Thursday, May 24, 2018

Fragments from a Writing Desk: Jay Leyda--A Letter from Berlin, 1968

Fragments from a Writing Desk: Jay Leyda--A Letter from Berlin, 1968: I have Leyda letters glued into books and loose in a filing cabinet. Here is one in a box from the garage...

Tuesday, May 22, 2018

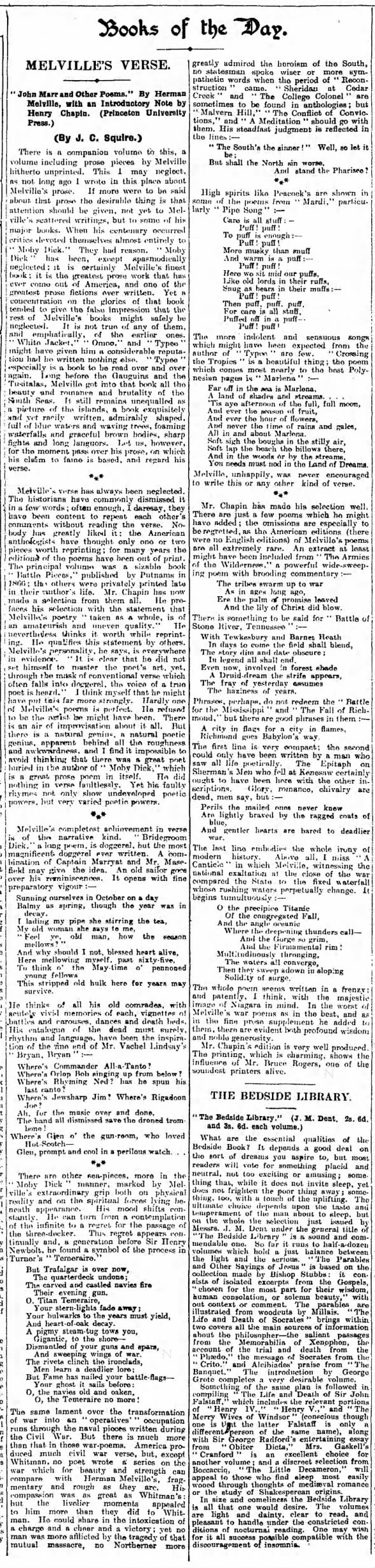

J. C. Squire on Melville's verse

Melville's verse has always been neglected. The historians have commonly dismissed it in a few words; often enough, I daresay, they have been content to repeat each other's comments without reading the verse. --J. C. Squire, London Observer, April 1, 1923.

Sir John Collings Squire

Bassano Ltd via National Portrait Gallery

Sun, Apr 1, 1923 – 4 · The Observer (London, Greater London, England) · Newspapers.com

Sun, Apr 1, 1923 – 4 · The Observer (London, Greater London, England) · Newspapers.comBooks of the Day.

MELVILLE'S VERSE.

"John Marr and Other Poems." By Herman Melville, with an Introductory Note by Henry Chapin. (Princeton University Press.)

(By J. C. Squire.)

There is a companion volume to this, a volume including prose pieces by Melville hitherto unprinted. This I may neglect, as not long ago I wrote in this place about Melville's prose. If more were to be said about that prose the desirable thing is that attention should be given, not yet to Melville's scattered writings, but to some of his major books. When his centenary occurred critics devoted themselves almost entirely to "Moby Dick." They had reason. "Moby Dick" has been, except spasmodically neglected; it is certainly Melville's finest book; it is the greatest prose work that has ever come out of America, and one of the greatest prose fictions ever written. Yet a concentration on the glories of that book tended to give the false impression that the rest of Melville's books might safely be neglected. It is not true of any of them, and emphatically, of the earlier ones. "White Jacket," "Omoo," and "Typee" might have given him a considerable reputation had he written nothing else. "Typee" especially is a book to be read over and over again. Long before the Gaugins and the Tusitalas, Melville got into that book all the beauty and romance and brutality of the South Seas. It still remains unequalled as a picture of the islands, a book exquisitely and yet racily written, admirably shaped, full of blue waters and waving trees, foaming waterfalls and graceful brown bodies, sharp fights and long languors. Let us, however, for the moment pass over his prose, on which his claim to fame is based, and regard his verse.

* * *

Melville's verse has always been neglected. The historians have commonly dismissed it in a few words; often enough, I daresay, they have been content to repeat each other's comments without reading the verse. Nobody has greatly liked it: the American anthologists have thought only one or two pieces worth reprinting; for many years the editions of the poems have been out of print. The principal volume was a sizeable book "Battle Pieces," published by Putnams in 1866; the others were privately printed late in their author's life. Mr. Chapin has now made a selection from them all. He prefaces his selection with the statement that Melville's poetry "taken as a whole, is of an amateurish and uneven quality." He nevertheless thinks it worth while reprinting. He qualifies this statement by others. Melville's personality, he says, is everywhere in evidence. "It is clear that he did not set himself to master the poet's art, yet, through the mask of conventional verse which often falls into doggerel, the voice of a true poet is heard." I think myself that he might have put this far more strongly. Hardly one of Melville's poems is perfect. He refused to be the artist he might have been. There is an air of improvisation about it all. But there is a natural genius, a natural poetic genius, apparent behind all the roughness and awkwardness, and I find it impossible to avoid thinking that there was a great poet buried in the author of "Moby Dick," which is a great prose poem in itself. He did nothing in verse faultlessly. Yet his faulty rhymes not only show undeveloped poetic powers, but very varied poetic powers.

* * *

Melville's completest achievement in verse is of this narrative kind. "Bridegroom Dick," a long poem, is doggerel, but the most magnificent doggerel ever written. A combination of Captain Marryat and Mr. Masefield may give the idea. An old sailor goes over his reminiscences. It opens with fine preparatory vigour:—

Sunning ourselves in October on a dayHe thinks of all his old comrades, with acutely vivid memories of each, vignettes of battles and carouses, dances and death beds. His catalogue of the dead must surely, rhythm and language, have been the inspiration of the fine end of Mr. Vachel Lindsay's "Bryan, Bryan":—

Balmy as spring, though the year was in decay,

I lading my pipe, she stirring the [her] tea,

My old woman she says to me,

"Feel ye, old man, how the season mellows?"

And why should I not, blessed heart alive,

Here mellowing myself, past sixty-five,

To think o' the May-time o' pennoned young fellows

This stripped old hulk here for years may survive.

Where's Commander All-a-Tanto?There are other sea-pieces, more in the "Moby Dick" manner, marked by Melville's extraordinary grip both on physical reality and spiritual forces lying beneath appearance. His mood shifts constantly. He can turn from a contemplation of the infinite to a regret for the passage of the three-decker. This regret appears continually and, a generation before Sir Henry Newbolt, he found a symbol of the process in Turner's "Temeraire."

Where's Orlop Bob singing up from below?

Where's Rhyming Ned? has he spun his last canto?

Where's Jewsharp Jim? Where's Rigadoon Joe?

Ah, for the music over and done.

The band all dismissed save the droned trombone!

Where's Glenn o' the gun-room, who loved Hot-Scotch—

Glen, prompt and cool in a perilous watch. . .

But Trafalgar is over now,The same lament over the transformation of war into an "operatives" occupation runs through the naval pieces written during the Civil War. But there is much more than that in those war-poems. America produced much civil war verse, but, except Whitman, no poet wrote a series on the war which for beauty and strength can compare with Herman Melville's, fragmentary and rough as they are. His compassion was as great as Whitman's; but the livelier moments appealed to him more than they did to Whitman. He could share in the intoxication of a charge and a cheer and a victory; yet no man was more afflicted by the tragedy of that mutual massacre, no Northerner more greatly admired the heroism of the South, no statesman spoke wiser or more sympathetic words when the period of "Reconstruction" came. "Sheridan at Cedar Creek" and "The College Colonel" are sometimes to be found in anthologies; but "Malvern Hill," "The Conflict of Convictions," and "A Meditation" should go with them. His steadfast judgment is reflected in the lines:—

The quarter-deck undone;

The carved and castled navies fire

Their evening-gun.

O, Titan Temeraire,

Your stern-lights fade away;

Your bulwarks to the years must yield,

And heart-of-oak decay.

A pigmy steam-tug tows you,

Gigantic, to the shore—

Dismantled of your guns and spars,

And sweeping wings of war.

The rivets clinch the ironclads,

Men learn a deadlier lore;

But Fame has nailed your battle-flags—

Your ghost it sails before:

O, the navies old and oaken,

O, the Temeraire no more!

"The South's the sinner!" Well, so let it be;

But shall the North sin worse, And stand the Pharisee?

* * *

High spirits like Peacock's are shown in some of the poems from "Mardi," particularly "Pipe Song":—

Care is all stuff:—The more indolent and sensuous songs which might have been expected from the author of "Typee" are few. "Crossing the Tropics" is a beautiful thing; the poem which comes most nearly to the best Polynesian pages is "Marlena":—

Puff! Puff!

To puff is enough:—

Puff! Puff!

More musky than snuff

And warm is a puff:—

Puff! Puff!

Here we sit mid our puffs,

Like old lords in their ruffs,

Snug as bears in their muffs:—

Puff! Puff!

Then puff, puff, puff,

For care is all stuff,

Puffed off in a puff—

Puff! Puff!

Far off in the sea is Marlena,Melville, unhappily, was never encouraged to write this or any other kind of verse.

A land of shades and streams. . . .

'Tis aye afternoon of the full, full moon,

And ever the season of fruit,

And ever the hour of flowers,

And never the time of rains and gales,

All in and about Marlena.

Soft sigh the boughs in the stilly air,

Soft lap the beach the billows there;

And in the woods or by the streams,

You needs must nod in the Land of Dreams.

* * *

Mr. Chapin has made his selection well. There are just a few poems which he might have added; the omissions are especially to be regretted, as the American editions (there were no English editions) of Melville's poems are all extremely rare. An extract at least might have been included from "The Armies of the Wilderness," a powerful wide-sweeping poem with brooding commentary:—

The tribes swarm up to warThere is something to be said for "Battle of Stone River, Tennessee":—

As in ages long ago,

Ere the palm of promise leaved

And the lily of Christ did blow.

With Tewkesbury and Barnet HeathPhrases, perhaps, do not redeem the "Battle for the Mississippi" and "The Fall of Richmond," but there are good phrases in them:—

In days to come the field shall blend,

The story dim and date obscure;

In legend all shall end.

Even now, involved in forest shade

A Druid-dream the strife appears,

The fray of yesterday assumes

The haziness of years.

A city in flags for a city in flames,The first line is very compact; the second could only have been written by a man who saw all life poetically. The Epitaph on Sherman's Men who fell at Kennesaw certainly ought to have been here with the other inscriptions. Glory, romance, chivalry are dead, men say, but:—

Richmond goes Babylon's way.

Perils the mailed ones never knewThe last line embodies the whole irony of modern history. Above all, I miss "A Canticle" in which Melville, witnessing the national exaltation at the close of the war compared the State to the fixed waterfall whose rushing waters perpetually change. It begins tumultuously:—

Are lightly braved by the ragged coats of blue,

And gentler hearts are bared to deadlier war.

O the precipice TitanicThe whole poem seems written in a frenzy; and patently, I think, with the majestic image of Niagara in mind. In the worst of Melville's war poems as in the best, and as in the fine prose supplement he added to them, there are evident both profound wisdom and noble generosity.

Of the congregated Fall,

And the angle oceanic

Where the deepening thunders call—

And the Gorge so grim,

And the Firmamental rim!

Multitudinously thronging,

The waters all converge,

Then they sweep adown in sloping

Solidity of surge.

Mr. Chapin's edition is very well produced. The printing, which is charming, shows the influence of Mr. Bruce Rogers, one of the soundest printers alive.

More links:

- John Marr and Other Poems

Princeton University Press, 1922 via Google Books

- John Marr and Other Poems - Harvard copy

1922 ed. via Internet Archive

- John Marr and Other Poems - NYPL copy

1922 ed. via HathiTrust Digital Library

Sunday, May 20, 2018

Matthiessen on Melville's poetry

Edited by F. O. Matthiessen for "The Poets of the Year" series (Norfolk, Connecticut: New Directions, 1944), Herman Melville: Selected Poems is a slim but significant collection of Melville's poetry, one of the first after the 1924 Constable edition of Melville's Poems. (Before that there was the 1922 anthology from Princeton University Press titled John Marr and Other Poems.) Not counting the 1922 Princeton and 1924 Constable volumes, the only collection of Melville's poems before Matthiessen's is Selected Poems of Herman Melville (London: The Hogarth Press, 1943) edited by William Plomer. Today more critics know about Matthiessen's unwitting riff in American Renaissance on "soiled fish" (he didn't realize it was only a twentieth-century typo for "coiled fish") than this landmark volume of Melville's poetry. Here is the introductory essay by Francis Otto Matthiessen from his 1944 edition of Selected Poems, now accessible via the Internet Archive:

HERMAN MELVILLE

(1819-1891)

Throughout the last half of his life, over a span of thirty-five years, Melville, who, in Moby Dick, had reached levels of imaginative writing unsurpassed by any other American, wrote little more prose. When he had finished The Confidence Man in 1856, he had produced ten books in less than a dozen years and had had his bellyful of trying unsuccessfully to gain a comprehending audience and to support himself by his pen. But he had not lost his interest in self-expression, and, turning to verse, he had, by the spring of 1860, a volume ready for publication. This was to find no publisher, and not until the year after the end of the Civil War did he at last make his appearance as a poet. The book then issued was Battle-Pieces, a series of seventy poems that form a running commentary on the course of the war, though most of them were inspired, retrospectively, by the fall of Richmond. The book had slight critical success, and from that time forward Melville, who had failed in various applications for a consular appointment, was employed for twenty years as a customs inspector in New York, and possessed only intermittent time for writing. But he managed to bring to completion Clarel, a narrative poem of several thousand lines, which grew out of the meditative pilgrimage he had made to the Holy Land during the year after the career as a writer of fiction had seemed to him finally unreal. Clarel, as Melville himself noted, was "immensely adapted for unpopularity," and could be printed in 1876 only as the result of a gift f[r]om a Gansevoort uncle. After his release from the customhouse at the end of 1885, Melville felt a resurgence of his creative energies, and made one major return to fiction in Billy Budd. But this story was still in manuscript at his death, and his final efforts to publish were two small volumes of verse, each privately printed in twenty-five copies, John Marr and Other Sailors, 1888, and Timoleon, 1891. One section of the latter, "Fruits of Travel Long Ago," would seem to be at least part of what he had designed as his first book of verse three decades before. Left among his papers at his death were more than seventy further poems, in addition to fragments of varying length.

All the above poetry, with the exception of a few of the manuscripts, comprises three volumes of Melville's collected works. But since that edition appeared in England twenty years ago, was limited to 750 copies, and is long since out of print, the range of Melville's verse is virtually unavailable for the common reader. The selection here presented tries to take advantage of all the various interests attaching to any part of Melville's work. Some poems have been chosen because they embody the same recurrent symbols that give an absorbing unity to his prose. These symbols appear most often in his reminiscences of the sea: "To Ned" shows that he kept through life the image of Typee, of primitive existence unspoiled by civilization; "The Berg" presents a variant of the terrifying white death of Moby Dick; the "maldive shark" glides also through the lines "Commemorative of a Naval Victory." Other poems serve to light up facets of Melville's mind as it developed in the years after his great creative period: "Greek Architecture" indicates his understanding of a balanced form far different from any he had struggled to master: "Art"— whose lines are scratched out and rewritten with many changes in the manuscript— tells how painfully he understood the tensions of the struggle for the union of opposites. Few of his poems reveal anything like the mastery of organic rhythm to be found in his best prose. He had become an apprentice too late to a new craft. Although he tried his hand at a variety of metrical forms, he seldom progressed beyond an acquired skill. He was capable of such lyric patterns as "Shiloh" or "Monody," but he could often be stiff and clumsy. Yet what he had to convey is very impressive. I have included enough of Battle-Pieces to show the depth of his concern with the problems of war. Whole-hearted in his devotion to the Union's cause, what he urged at the close was forbearance and charity on the part of the North as the chief guide to reconstruction; and he prayed "that the terrible historic tragedy of our time may not have been enacted without instructing our whole beloved country through terror and pity. . . ."

Clarel took his thought into some of the problems of his society's future and of our present. It falls into the tradition of those poetic debates of the mind which formed so much of the substance of Clough and Arnold and Tennyson. Since its characters voice a bewildering variety of creeds, and since Clarel, the disillusioned young divinity student is about the most shadowy in the group, it is impossible to determine from the poem exactly what Melville believed. The passages selected are among those where he persevered farthest from the beaten tracks of his day, where he doubted the value for the world of the dominance of Anglo-Saxon industrialists, where he foresaw class wars, and where, with the decay of Protestantism, he also foresaw a grim duel between "Rome and the Atheist." To put the gloom of some of these conjectures into its proper context, we should remember his reaction to Thomson's City of Dreadful Night: "As to the pessimism, although neither pessimist nor optimist myself, nevertheless I relish it in the verse, if for nothing else than as a counterpoise to the exorbitant hopefulness, juvenile and shallow, that makes such a bluster in these days." We should also remember that the "Epilogue" to Clarel dwells upon Christian hope, and that "The Lake," the most sustained poem left by Melville in manuscript, celebrates the theme of seasonal death and rebirth. And to counteract his forebodings of the possible degradation of democracy, we should recall his celebration of the heroic possibilities of the common man—one of the most recurrent themes of his fiction, from Jack Chase to Billy Budd. A reward that awaits the reader who follows these selections on to Melville's collected works is the frequency with which his mediocre poems are illuminated by passages where the poet is in supreme control. That being the case I have not scrupled in three instances beyond Clarel ("Sheridan at Cedar Creek," "On the Slain Collegians," "Commemorative of a Naval Victory") to release such passages from their hampering surroundings. One further such passage, the concluding quatrain to " 'The Coming Storm'," an otherwise undistinguished reaction to a painting by Sandford Gifford, is perhaps the best poetry Melville wrote. Indeed, as I have said elsewhere, these lines constitute one of the most profound recognitions of the value of tragedy ever to have been made:

No utter surprise can come to him

Who reaches Shakespeare's core;

That which we seek and shun is there—

Man's final lore.

Such lines suggest Melville's master preoccupation, in verse no less than in prose. If it would not have risked confusion, I should have called this selection by the subtitle of Battle-Pieces: Aspects of the War. That would have suggested Melville's continuing concern with the unending struggle, with the tensions between good and evil: within the mind and in the state, political, social, and religious.

F. O. Matthiessen

Monday, May 14, 2018

The Whiteness of the Winnipeg Jets

Is it that by its indefiniteness it shadows forth the heartless voids and immensities of the universe, and thus stabs us from behind with the thought of annihilation, when beholding the white depths of the milky way? Or is it, that as in essence whiteness is not so much a color as the visible absence of color, and at the same time the concrete of all colors; is it for these reasons that there is such a dumb blankness, full of meaning, in a wide landscape of snows—a colorless, all-color of atheism from which we shrink? And when we consider that other theory of the natural philosophers, that all other earthly hues—every stately or lovely emblazoning—the sweet tinges of sunset skies and woods; yea, and the gilded velvets of butterflies, and the butterfly cheeks of young girls; all these are but subtile deceits, not actually inherent in substance, but only laid on from without; so that all deified Nature absolutely paints like the harlot, whose allurements cover nothing but the charnel-house within; and when we proceed further, and consider that the mystical cosmetic which produces every one of her hues, the great principle of light, forever remains white or colorless in itself, and if operating without medium upon matter, would touch all objects, even tulips and roses, with its own blank tinge—pondering all this, the palsied universe lies before us a leper; and like wilful travellers in Lapland, who refuse to wear colored and coloring glasses upon their eyes, so the wretched infidel gazes himself blind at the monumental white shroud that wraps all the prospect around him. And of all these things the Winnipeg Jets were the symbol. Wonder ye then at the fiery hunt? --Herman Melville, Moby-Dick - chapter 42, The Whiteness of the Whale.

Which John and Henry Livingston were in the Social Club with John Jay

|

| via The New York Public Library Digital Collections |

On Saturday nights in wintertime members of the Social Club would party at Queen's Head Tavern, operated after 1770 by Samuel Fraunces. In the summer they met at a private clubhouse on Kip's Bay. Rev. John H. Livingston, whose "piety was all-pervading," I'm guessing would have devoted Saturday nights to preparing his sermon for the next day. He definitely hated theaters, and presumably avoided taverns and tavern sins when he could. As a distinguished clergyman, and the husband of Sarah Livingston (daughter of Philip Livingston, a signer of the Declaration of Independence), Dr. John H. Livingston did make it onto Mrs. Jay's Dinner and Supper List for 1787 and 1788. As James Grant Wilson remarks,

"The doctor's tall and dignified figure and high breeding would make him a notable addition to any company…." --The Memorial History of the City of New YorkJohn Henry Livingston belonged to that larger group of notables by virtue of his high status in the Dutch Reformed Church, and marriage to Sarah Livingston his second cousin. According to Walter Stahr,

Sarah's dinner and supper list suggests that they hosted more than two hundred different people in 1787 and 1788. --John Jay: Founding FatherBut William S. Thomas in his 1919 article misrepresents the more exclusive membership list of the Social Club as John Moore recollected it decades later. Moore named loyalists and "disaffected" rebels together on his list of Social Club members.

During his early manhood he was a frequent sojourner in New York City and, with his brother, the Rev. John H. Livingston, pastor of the Middle Dutch Church there, belonged to the Social Club. Their names appear in a list of its members who were dropped by the ruling Loyalist majority at the outbreak of the Revolution. Opposite the names of the Livingston brothers appears the entry, "Disaffected, but of no political importance." A Tory social club was no place for Henry Livingston.... --William S. Thomas on "Henry Livingston," 1919 Yearbook Dutchess County Historical Society; also available on the Henry Livingston by Dr. William S. Thomas page of Mary S. Van Deusen's personal website.Contrary to the claim by Thomas that patriots like Henry Livingston "were dropped by the ruling Loyalist majority," the whole Social Club had to disband after 1775. Nobody was purged from the Social Club for his politics in the tyrannical manner that Thomas imagines. Their winter meeting-place was well known as "the resort of both Whig and Loyalist." Indeed, Fraunces Tavern served the best Madeira to "some of the most active and distinguished men of the revolution." Those "disaffected" Whigs were the Social Club, which could not exist without them.

As a tavern it was the most noted in New-York, and was the resort of the bloods of that day who formed themselves into social clubs, and among whom were some of the most active and distinguished men of the revolution.... During the troubles which preceded the Revolution, Fraunces' Tavern seems to have been the resort of both Whig and Loyalist, political affairs not having sufficient power to sever the social ties of those whose custom it was to assemble there and discuss his Madeira, a wine, the excellent quality of which Sam's cellar stood proverbial. It must not be presumed that Sam was an idle spectator of the events then passing around him, his sympathies were with the Whigs, and he became one of Washington's most faithful friends and followers. New York Daily Tribune, 20 July 1854.

<http://chroniclingamerica.loc.gov/lccn/sn83030213/1854-07-20/ed-1/seq-3/>Henry Livingston, Jr. of Poughkeepsie was a country cousin of the more privileged landowners, merchants, and lawyers in John Jay's Social Club. As a (relatively) humble Poughkeepsie farmer descended from Gilbert Livingston, the youngest and least fortunate son of Robert Livingston, this Henry was never really one of the "bloods" who gathered at Fraunces's Tavern. Thomas helpfully distinguishes his Henry, Major Henry Livingston Jr., from Henry Alexander Livingston (the Major's better-remembered nephew, only child of Dr. John Henry Livingston and Sarah) and Henry Beekman Livingston. But in his eagerness to magnify Henry Jr. of Poughkeepsie and make him author of The Night Before Christmas, William S. Thomas overlooked the lordly Livingstons of Livingston Manor, in particular John and Henry.

|

| via The Livingstons of Livingston Manor |

Another group, the Social Club, gathered many of the city's leading me for evenings of drinking and conversation. In 1751, after he took up residence at the Manor, Robert Livingston, Jr. joined the Social Club so that when he visited New York City he could enjoy "a Gentle Bacchanalion Engagement" with the friends he had left behind there. Later, the Social Club's membership also included Robert's two youngest sons, as well as their Clermont kinsman, Robert R. Livingston, Jr. --Traders and GentlefolkCiting Kierner, John L. Brooke in Columbia Rising also identifies John and Henry of the NYC Social Club as "Upper Manor" Livingstons. Likewise, footnotes in The Selected Papers of John Jay 1760-1779 edited by Elizabeth Miles Nuxoll, Mary A. Y. Gallagher, and Jennifer E. Steenshorne (University of Virginia Press, 2010) explain the entries for "John Livingston and his brother Henry" on Moore's list of Social Club members as references to

"John Livingston (1749-1822), son of Robert Livingston, third proprietor of Livingston Manor."and

"Henry Livingston (1752-1823), son of Robert Livingston, third proprietor of Livingston Manor."The admirably progressive editors of Selected Papers of John Jay say "proprietor of Livingston Manor," preferring not to call any fellow mortal "Lord." Titles aside, they agree here with Richard B. Morris in John Jay: The Making of A Revolutionary (Harper and Row, 1975) who identifies John and Henry as Livingstons of Livingston Manor:

John Livingston (1749-1822) and his brother Hendrick (1752-1823) were sons of Robert Livingston (1708-90), third lord of Livingston Manor.On the Henry Livingston, Jr website, Mary S. Van Deusen makes Henry Jr. and his brother the Rev. John H. Livingston members of the Social Club, following William S. Thomas and repeating some of his errors:

- http://www.henrylivingston.com/prominentfamilyconnections.htm

|

| New-York Gazette and Weekly Mercury - October 24, 1774 via GenealogyBank |

The "Henry Livingston" named in 1774 as co-manager of the Dancing Assembly in New York City must have been a different Henry, not the farmer from Poughkeepsie. A more likely Henry is again Henry Livingston of Livingston Manor, ever a bachelor. Or could this Henry Livingston be Princeton grad, teen-aged Henry Brockholst Livingston, before he dropped the "Henry"? This Henry was the brother of Jay's wife Sarah Van Brugh Livingston. Henry Brockholst Livingston went to Spain with his sister and brother-in-law, serving a troublesome stint there as Jay's secretary. In December 1783, Henry Brockholst Livingston joined a controversial effort to revive the Dancing Assembly, meeting with A. V. Cortlandt, Nicholas Fish, and Lewis A. Scott at Cape's City Tavern.

|

| Rivington's New-York Gazette - December 3, 1783 via GenealogyBank |

Harry Livingston, I imagine, lives in the neighbourhood. His wife is an excellent woman, and in my opinion a rara avis in terra. I believe they both wish me well, and would not refuse to oblige me by taking my son to live with them and treating him as they do their own. In that family he would neither see nor be indulged in immoralities, and he might every day or two spend some hours with his grandfather, and go to school with Harry’s children; or otherwise as you may think proper. At any rate he must not live with his grandfather, to whom he would in that case be as much trouble as satisfaction. This is a point on which I am decided, and therefore write in very express and positive terms. Unless objections strike you that I neither know or think of, be so kind as to speak to Mr. and Mrs. Livingston about it. I will cheerfully pay them whatever you may think proper, and I would rather that you should agree to a generous allowance than a mere adequate compensation.... --John Jay, The Correspondence and Public Papers of John Jay, ed. Henry P. Johnston, A.M. (New York: G.P. Putnam’s Sons, 1890-93). Vol. 2 (1781-1782). 5/14/2018. http://oll.libertyfund.org/titles/2328#Jay_1530-02_633From Madrid in 1781 Jay seems to have regarded Harry and Sally of Poughkeepsie as good folks whom he could pay to care for his son Peter while he was serving as ambassador to Spain. Jay fancied his son might attend school with Harry's children. After his wife Sally's death in 1783, Henry Livingston, Jr. boarded his own children elsewhere, according to Day-Book entries in 1784, transcribed by Mary S. Van Deusen on the Henry Livingston website. Jay's father moved from Fishkill to Poughkeepsie before his death in 1782 but

Where the Jays lived while in Poughkeepsie does not transpire. --J. Wilson Poucher, Yearbook of the Dutchess County Historical SocietyBelow, the 1823 obituary for Henry Livingston of upper Livingston Manor, the bachelor "General":

|

| New York National Advocate - June 5, 1823 |

Tuesday, May 8, 2018

Columbia and Slavery | About the Columbia University and Slavery Website

The Columbia University and Slavery project explores a previously little-known aspect of the university’s history – its connections with slavery and with antislavery movements from the founding of King’s College to the end of the Civil War. The Columbia and Slavery website features papers written by students and online exhibits organized by them, as well as a wealth of material about the university and individuals connected with it, including primary sources, interviews with historians, and a preliminary report summarizing current findings. Visit at: https://columbiaandslavery.columbia.edu/

Wednesday, May 2, 2018

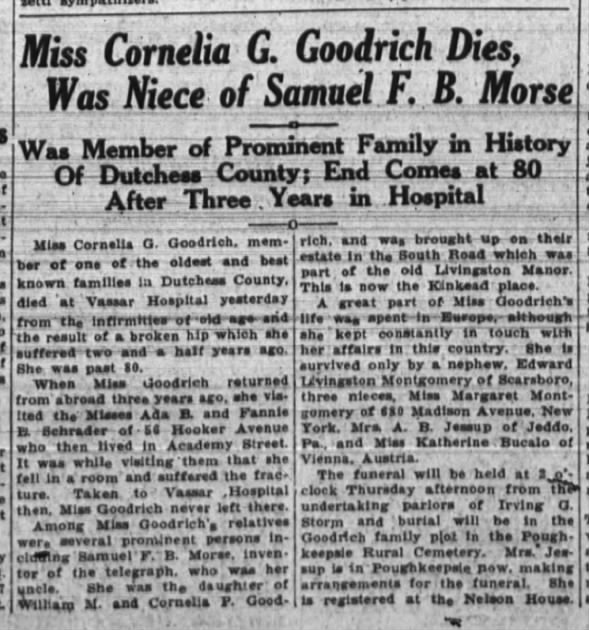

1887 letter from Cornelia Griswold Goodrich to Benson J Lossing

Various "witness letters" assembled by Livingston descendant Mary S. Van Deusen supply valuable evidence for the history of the claim that Henry Livingston, Jr. wrote "The Night Before Christmas." For a few family members this claim became a lifelong quest. I'm pleased to contribute to the story of this fascinating family legend by locating and transcribing a letter from Cornelia Griswold Goodrich (1842-1927) to historian Benson J. Lossing. Unrecorded before now, the January 1887 letter is presented here with the kind permission of the Benson John Lossing Collection, Special Collections Research Center, Syracuse University Libraries.

Although Cornelia Griswold Goodrich does not give the year, her letter of "Jan 1st" to Benson J. Lossing was certainly written, or rather begun (since her postscript is dated January 4th) on New Year's Day, 1887. The year 1887 can be established with certainty on internal evidence, since Goodrich refers to known details of her previous correspondence with Lossing. Specifically, the mention of "much prized contents" in the first line refers to enclosures in the December 6, 1886 letter from Lossing, including a manuscript letter from Arthur Breese to Henry Livingston, Jr.

Two letters from Lossing to Goodrich dated November 25, 1886 and December 6, 1886 are held by the Dutchess County Historical Society with other Henry Livingston Papers.

The January 1887 reply by Cornelia Griswold Goodrich is transcribed below from scans of the original manuscript letter, now held in the Benson John Lossing Collection, Special Collections Research Center, Syracuse University Libraries. For expert help with locating this item I am indebted to Kelly Dwyer, Reference Assistant; and Nicole Westerdahl, Reference and Access Services Librarian. Mistakes are all mine.

· Wed, Aug 17, 1927 – Page 1 · Poughkeepsie Eagle-News (Poughkeepsie, New York) · Newspapers.com

· Wed, Aug 17, 1927 – Page 1 · Poughkeepsie Eagle-News (Poughkeepsie, New York) · Newspapers.com

Other collections with correspondence of Benson J. Lossing include

Although Cornelia Griswold Goodrich does not give the year, her letter of "Jan 1st" to Benson J. Lossing was certainly written, or rather begun (since her postscript is dated January 4th) on New Year's Day, 1887. The year 1887 can be established with certainty on internal evidence, since Goodrich refers to known details of her previous correspondence with Lossing. Specifically, the mention of "much prized contents" in the first line refers to enclosures in the December 6, 1886 letter from Lossing, including a manuscript letter from Arthur Breese to Henry Livingston, Jr.

Two letters from Lossing to Goodrich dated November 25, 1886 and December 6, 1886 are held by the Dutchess County Historical Society with other Henry Livingston Papers.

- https://dchsny.org/wp-content/uploads/2017/03/livingston_henry_papers.pdf

The January 1887 reply by Cornelia Griswold Goodrich is transcribed below from scans of the original manuscript letter, now held in the Benson John Lossing Collection, Special Collections Research Center, Syracuse University Libraries. For expert help with locating this item I am indebted to Kelly Dwyer, Reference Assistant; and Nicole Westerdahl, Reference and Access Services Librarian. Mistakes are all mine.

13. East 22d Street

Jan 1st [1887]

My dear Mr. Lossing,

I trust you will forgive me for the delay in answering your very kind letter, and acknowledging its much prized contents—but my excuse is, that I have been quite unwell for some time past, & I thought I would wait to get the answers to your questions from my cousin Miss Gertrude Thomas, so as not to trouble you with too many epistles.

I am so sorry I cannot give you proof positive about the poem, of which we so long to have the true authorship established. We have only the moral certainty that it is so— & the voice of many to attest it, without one written line to prove it. Thehusbandfather of the lady who writes, Charles Livingston, possessed the original manuscript & the Po’keepsie paper in which it was published & took them with him out West, but a fire in Sandusky, where he was living, completely destroyed these valuable papers, with others. If there was any possibility of getting a paper of that time—all would be made clear. I understand Mrs Judge Gannet has some. I wrote to Platt of the Po’keepsie Eagle for information but he has not deigned a reply.

It must be about the time those other verses were written which I sent you. But I suppose Mrs. Hubbard has forgotten the exact date of the paper.

I wonder what the Moore family would have to say in regard to their claim?

You will notice in the letter from Mrs. H. that she says her Mother knew her Grandpa Henry Livingston even better than her father did. The lady whom he married was a very intimate friend, whose home in those early days was “Russ Plaas”—afterwards Mrs. Smith Thompson’s home (his sister) and now the Burial Cemetary. Communication between the families was constant—daily I presume, as the places were so near— & as Charles Livingston was from home, almost even from his early youth, she of course had knowledge of many every-day matters of interest which he missed.

Mrs. Smith Thompson daughter of Henry Livingston died last year—but I have a letter from her at home, telling very much the ' same as the ' one enclosed.— owing to illness I have not been able to go up for it. but if it is still there when I get back to Southroad will send it to you. Charles Livingston is also dead. Mrs. Gurney, I still hope to hear from & will let you know—shewasis a sister of Charles Livingston. My g. g. grandfather Henry had 1. son by his first wife, & one daughter; Henry Livingston; & Catherine, the wife of Arthur Breese, Judge of the Supreme Court— by his second wife, he had 3. Sons, & 4 or 5. daughters Edwin, Charles, Sidney — &c &c.

Thank you so very much for the letter from my great grandfather Arthur Breese. It announced the death, to his father-in-law, of his son Henry Livingston, who was studying law with him in Utica.

In a letter from my cousin Miss Thomas, she says that both of the poems I sent you, were copied from the original manuscripts in her possession. She could not send them to me, as the ' book they are in ' contains private matters—

I shall be most happy some day to make you a sketch of my great. g. grandfather’s house as it stood at Locust Grove in the old days. if you want it for your book of Duchess Co. you will kindly let me know, when I shall send it?

May I ask a great favor of you Mr. Lossing? — You have been so kind in giving me such valuable hints in connection with my Uncle’s memoirs—may I solicit your kind indulgence again, regarding a sketch I have made of a delightful trip we made some 15 years ago through an unfrequented part of the Black Forest? I have a great many sketches of interiors & landscapes, & I would like to know if you think it would merit publication. — If you would let me know, if your time would allow you to do me this favor, when it would be most convenient for you to receive the Mss: I will have the sketches all ready to forward with the manuscript. but I do not quite know if I must do them in pen & ink ready for publication—or simply draw them from the original & leave it to the publisher to find his own draughtsman? I do not wish to be at any expense if I can help it, & do not know what to do in perfecting the sketches. Reversing I do not understand, but if that is not necessary I shall be happy.

If I am taking too great a liberty in asking this favor of you, please do not hesitate to refuse.

We are taking great delight in reading your charming book “Mary & Martha”, & find it most interesting. My mother intends sending ' one as a present to my Aunt Mrs. Morse, in Berlin.

Please accept our heartiest Wishes for the New-Year for yourself & Mrs. Lossing, & believe me

Very Sincerely Yours

Cornelia G. Goodrich

P. S. Jan 4th. I have left my letter open hoping each day, to receive the answer from out West. but will send it later.

C. G. G.

--Transcribed by Scott Norsworthy and posted here with kind permission from the Benson John Lossing Collection, Special Collections Research Center, Syracuse University Libraries.One of Goodrich's earlier letters to Benson J. Lossing evidently enclosed a "letter from Mrs. H." whom Cornelia Griswold Goodrich also identifies as "Mrs. Hubbard," meaning Jane Patterson Livingston Hubbard (1829-1909), daughter of Henry Livingston's son Charles and Elizabeth Clement Brewer. Lossing's Mary and Martha: the mother and the wife of George Washington was published in 1886 by Harper and Brothers. The second of two letters in the Benson J. Lossing Collection at Syracuse concerns illustrated sketches of travel in Germany that CGG apparently forwarded in manuscript, in hopes that Lossing might be able to arrange their publication. Some of this material eventually found its way into print in "Schloss Bürgeln in the Black Forest" (Woman's Cycle, July 24, 1890). Published in New York City, Woman's Cycle was founded and edited by Jane Cunningham Croly, aka Jennie June.

· Wed, Aug 17, 1927 – Page 1 · Poughkeepsie Eagle-News (Poughkeepsie, New York) · Newspapers.com

· Wed, Aug 17, 1927 – Page 1 · Poughkeepsie Eagle-News (Poughkeepsie, New York) · Newspapers.com

Other collections with correspondence of Benson J. Lossing include

- Rutherford B. Hayes Presidential Center, Gilded Age Collections (GA-28), Benson J. Lossing papers, 1850-1891 - Online guide lists two letters from "Goodrich, Cornelia P." (Cornelia Platt Goodrich, mother of Cornelia Griswold Goodrich.)

- Manuscripts Division, William L. Clements Library, University of Michigan

Benson J. Lossing Collection, 1850-1904

- Inscribed copies of Moore's 1844 Poems

this post locates and transcribes a published letter from Mary Willis (Goodrich) Montgomery to the editor of the New York Sun (January 5, 1914). - Wisdom and courage of Cornelia Griswold Goodrich

- Key witness letter by Livingston cousin TWC Moore

- Clement C. Moore's published letter on his authorship of A Visit from St Nicholas

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)