the matter and sources of Melville's

"In the Prison Pen (1864)"

Meager were his looks;

Sharp misery had worn him to the bones.

--Shakespeare, Romeo and Juliet - Act 5 scene 1

... like lean rows of broken-hearted pelicans on a beach; their pockets loose, hanging down and flabby, like the pelican's pouches when fish are hard to be caught. --Herman Melville, Pierre or The Ambiguities (1852) page 362.

A penitential bird indeed, fitly haunting the shores of the clinkered Encantadas, whereon tormented Job himself might have well sat down and scraped himself with potsherds. --Melville, The Encantadas, or Enchanted Isles - Sketch Third, Rock Rodondo in Putnam's Monthly March 1854; reprinted in The Piazza Tales (1856) at page 309.

Wie kann es sein, dass Gefangene überhaupt hungerten, und warum zieht man den, von dem hier die Rede ist, zum Skelett abgemagert aus der Menge, als ob sie ihn zerdrückt hätte?

--B. S. Orthau and B. Oskars, „In the Prison Pen“: ein Gedicht und sein Hintergrund in TraLaLit, 30 June 2021 - Essay

Carol Rumens, award-winning poet and Bangor University Professor, has lately showcased Melville's heartbreakingly bleak Civil War poem In the Prison Pen as her Guardian Poem of the week. Besides attending to the form of the poem (ballad stanza) and its point of view, her reading nicely highlights Melville's deployment (deemed mostly effective) of poetic language and devices including strategic use of monosyllables, vivid diction ("gashed and hoar" prisoners, looking like ghosts), inversion (the old literary trick of putting adjective after noun, as in "faces dim"), bestial imagery (the words pen and lair and den signifying the captive soldier's "reduction from human to animal") and repetition (chiefly of throngs and dead in the final stanza).

'Tis barren as a pelican-beach.

Professor Rumens does not fail to address the pelican in the first stanza, where Melville or his speaker compares the desolate place of the prisoner's confinement to the "barren" emptiness of a pelican-beach, whatever that is.

"The third-line simile needs a footnote I’m unable to supply. What is a pelican-beach?"

Wondering the same, I thought it might prove useful to investigate further and attempt an answer. In a footnote, ideally, to be constructed after I get over the mild shock of discovering that somebody wanted one. Let me begin by observing that a pretty good footnote--or end-note, technically speaking--already exists in the 2009 Northwestern-Newberry edition of Melville's Published Poems (Volume 11 in The Writings of Herman Melville) edited by Robert C. Ryan, Harrison Hayford, Alma MacDougall Reising, and G. Thomas Tanselle.

In this the most scholarly edition of Melville's Battle-Pieces to date, the relevant editorial note to "IN THE PRISON PEN" appears on page 653 (of 940) citing a biblical example of Melville's figurative pelican:

DISCUSSIONS. 86.3 barren as a pelican-beach] Psalm 102: 'I am like a pelican of the wilderness: I am like an owl of the desert." Melville marked the next verse "I watch, and am as a sparrow alone upon the house-top") in one of his Bibles (see the discussion at 64.0 above).

You can't blame Carol Rumens or The Guardian for ignoring it, not when Hershel Parker, General Editor of Published Poems, did likewise. Ever keen to break new ground, Parker chose not to bother about "pelican-beach" in his end-note to "In the Prison Pen" for the 2019 Library of America edition Herman Melville: Complete Poems, pages 944-945, and thus removed any temptation to cross-reference Psalm 102. To the same effect, the "sparrow alone upon the house top" cited in the longer Northwestern-Newberry discussion of "The House-top, another poem in Battle-Pieces, has flown. Alas! no feather of a sparrow, pelican, owl, or any other trace of Psalm 102:6 made it into Parker's generally excellent end-notes for the LOA edition.

Nevertheless, the dropped cross-reference to Psalm 102, verse 6 "I am like a pelican of the wilderness" pointed up a biblical text that is and always will be rich with significance for a sympathetic reading of "In the Prison Pen." Conventionally presented in KJV chapter headings as "A prayer of the afflicted, when he is overwhelmed," the whole of Psalm 102 could be seen to resonate with the sorrowful plight of severely maltreated prisoners.

"It is calculated for an afflicted state, and is intended for the use of others that may be in the like distress." -- Matthew Henry, An Exposition of the Book of Psalms (London, 1853).

Also by way of allusion, this time unmistakable, the Psalms of David come into play again in the fourth stanza of Melville's poem. As there shown with blunt clarity and precision, no divine protection from the "smiting sun" like that promised to the righteous in Psalm 121:6 ("The sun shall not smite thee by day, nor the moon by night.") is available to the poor soldier confined in Melville's shelterless and godforsaken prison pen.

Pelicans elsewhere in Melville's writings are almost always portrayed as sad, pitiable creatures whose angular forms and typically empty pouches make them look eternally lean and hungry. Repeatedly, Melville labels the pelican

lugubrious which according to Webster's 1848

American Dictionary means "Mournful; indicating sorrow." Along with deep sadness, usual associations for Melville include food or the lack of it, poverty, hunger, remote island habitats, desolation, arrangement in ordered rows, especially of soldiers or monks, penance, endurance of Job-like suffering, Hell.

In Pierre (1852) Melville likened undernourished philosophers and would-be social reformers, living cheaply in the "Church of the Apostles" but here lined up on the curb outside a diner, to

"lean rows of broken-hearted pelicans on a beach."

Melville's figuration of pelicans as mournful objects of condemnation and punishment is most overt in the following passage from

The Encantadas,

Sketch Third, Rock Rodondo:

But look, what are yon wobegone regiments drawn up on the next shelf above? what rank and file of large strange fowl? what sea Friars of Orders Gray? Pelicans. Their elongated bills, and heavy leathern pouches suspended thereto, give them the most lugubrious expression. A pensive race, they stand for hours together without motion. Their dull, ashy plumage imparts an aspect as if they had been powdered over with cinders. A penitential bird indeed, fitly haunting the shores of the clinkered Encantadas, whereon tormented Job himself might have well sat down and scraped himself with potsherds.

Thus represented in military and monastic metaphors as "wobegone regiments" of pitifully sad and abandoned creatures arranged in "rank and file," Melville's battle-worn and scourged penitents of pelicans seem the very emblem of suffering in captivity. Here then and without meaning to we have stumbled upon the perfect footnote to pelican-beach, already provided by Melville himself in "The Encantadas." A pelican-beach might be any blank shore unprotected from the elements where rows of mournfully sad, tormented, perpetually lean and hungry-looking creatures have been condemned to stand, endure inexplicable punishment and inevitably die. Specifically with respect "In the Prison Pen," Melville's simile in the third line figures the locale of a Southern prison as a remote hellscape or wasteland, and its forlorn captives as a penal colony of sorrowful and probably starving pelicans.

Allusion to the afflicted supplicant as "a pelican of the wilderness" in Psalm 102.6 would complement Melville's more private symbolism, although elements of Melville's favored cluster of associations with

pelican can also be found in other works, notably

The Pelican Island (1827) by James Montgomery and Thomas Beale's

The Natural History of the Sperm Whale (1839), both quoted (in connection with whales, not pelicans) in the

Extracts section of

Moby-Dick.

Closer to home lurks a possible local allusion. The depiction of Virginia's

Belle Isle Prison in the James river as

"a low, sandy, barren waste, exposed in summer to a burning sun, without the shadow of a single tree"

Whatever else it may suggest, Melville's pelican imagery as adapted to "In the Prison Pen (1864)" figuratively represents the maltreated prisoner in his place of confinement. Through allusion to the "pelican of the wilderness" in Psalm 102, Melville's pelican-beach simile links the emaciated body of the psalmist to the emaciated bodies of Union soldiers released from Belle Isle and other southern prisons, pictured in words and engraved images as "living skeletons" in the 1864 Narrative of Privations and Sufferings.

As I write, 160 years after its publication, multiple copies of the 1864 volume edited by Valentine Mott et al. are being offered by antiquarian booksellers via abebooks.com. The most valuable ones still have the original four illustrations of emaciated men, formerly prisoners-of-war. These engraved images were all made from photographs now accessible online via the Library of Congress.

Mathew Henry, again, on the extremely gaunt figure of the psalmist in Psalm 102:

"His body was macerated and emaciated, and he was become a perfect skeleton, nothing but skin and bones."

In a recent essay for TraLaLit, B. S. Orthau and B. Oskars understand Melville's "pelican beach" as a possible allusion to Belle Isle Prison at Richmond, Virginia. Along with a verse translation of "In the Prison Pen" in German, their 2021 contribution „In the Prison Pen“: ein Gedicht und sein Hintergrund introduces historical context needed just to begin to comprehend the suffering that Melville has poetically depicted. In the hosts of "plaining ghosts" surrounding the prisoner in Melville's third stanza, Orthau and Oskar find allusion to Dante's Inferno as well as Virgil's Aeneid. Their essay in German indiscriminately treats conditions in Northern and Southern prisons as essentially the same, without reference to the 1864 investigation and report by the U. S. Sanitary Commission. Nevertheless, Orthau and Oskar have boldly stated what I take herein to be the main question posed at the close of Melville's poem:

How can it be that prisoners were starving at all, and why is the person in question pulled out of the crowd, emaciated to a skeleton, as if they had crushed him? -- https://www.tralalit.de/2021/06/30/in-the-prison-pen/ +Google Translate

Also confronting the issue of starvation in southern prisons, Martin Griffin in

Ashes of the Mind: War and Memory in Northern Literature, 1865-1900 (University of Massachusetts Press, 2009) thoughtfully regards the human subject of "In the Prison Pen" as an "emaciated and mentally devastated prisoner in the hands of a regime that does not care about the condition or fate of those under its control." Being crucial to the setting and theme of Melville's poem, Griffin’s insights about the

atrocities at Andersonville and "death-in-life" as "the dominating motif" merit wider attention:

The poem reflects the situation that obtained in the Confederate prison camp at Andersonville in Georgia, a site of starvation and disease that cost the lives of over twelve thousand Union soldiers....The possibility of a kind of death-in-life, of life as a death-in-waiting, becomes the dominating motif of "In the Prison Pen (1864.)"

--Martin Griffin, Ashes of the Mind, page 88.

After the war, Henry Wirz, "keeper of the Andersonville rebel prison pen" was hanged "for inhuman treatment, resulting in numberless deaths, of the captives in his charge" as reported in the New York Daily Herald on November 11, 1865.

As pointed out in the aforementioned editorial notes to "Prison Pen" in the back of the Northwestern-Newberry edition of Published Poems, Melville's go-to source for other poems in Battle-Pieces reprinted lengthy and frequently horrifying testimony before the U. S. Senate on "The Returned Prisoners"; available to Melville in the Rebellion Record: A Diary of American Events volume 8, edited by Frank Moore, Document 2, pages 80-98. While these first-hand accounts in the Rebellion Record are obviously relevant to the hellish experience Melville poetically depicts, the 1864 Narrative of Privations and Sufferings will be shown to exhibit more and better verbal correspondences to "In the Prison Pen."

The official report by the U. S. Sanitary Commission, generously quoted in newspapers and magazines, documented and condemned the severe maltreatment of Union soldiers in Rebel prisons, most notoriously Belle Isle in Virginia and Andersonville in Georgia.

Littell's Living Age no. 1066 (November 5, 1864) contains the main report; two weeks later (November 19, 1864)

Littell's gave

the Appendix supplemented by the

Deposition of Private Tracy and other new information about the "Sufferings of the Prisoners at Andersonville, GA." Substantial excerpts were also available in major U.S. newspapers including the New York

Times on September 5, 1864 and New York

Tribune, in the semi-weekly edition of November 8, 1864. In

Battle-Pieces Melville has assigned "In the Prison Pen" to 1864 and arranged it to appear between

Sheridan at Cedar Creek dated "October 1864" and

The College Colonel, about a wounded officer and former POW who had experienced "lean brooding at Libby" prison in Richmond, Virginia. Before composing "In the Prison Pen" Melville evidently had read some version of the 1864

Narrative of Privations and Sufferings, as indicated by correspondences of language and imagery in each of its five stanzas.

In the Prison Pen

(1864)

LISTLESS he eyes the palisades

And sentries in the glare;

’Tis barren as a pelican-beach —

But his world is ended there.

Nothing to do; and vacant hands

Bring on the idiot-pain;

He tries to think—to recollect,

But the blur is on his brain.

Around him swarm the plaining ghosts

Like those on Virgil’s shore—

A wilderness of faces dim,

And pale ones gashed and hoar.

A smiting sun. No shed, no tree;

He totters to his lair —

A den that sick hands dug in earth

Ere famine wasted there,

Or, dropping in his place, he swoons,

Walled in by throngs that press,

Till forth from the throngs they bear him dead —

Dead in his meagerness. [spelled meagreness in Battle-Pieces]

Text via Poetry Foundation:

The fourth stanza of "In the Prison Pen" calls attention to the attenuated physical forms of men kept in outdoor prison-pens like Belle Isle and Andersonville. Melville's captive soldier is pictured as the victim of unrelieved "famine" that has "wasted" his body, along with disease and extremes of temperature. Formerly, when he was only sick from the filth of his environment, and not yet too weak, too hungry, and too brain-damaged to move, the prisoner could at least dig a hole in the ground for some protection from the elements. These and other key details poetically mirror the accounts of maltreatment in the 1864

Narrative of Privations and Sufferings. Specific parallels to the language and imagery of Melville's poem in the 1864 report by the U. S. Sanitary Commission are shown below, with links to digital versions of cited passages, accessible online via Google Books, HathiTrust Digital Library, and the Internet Archive. Words shared between the 1864

Narrative and Melville's "Prison Pen" include forms of

idiot,

sun,

shed,

tree,

totter,

dug,

faces,

famine, and the phrase

throng that pressed, echoed in Melville's phrase

throngs that press.

MELVILLE'S PRISON PEN

LISTLESS he eyes the palisades

And sentries in the glare;

NARRATIVE OF PRIVATIONS AND SUFFERINGS - Andersonville

This prison is an open space, sloping on both sides, originally seventeen acres, now twenty-five acres, in the shape of a parallelogram, without trees or shelter of any kind. The soil is sand over a bottom of clay. The fence is made of upright trunks of trees, about twenty feet high, near the top of which are small platforms, where the guards are stationed. Twenty feet inside and parallel to the fence is a light railing, forming the "dead line," beyond which the projection of a foot or finger is sure to bring the deadly bullet of the sentinel....

-- Deposition of Private Tracy, Supplement in Narrative of Privations and Sufferings, page 260; reprinted in Littell's Living Age page 410.

MELVILLE

Nothing to do; and vacant hands

Bring on the idiot-pain;

NARRATIVE OF PRIVATIONS AND SUFFERINGS - Belle Isle and Andersonville

Many had lost their reason, and were in all stages of idiocy and imbecility. -- Narrative of Privations and Sufferings page 58; Littell's Living Age page 301.

The mental condition of a large portion of the men was melancholy, beginning in despondency, and tending to

a kind of stolid and idiotic indifference. Many spent much time in arousing and encouraging their fellows, but hundreds were

lying about motionless, or stalking vacantly to and fro, quite beyond any help which could be given them within their prison walls. These cases were frequent among those who had been imprisoned but a short time. There were those who were captured at the first Bull Run, July, 1861, and had known Belle Isle from the first, yet had preserved their physical and mental health to a wonderful degree. Many were

wise and resolute enough to keep themselves occupied—some in cutting bone and wood ornaments, making their knives out of iron hoops-others in manufacturing ink from the rust from these same hoops, and with rude pens sketching or imitating bank notes or any sample that would involve long and patient execution. --

Deposition of Private Tracy, Supplement in

Narrative of Privations and Sufferings page 265;

Littell's Living Age v.83 page 414.

MELVILLE

He tries to think—to recollect,

But the blur is on his brain.

NARRATIVE OF PRIVATIONS AND SUFFERINGS - Libby Prison and Belle Isle

Many of them had partially lost their reason, forgetting even the date of their capture and every thing connected with their antecedent history. They resemble, in many respects, patients laboring under cretinism.

MELVILLE

Around him swarm the plaining ghosts

Like those on Virgil’s shore—

NARRATIVE OF PRIVATIONS AND SUFFERINGS - Libby and Andersonville

"They were constantly complaining of hunger; there was a sad, and insatiable expression of face impossible to describe."

-- Libby Prison described by Surgeon Nelson D. Ferguson in Narrative of Privations and Sufferings page 41; Littell's Living Age page 383.

On entering the Stockade Prison, we found it crowded with twenty-eight thousand of our fellow-soldiers. By crowded, I mean that it was difficult to move in any direction without jostling and being jostled.

-- Deposition of Private Tracy, Supplement in Narrative of Privations and Sufferings page 260; Littell's Living Age page 410.

The new-comers, on reaching this, would exclaim: "Is this hell?" yet they soon would become callous, and enter unmoved the horrible rottenness.

-- Deposition of Private Tracy, Supplement in Narrative of Privations and Sufferings page 263; Littell's Living Age page 413.

MELVILLE

A wilderness of faces dim,

And pale ones gashed and hoar.

NARRATIVE OF PRIVATIONS AND SUFFERINGS

The photographs of these diseased and emaciated men, since so widely circulated, painful as they are, do not, in many respects, adequately represent the sufferers as they then appeared.

The best picture cannot convey the reality, nor create that startling and sickening sensation which is felt at the sight of a human skeleton, with the skin drawn tightly over its skull, and ribs, and limbs, weakly turning and moving itself, as if still a living man! And this was the reality.

The same spectacle was often repeated as the visitors went from bed to bed, from ward to ward, and from tent to tent. The bony faces stared out above the counterpanes, watching the passerby dreamily and indifferently. Here and there lay one, half over upon his face, with his bed clothing only partially dragged over him, deep in sleep or stupor. It was strange to find a Hercules in bones; to see the immense hands and feet of a young giant pendant from limbs thinner than a child's, and that could be spanned with the thumb and finger!

... But however unlike and various the cases were, there was one singular element shared by all, and which seemed to refer them to one thing as the common cause and origin of their suffering. It was the peculiar look in every face. The man in Baltimore looked like the man just left in Annapolis. Perhaps it was partly the shaven head, the sunken eyes, the drawn mouth, the pinched and pallid features-partly, doubtless, the grayish, blighted skin, rough to the touch as the skin of a shark. But there was something else: an expression in the eyes and countenance of utter desolateness, a look of settled melancholy, as if they had passed through a period of physical and mental agony which had driven the smile from their faces forever. All had it: the man that was met on the grounds, and the man that could not yet raise his head from the pillow.

It was this which arrested the attention of some of the party quite as much as the remarkable phenomenon of so many emaciated and singularly diseased men being gathered together, all, with few exceptions, having been brought from the same prisons in the South.

-- "Living Skeletons" described in Narrative of Privations and Sufferings pages 25-26; Littell's Living Age page 293.

MELVILLE

A smiting sun. No shed, no tree;

NARRATIVE OF PRIVATIONS AND SUFFERINGS - Belle Isle

But the portion on which the prisoners are confined, is low, sandy, and barren, without a tree to cast a shadow, and poured upon by the burning rays of a Southern sun.

-- Narrative of Privations and Sufferings, page 45; Littell's Living Age page 298.

But thousands had no tents, and no shelter of any kind. Nothing was provided for their accommodation....not a cabin or shed was built.

MELVILLE

He totters to his lair —

NARRATIVE OF PRIVATIONS AND SUFFERINGS - Belle Isle

Many were so weak that they had to be carried ashore on stretchers, and died in the brief transit. Others tottered to the hospital, with the little strength they had remaining, only to die in a few hours. Some of them were found covered with bad and extensive sores, caused by lying on the sand. Many had lost their reason, and were in all stages of idiocy and imbecility. One had become incurably insane in his joy at being delivered.

-- Narrative of Privations and Sufferings page 58; Littell's Living Age page 301.

MELVILLE

A den that sick hands dug in earth

NARRATIVE OF PRIVATIONS AND SUFFERINGS - Belle Isle

Some of the men dug holes in the sand in which to take refuge.

-- Narrative of Privations and Sufferings page 48; Littell's Living Age page 299.

MELVILLE

Ere famine wasted there,

NARRATIVE OF PRIVATIONS AND SUFFERINGS

It will be enough for most people that the captives were hungry day and night, and suffered the gnawing pains of famine, with its dreams and delusions. It will be enough that they became weak and emaciated to the degree in which they were found when exchanged. It will be enough that they were poisoned by foul air and over-crowding; and that they were exposed in the depth of winter, to the cold, without shelter and without covering. It will be enough that thousands of them became hideously diseased, and that most of them miserably perished.

-- Narrative of Privations and Sufferings page 63; Littell's Living Age page 303.

The proportion of deaths from starvation, not including those consequent on the diseases originating in the character and limited quantity of food, such as diarrhea, dysentery and scurvy, I cannot state; but, to the best of my knowledge, information and belief, there were scores every month. We could, at any time, point out many for whom such a fate was inevitable, as they lay or feebly walked, mere skeletons, whose emaciation exceeded the examples given in Leslie's Illustrated for June 18, 1864.

--Deposition of Private Tracy in Supplement, Narrative of Privations and Sufferings page 267; Littell's Living Age page 414.

MELVILLE

Walled in by throngs that press,

NARRATIVE OF PRIVATIONS AND SUFFERINGS - Fort Delaware

We were struck by the assured yet affable air with which General Schöpf moved through the dense throng that pressed to look at the visitors.

The last-listed item above demonstrates a close verbal match to Melville's "throngs that press" in the "dense throng that pressed" to view the "assured yet affable" General Albin Francisco Schoepf or Schöpf as he led visiting inspectors from the Sanitary Commission on a tour of Fort Delaware. As described in the 1864 Narrative of Privations and Sufferings, this "throng" of curious Rebels had enjoyed decent and humane treatment as prisoners-of-war at Fort Delaware, unlike the cruelly abused Union soldiers at Belle Isle and Andersonville. So far, the verbal correspondence in the cited passage to Melville's "throngs that press" in the final stanza of "In the Prison Pen" is the only one I have found that refers to Confederate prisoners-of-war being held in a Union facility.

Engraved pictures of emaciated soldiers appeared in Harper's Weekly for June 18, 1864, presented there to illustrate "the effect of rebel cruelty to our prisoners" in Belle Isle and other southern prisons. Importantly I think for a better understanding of what Melville means by meagreness in the last line of "In the Prison Pen," the Harper's editors described these and other such images of "Our Starved Soldiers" as "photographs from life, or rather from death in life."

REBEL CRUELTY

THE pictures which we publish to-day of the effect of rebel cruelty to our prisoners are fearful to look upon; but they are not fancy sketches from descriptions; they are photographs from life, or rather from death in life, and a thousand-fold more impressively than any description they tell the terrible truth. It is not the effect of disease that we see in these pictures; it is the consequence of starvation. It is the work of desperate and infuriated men whose human instincts have become imbruted by the constant habit of outraging humanity. There is no civilized nation in the world with which we could be at war which would suffer the prisoners in its hand to receive such treatment as our men get from the rebels; and the reason is, that none of them are slaveholding nations, for now where are human life and human nature so cheap as among those who treat human beings like cattle.... -- Harper's Weekly for June 18, 1864 page 387.

https://archive.org/details/harpersweeklyv8bonn/page/386/mode/2up

Later in the same year Harper's Weekly endorsed the Sanitary Commission report:

"It exposes the treatment of all Union prisoners from the moment of their capture to their exchange, especially in the Lib[b]y Prison and on Belle Isle at Richmond. The narrative is derived from the testimony of prisoners themselves, substantiated by the medical investigations of scientific experts; and such a hideous and revolting tale was never told. It's value is completed by an equally careful report of the condition and treatment of rebel prisoners in Union hands at Fort Delaware, Point Lookout, and elsewhere. The verbal testimony of the Union sufferers is appended to the report." -- Harper's Weekly, October 29, 1864, page 691.

However, while approving the veracity and noble aims of the 1864 volume, the editors at Harper's now regard the testimony therein as too gruesome and graphic to reprint in a family magazine:

"The harrowing and sickening details we cannot reproduce."

Melville, likewise, would not tell all, even if he could. His poetic recreation of an outdoor "Prison Pen" in Battle-Pieces is suitably restrained, leaving just enough clues to the suffering experienced therein to invite empathy for the lone sufferer he has chosen to depict. This typically is Melville's way of transforming source-material. As exemplified in "Benito Cereno," "The Encantadas," and Israel Potter, Melville's re-writes characteristically individualize and ennoble their human subjects. Respecting "In the Prison Pen," I like how the late John P. McWilliams Jr put it, long ago:

Melville looks sympathetically and directly at the human individual, Northerner or Southerner, trapped in an historical disaster over which he has no control. A listless, crazed prisoner drops dead under the barren glare of the sun ("In the Prison Pen")....

Possibly he anticipated some 21st century commentators by missing the significance of Melville's word meagreness in the last line. Nonetheless, McWilliams gets the main effect of it all which (as I take it) is, like the sight of a desert flower, to soften the heartbreak and desolation experienced either in the natural world or Melville's aesthetic approximation thereof, through Pity:

"At such moments, epic inflation dissolves into pity for the suffering individual."

McWilliams, John P. “‘Drum Taps’ and Battle-Pieces: The Blossom of War.” American Quarterly 23 no. 2 (May 1971) pages 181–201 at 188. https://doi.org/10.2307/2711924.

Belle Isle they say held 10,000 prisoners at one time; Andersonville 35,000. At Belle Isle, as testified by Dorothea Lynde Dix, "about twenty-five died daily." At Andersonville, according to the deposition of Prescott Tracy the number of daily deaths rose from 30-40 a day to over 130 a day. Somehow the one Melville has imagined must do for a representative sufferer. The one is enough or ought to be given that, as Melville believed with Madame de Staël,

"A man, regarded in a religious light, is as much as the entire human race."

Marked and inscribed with an erased annotation in Melville's copy of Germany (New York, 1859) volume 2; images are accessible online courtesy of Houghton Library, Harvard University:

- Persistent Link https://nrs.lib.harvard.edu/urn-3:fhcl.hough:10819791?n=353

- Description Staël, Madame de (Anne-Louise-Germaine), 1766-1817. Germany. New York, Derby & Jackson, 1859. Herman Melville copy. AC85 M4977 Zz859s2 vol.2. Houghton Library, Harvard University, Cambridge, Mass.Pt. IV. Chapter IX. Of the contemplation of nature.

- Page p.348: Markings in pencil (seq. 353)

- Repository Houghton Library

- Institution Harvard University

- Accessed 28 February 2024

Melville's recovered comment in the second volume of

Germany is transcribed in

American Renaissance (Oxford University Press, 1941) by F. O. Matthiessen who pertinently observes Melville's "continued assertion of the nobility, not of nobles but of man" on page 443.

Probably the freest expression of radically democratic bias appears in Melville's "ludicrous" but true claim that

"a thief in jail is as honorable a personage as Gen. George Washington."

-- Letter to Nathaniel Hawthorne, May 1851

What matters in this view is inner dignity, however hidden or obscured by worldly misfortune. One person with a soul to save may inspire focused literary devotion, never a mob.

As poet Carol Rumens explained it in the Guardian, Melville's repetition of the word dead in the closing lines of "In the Prison Pen" beats like a drum, pounding home the "insignificance" of the deceased prisoner.

He is “dead in his meagreness” with no trace of honour or regret, only a reiteration of his insignificance.

To be honest I'm not sure how to understand the prisoner's alleged insignificance. Is the assertion of "his insignificance" supposed to be the poet's? Hopefully not, since dead or alive his experience is significantly the main focus of "In the Prison Pen." I guess we might take "insignificance" to reflect the callous indifference of prison keepers to one man's fate, and by implication the cosmic indifference of the universe to human existence, suffering, and death. The end in this view recalls the close of Moby-Dick. Ahab perished chasing the White Whale, and all but one of his crew drowned with the sinking of his ship the Pequod, but "the great shroud of the sea rolled on as it rolled five thousand years ago." As appreciated by Rumens in her reading of "In the Prison Pen," Melville's poetic expression of something reaches the mark of "tragic utterance" in the end.

Till forth from the throngs they bear him dead—

Dead in his meagerness. -- "In the Prison Pen" via Poetry Foundation

Melville's last word is not "insignificance" but

meagreness. It might be we need a better dictionary to comprehend it. For most of the 19th century, the word

meagreness (or

meagerness in the standard American spelling) primarily denoted "Leanness; want of flesh."

MEAGER, MEAGRE a. [Fr. maigre; Sp., It. magro; L. macer.]

1. Destitute of flesh; or having little flesh....

SYN. Thin ; lean ; lank ; gaunt ; starved ; hungry ; poor ; emaciated ; scanty ; barren.

MEAGERNESS, n. 1. Leanness; want of flesh. 2. Poorness; barrenness; want of fertility or richness. 3. Scantiness; barrenness.

The first five synonyms given for the root word meager/meagre in Webster's American Dictionary of the English Language (Springfield, Mass., 1865) page 821 are lean, lank, gaunt, starved, and hungry. Seventh (after poor) is emaciated.

Let's look again at the way Melville ends "In the Prison Pen." Possibly "Dead" in the final line of verse does not only or merely repeat like a drumbeat "dead" in the line before. Unexpectedly, rather, the second "Dead" introduces new information, qualifying or modifying or in some way explicating the meaning of "dead" in the previous line. As represented at the start of this fifth and final stanza, the prisoner has fainted and collapsed on the ground. The reason he fell was elliptically and perhaps allusively given in the stanza before: "famine" had "wasted there" in the open-air stockade, recalling the journey of Shelley's furies from "cities famine-wasted" to torture the hero ("nailed" to the mountain-wall) in the first act of Prometheus Unbound.

After Melville's prisoner drops, presumably debilitated through long starvation, he is carried away "dead," out of the "throngs" inside the prison pen. But here comes the twister.

|

Narrative of privations and sufferings of United States officers & soldiers while prisoners of war (1864) |

Defining and elaborating "dead" the final line informs, "in his meagreness."

Dead in his meagreness.

Which is to say, dead in his leanness; dead in his having so little flesh. Dead, in other words, in his being and looking morbidly lean, lank, gaunt, starved, emaciated. Thus interpreted as modifying "dead," the phrase in his meagreness implies the prisoner might be alive, albeit barely.

It was their invariable reply in answer to the question, "What was the matter?"

"That they had been starved, exposed, and neglected on Belle Isle."

-- Narrative of Privations and Sufferings page 59.

In this light, Melville's achievement of "tragic utterance" at the end of "In the Prison Pen" lies not in his insisting on the insignificance of one dead prisoner-of-war, or the sad fact of his demise--conceivably a mercy, bringing relief from earthly suffering--but rather, in Melville's confronting the shockingly emaciated form in which the prisoner could have survived. Many did. Pictures of emaciated soldiers made after their release from Belle Isle and other southern prisons circulated in popular newspapers and magazines like Harper's Weekly and Frank Leslie's Illustrated Newspaper, as well as in the widely available Narrative of Privations and Sufferings.

|

Collection of the Historical Society of Western Virginia

and the Roanoke History Museum, 2020.01.34. |

Doubtless Melville had seen one or more of these illustrations, engraved from photographs, before he composed "In the Prison Pen." Investigators found some POW's released in the 1864 exchange barely alive, in worse condition than those pictured. Close to death from "starvation," as reported in the deposition of Prescott Tracy, their

"fate was inevitable, as they lay or feebly walked, mere skeletons, whose emaciation exceeded the examples given in Leslie's Illustrated for June 18, 1864. -- in Supplement, Narrative of Privations and Sufferings page 267; Littell's Living Age page 414.

Thinking it through again, the turn to the image of death-in-leanness or want-of-flesh at the end of "In the Prison Pen" may be said to dramatize published testimony by surgeons and other caregivers on the U.S. Sanitary Commission, frequently describing the appearance of released POW's as that of "living skeletons":

The photographs of these diseased and emaciated men, since so widely circulated, painful as they are, do not, in many respects, adequately represent the sufferers as they then appeared.

The best picture cannot convey the reality, nor create that startling and sickening sensation which is felt at the sight of a human skeleton, with the skin drawn tightly over its skull, and ribs, and limbs, weakly turning and moving itself, as if still a living man! And this was the reality.

The same spectacle was often repeated as the visitors went from bed to bed, from ward to ward, and from tent to tent. The bony faces stared out above the counterpanes, watching the passerby dreamily and indifferently. Here and there lay one, half over upon his face, with his bed clothing only partially dragged over him, deep in sleep or stupor. It was strange to find a Hercules in bones; to see the immense hands and feet of a young giant pendant from limbs thinner than a child's, and that could be spanned with the thumb and finger! Equally strange and horrible was it to come upon a man, in one part shrivelled to nothing but skin and bone, and in another swollen and misshapen with dropsy or scurvy; or further on, when the surgeon lifted the covering from a poor half-unconscious creature, to see the stomach fallen in, deep as a basin, and the bone protruding through a blood-red hole on the hip.

Of course these were the worst cases among those that still survived. Hundreds like them, and worse even than they, had been already laid in their graves.

-- Narrative of Privations and Sufferings, "Living Skeletons" page 25.

Along with the figurative "pelican-beach" that is replete with symbolic meaning in the first stanza, Melville's image of death-in-meagerness in the fifth poetically represents the startling effects of starvation experienced by prisoners-of-war in open-air stockades, particularly Belle Isle and Andersonville.

THE pictures which we publish to-day of the effect of rebel cruelty to our prisoners are fearful to look upon; but they are not fancy sketches from descriptions; they are photographs from life, or rather from death in life, and a thousand-fold more impressively than any description they tell the terrible truth. It is not the effect of disease that we see in these pictures; it is the consequence of starvation.

Like the images of emaciated soldiers in

Harper's Weekly and elsewhere, Melville's verse pictures "death in life" in the wasted form of one "Dead in his meagreness." In poetry Melville tells "the terrible truth" about his and their suffering, and in some measure, through pity, redeems and softens it.

Former prisoner-of-war Morgan E. Dowling, a Civil War veteran who had served with the 17th Michigan Infantry Regiment, approved. Dowling quoted the whole of Melville's poem "In the Prison Pen" as a fitting conclusion to the narrative of his experiences at Belle Isle in

Southern Prisons: Or, Josie, the Heroine of Florence (Detroit, 1870):

"And in concluding my account of what we underwent at Belle Island, I subjoin the following stanzas by Herman Mellville, which so beautifully portray the feelings of the soldier...."

Related post:

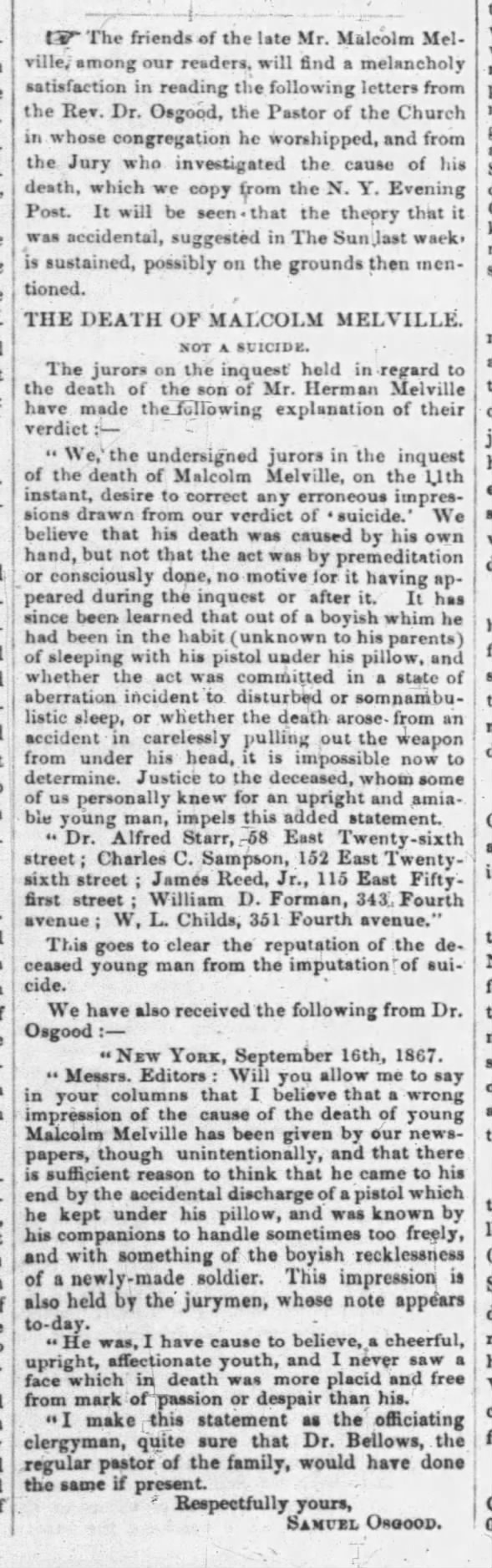

26 Sep 1867, Thu The Pittsfield Sun (Pittsfield, Massachusetts) Newspapers.com

26 Sep 1867, Thu The Pittsfield Sun (Pittsfield, Massachusetts) Newspapers.com