went on to wonder if "Melville had hoped to let the Hunilla story carry the narrative burden of his book." That question in 1951 appeared "impossible to determine," but it is remarkable that Howard even ventured to raise the conjecture that Hunilla, like Agatha, might once have been envisioned as the heroine of a book-length work.

This of course was decades before

Hershel Parker's momentous find in the NYPL Augusta Papers of two 1853 references to

"Isle of the Cross" in letters from Herman Melville's cousin Priscilla to his sister Augusta.

Below, the start of a bibliography of published criticism linking the Agatha and Hunilla stories...

Agatha and Hunilla

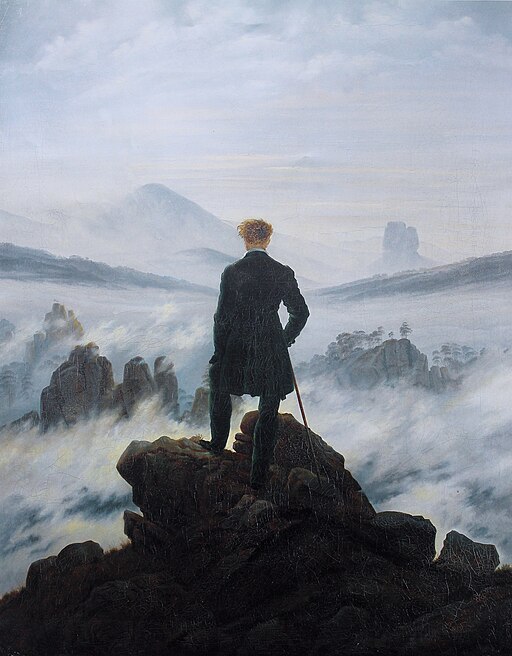

One cannot help thinking that whatever the fate of "The Isle

of the Cross," Melville's "Agatha" writing may have been part of what

became "The Encantadas; or, Enchanted Isles," published in Putnam's

in March, April, and May 1854.... "Sketch Eighth" of "The Encantadas,"

"Norfolk Isle and the Chola Widow," is most easily imagined as part of

"The Isle of the Cross" project in that the principal image for Norfolk

Island is the "rude cross" (155) that the Chola Widow has put up as

memorial for her dead husband Felipe....

...

What the "Agatha" story suggests, and the "Norfolk Isle and the Chola

Widow" enacts, is the theme that "uncomplaining submission" is the

admirable human reaction to the horror of a world in which God is

silent.

Bickley, R. Bruce, Jr.

The Method of Melville's Short Fiction. Durham, North Carolina: Duke University Press, 1975. See 18; and 115-116.

Dillingham, William B.

Melville's Short Fiction, 1853-1856. Athens, Georgia: University of Georgia Press, 1977.

"Like all else in 'The Encantadas,' the story of Agatha—warmly

humane and basically optimistic in outlook—was metamorphosed in the crucible

of Melville’s suffering into dark and barren tragedy." --William B. Dillingham,

Melville's Short Fiction - page 101

Ekner, Reidar. "The Encantadas and Benito Cereno: On Sources and Imagination in Melville."

Moderna Språk 60.3 (1966): 258-273.

Fredricks, Nancy. "Melville and the Woman's Story."

Studies in American Fiction

Volume 19, Number 1, Spring 1991. Reprinted in

Herman Melville: New Edition, ed. Harold Bloom (Infobase Publishing, 2008).

"It is not clear whether Melville ever did write Agatha's story. A variant of the tale appears in "The Encantadas" in the story of Hunilla, the Chola woman and turtle hunter who witnesses the drowning of her husband and survives alone for years on a remote, uninhabited island." --Nancy Fredricks, Melville and the Woman's Story in Harold Bloom, ed., Herman Melville: A New Edition, page 116. A revised version of this passage appears in chapter 9 of Nancy Fredricks' book Melville's Art of Democracy (University of Georgia Press, 1995), with "turtle hunter" deleted.

Hayford, Harrison.

"The Significance of Melville's 'Agatha' Letters." ELH 13.4 (December 1946): 299-310. In a footnote, Hayford makes the connection to Hunilla:

“It is possible that Agatha would have belonged not with

Billy Budd but rather with Bartleby and Hunilla, creations of the following

year…” (304 fn 13)

Howard, Leon.

Herman Melville: A Biography. Berkeley and Los Angeles: University of California Press, 1951. 210.

Hoyle, Norman E.

"Melville as a Magazinist." Unpublished doctoral dissertation. Duke University, 1960. See pp. 107-108 for prescient

discussion of Agatha and Hunilla.

Kelley, Wyn.

Herman Melville: An Introduction. Blackwell Publishing, 2008. 108-110.

Lacy, Patricia.

The Agatha Theme in Melville's Stories.

The University of Texas Studies in English 35 (1956): 96-105.

Lee, A. Robert. "Voices Off and On: Melville's Piazza and Other Stories." In

The Nineteenth-Century American Short Story. London and Totowa, N.J.: Barnes and Noble, 1986. 76-102; see 89.

López Liquete, Maria Felisa. "When Silence Speaks: The Chola Widow" In

Melville and Women, ed. Elizabeth Schultz and Haskell Springer. Kent, Ohio: Kent State University Press, 2006. 213-228.

"The Harpers also supposedly rejected 'The Agatha Story,' which relates directly to Sketch Eighth, as well as 'The Tortoise Hunters,' which relates to 'The Encantadas.'"

(227, fn8)

Ra'ad, Basem L.

"'The Encantadas' and 'The Isle of the Cross': Melvillean Dubieties, 1853-54. American Literature 63 (June 1991): 316-323.

Robertson-Lorant, Laurie.

Melville: A Biography. Amherst: University of Massachusetts Press, 1996. 338.

This sketch ["Norfolk Isle and the Chola Widow"] seems to incorporate both the Agatha story and "The Isle of the Cross." (338)

Sattelmeyer, Robert, and James Barbour.

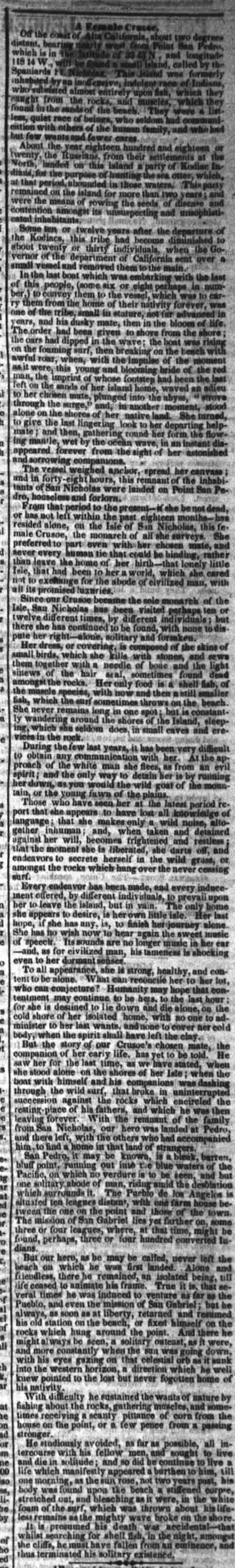

"The Sources and Genesis of Melville's 'Norfolk Isle and the Chola Widow.'" American Literature 50 (November 1978): 398-417. Sattelmeyer and Barbour introduce and discuss newspaper accounts from late 1853 concerning a "Female Robinson Crusoe"; as hinted

here, Sattelmeyer and Barbour do not mention an even earlier report of the same "Female Crusoe" (before she was "found" again in 1853), originally published in the Boston Atlas and reprinted in

Littell's Living Age 12 (March 27, 1847): 594-595. The 1847 and 1853 stories are different reports, I now realize, about the same woman on the same island of Saint or San Nicholas--elusive with no wish to leave the island in 1847, but lately discovered and "rescued" in 1853. More on all that later, hopefully. For the earlier newspaper account, see this Melvilliana exclusive

See also the post on

early sources for Melville's Chola Widow sketch for more thoughts on the Sattelmeyer and Barbour article.

Sealts, Merton M., Jr. "Historical Note"

in Melville's

The Piazza Tales

and Other Prose Pieces, 1839-1860. Ed. Harrison Hayford, Alma A. MacDougall, and G. Thomas Tanselle. Evanston and Chicago: Northwestern University Press and The Newberry Library, 1987. Sealts observes

"echoes of the 'patience, & endurance, & resignedness' Melville associated with Agatha in much of the fiction he was to write over the next three years" including "above all, Hunilla...." (483)

"Security in tortoises." http://melvilliana.blogspot.com/2013/02/security-in-tortoises.html

Smith, Herbert F. "Melville's Master in Chancery and His Recalcitrant Clerk." American Quarterly 17 (Winter 1965): 734-741.

Watson, Charles N., Jr. “Melville’s Agatha and Hunilla: A Literary Reincarnation.” English Language Notes 6 (December 1968): 114-118.

Wheeler, K. M. 'The Half Shall Remain Untold': Hunilla of Melville's Encantadas. Journal of the Short Story in English 52 (Spring 2009).

Related posts: